Jessica Fridrich, thank you for taking the time to answer a few questions about your photography and your work as a steganographer. What a great word! Can you offer a little background on your first photographic experiences? Did they occur in the Czech Republic, or after you came to the States?

My interest in photography intensified with the emergence of digital imaging catalyzed by my first visits to the American West in 1993 and 1995. It is fair to say that I started taking pictures while hiking and ended up hiking to take pictures. Also, since I was a child I was fascinated with astronomy. I always wanted to image deep space objects but such technology was simply unavailable in the socialistic Czechoslovakia. I get easily excited today with what one can achieve with relatively inexpensive equipment.

What is your favorite camera?

The one I use, which is Canon 6D. I chose this body because it is the smallest and lightest of all full frame cameras on the market, which is important when hiking to difficult-to-reach locations. The 6D also has wonderful low light performance, which makes it great for night photography. Recently, I have been eyeing the medium format.

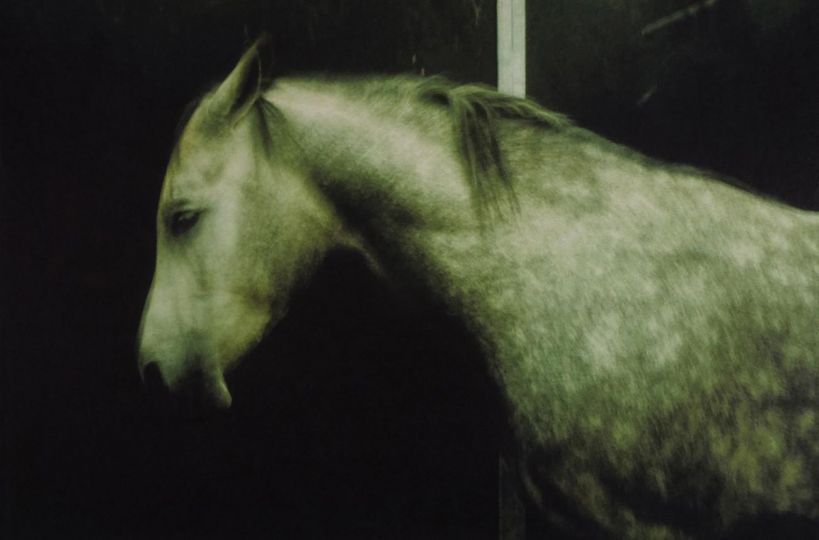

Your photographs have both a luminescent, almost transparent quality, while offering an opaque chroma that draws in the viewer seeking to find out where and how those colors come from. How do you achieve that effect?

I want to answer that it is not me but the subject and the special light that do the magic. And it is the right answer to a large degree. The Colorado Plateau is one of the most colorful places in the entire World. The sandstone is colored by minerals and chemical elements and then bleached by ground waters. Iron and manganese oxides are the two main culprits in the Paria Wilderness where I took most of the pictures from the Elusive series.

Having provided the scientific reason for the vivid colors in the rock, the other half of the job is allowing the rock to be caressed by the right light and bring those colors out in postprocessing. The special light is extremely rare and most of the time I leave without a picture and try again next time, next month, next year. There are locations I visited close to 20 times before the weather finally gave me what I was looking for.

Where do you have your C Prints printed? How did you happen to mount your images on aluminum panels?

The prints and the mounting is done by a company called Reed based in Colorado. They have been serving the fine art market for a long time and have great experience with delivering museum quality products.

In your Artist Statement, you write, “Light painting with a flashlight can be described as real-time dodging and burning similar in spirit to that which is done in a conventional darkroom during developing.” Have you spent time in a darkroom, or is all your work digital?

All my work is digital. However, the light painting is very similar to developing a conventional analog photograph. Instead of light from a magnifier, I use a flashlight.

What equipment do you take with you into the field, besides cameras, a flashlight, a tent and a tripod?

I usually bring about 4-5 lenses. Two are fast prime lenses for night shooting, Rokinon 24 mm f1.4 and Rokinon 14 mm f2.8. The wide angle is a wonderful lens for daylight photography, too. Frozen in Time was shot with it. And then 16-35 mm 2.8 II and 24-70 mm 2.8 II Canon lenses and 70-200 f4.0 telephoto. I also bring a 3 stop split density graduated filter, B+W circular polarizers, a lens cleaning kit, first aid kit, numerous spare SD cards, a spare battery for the camera and for flashlights, at least two flashlights in case one breaks. Sometimes I also bring a second tripod for the flashlight and additional light sources, such as a solar powered LED power bank and another solar powered LED light source. I also bring a GPS and a satellite beacon for emergency. When I am leaving for a day hike, together with a gallon of water, food, spare clothes, my backpack can be easily over 35 Lbs.

How did you happen upon the idea of identifying the source of a digital image?

The time when seeing was believing is long gone. With the transition to digital imaging, creating fake reality has become easier than ever. Establishing provenance and integrity of digital media is important for forensic investigators, law enforcement, and intelligence gathering. We started looking into whether one could tell which camera took a given picture more than 13 years ago when few were asking these questions and those who did not have good answers.

What is the digital fingerprint of a particular camera? Does it vary within the camera brand, or is it specific to the individual camera used to take a photograph?

The fingerprint is an intrinsic property of an imaging sensor and thus unique to each camera. Imagine that you take picture of a completely uniform scene, such as blue sky. What the camera registers though is not a completely uniform signal. There will be small differences between pixels. Most of these differences are due to various noise sources that are random and thus cannot be used for identification. One such component, however, is not random and repeats in the same or similar form from picture to picture. It is called photo-response non-uniformity abbreviated as PRNU and this is the sensor fingerprint. We developed a method for estimating this fingerprint from images and its detection in images to establish the origin of the image. It is even possible to match a printed image to a camera. It works for video, too.

In the series of 1s and 0s in a digital image, is it the variation between chips or the lens used that makes the bigger difference, or are they both critical to the process? Or neither? Am I off-base in this approach to understanding what is going on?

It is the variation between pixel values. Lens has no effect. The fingerprint is a property of the sensor.

If there is a digital fingerprint, what do you think about all cameras taking a photograph that is stored in a digital database against which all subsequent photos can be compared to identify the source, as is done with firearms?

This is certainly possible. The analogy with firearms is correct. Just like one can identify a gun barrel by scratches on the bullet casing, we can identify the camera by sensor fingerprints. In fact, some people call our technique “digital ballistics”.

What are the practical applications these days for steganography?

Steganography is the art of secret communication in which a message is hidden in an image by slightly modifying the pixel values. It is a private communication method. In some hostile countries with authoritarian regimes, use of encryption is prohibited. If the censors cannot read your messages you could be in trouble. Steganography then becomes the only way to communicate in privacy because the censors think they know what you are sending — a picture from your cellphone — when in fact the real message is hiding in the pixel values and its presence is not obvious.

Your photographs of natural phenomena capture extraordinary settings that most people will never see to appreciate, as they are created in a sort of vacuum in which you are communing with nature in a unique and presentational way. How long or short are some of these exposures?

The night photographs are usually 15-25 second exposures. You are right that it may not be easy to identify with a landscape that one has never seen or experienced. It reminds me of magic. Some people will like a magic trick because they get amazed and do not want to know how it was done. Others want to know or even know the trick but still appreciate it in a very different way because they are aware of how difficult it is to execute it. Some of my night pictures look like they were generated on a computer or at least manipulated in Photoshop. Yet, they are all carefully planned and executed single shots of real places. I plan the shots and their timing to make them look in a special way, to convey a certain mood. I once had a professional photographer telling me that the Colors of Darkness, which portrays a famous formation called the Wave, must be a composite because I could never get that light. Now that is an offense and praise in one sentence.

When you go into the field to photograph a setting, do you know where you are going, what you will be doing, where you will be placing the camera, how long an exposure and what time of day? How many hours do you spend “setting up” a shot?

Excellent question that is hard to answer. It depends. For night landscapes, I typically carefully preconceive a composition and then plan it. I need to consider the location of the Milky Way, the Moonlight, and any other sources of light. Then, there is the light painting that sometimes needs to be executed and that is very hard to do right. Sometimes, I will use Moonlight to illuminate the landscape and do not light paint. Other times, I may set up several sources of low level light with my LEDs to illuminate. Setting up the light and/or getting the light painting “in my hand” can be very elaborate. The need to light paint also limits possible compositions because I cannot light paint distant objects.

It is a lot of fun to do the planning. I use star charts, the program called The Photographer’s Ephemeris, and Google Maps to plan out shots. Sometimes, I will be planning a shot for a year. Not all, however, can be preconceived and there are always surprises. For example, the Magnetic (the shot of Delicate Arch) was the results of desperation. I was planning to shoot the arch against the backdrop of the Milky Way. It was, however, fairly cloudy with minimal sky showing through. I was almost ready to leave but did “give it a shot” literally. What I did not preconceive was that the clouds would be gently lit by the City of Moab and create a much more dramatic backdrop than a clear sky would. After all, the Milky Way did shine in between the clouds, which worked out really well as there is power in covering up beauty rather than serving it in plain view.

With daylight shots, planning is much more difficult because one never knows what kind of light you get, where the clouds and color will be. I still do have ideas in mind but try to be flexible to capitalize on sudden opportunities. Stubbornly insisting on one composition no matter what happens around me does not work for me even though sometimes this is what I have to do. As I said, it depends on many factors, such as how big the location is and whether I can get myself in time to different nearby locations. When the great light comes, it lasts for a very short time and you do not want to waste it.

When you go into the field to shoot, do you travel alone? Are you ever concerned about wildlife encounters?

I mostly travel alone. It is easier because people have different preferences on what they want to do. Even when I team up with another photographer, we usually disperse and execute our own ideas. I was once approached by a photographer at the White Pocket. He asked me what I was planning to shoot at sunset. I shared my idea with him and we ended up shooting the same formation. He submitted his shot to a competition and it ended up in the Smithsonian art museum as part of the America the Beautiful series.

The wildlife is something I need to be constantly aware of, especially at night when hiking with rattlesnakes around. I once was hiking to a location at night and I almost stepped on a rattlesnake. I was heading directly to it. About 8 feet away, it rattled and at the same time, I spotted it in the light cone of my flashlight. It was very scary. At night, you can hear coyotes howling, sometimes uncomfortably close. In darkness our senses heighten and we may get startled even by something as trivial as an owl’s hoot. I usually end up talking to myself out loud to give me the illusion that I am not there alone. This also helps against mountain lions because they never attack a group of hikers. I am sure a mountain lion has seen me even though I never saw one myself.

Having pointed out the dangers of wildlife, when I shoot at night the primary feeling is not fear but amazement. Nature is incredibly beautiful at night, and being fully aware of this beauty makes me forget about the dangers. Once I start shooting, I am 100% in the moment and time loses its meaning. I often catch myself that two hours have passed that felt like 10 minutes. Picture taking can be a very therapeutic and meditative experience.

You were trained as an engineer. How do you think this training has affected your approach to photography? Did you take any number of courses in art, or art history, or photography, when you were in college?

I went to a technical college where art was not even an option. My love for fine art comes from my family, watching my father paint, sketch in the field, mix paint, and use different techniques. We had a lot of art books on our shelves at home that I could browse through. When I was at the elementary school, I loved to draw. I would draw Disney characters in my notebooks regardless of the subject to the point that would drive my teachers crazy. Everyone thought that I would be following a degree in fine arts. Then, in middle school my interests widened to astronomy, I self-taught calculus myself in 8th grade, and once I realized its power, I was hooked for life and became an engineer. Even though my artistic heart went dormant for a while, it has always been there and now came back with full force.

Who, or what, has had the most influence on your photographic work? What photographer do you most admire?

I love the work of Michael Fatali and especially his what I call landscape portraits — images in which there is a clear subject rather than your typical wide-angle landscape. He was among the first who photographed the formations in Vermilion Cliffs National Monument and came up with numerous compositions that are considered classic today. I admire the work of Marc Adamus and astrophotography of Dave Lane and Wayne Pinkston. Bill Belvin’s thewave.info is the best source for southwest explorers together with the books of Laurent Martres.

Do you do much in the way of photographing people? Architectural subjects? Other “objects”?

Not at this point. When I travel with my family, I just grab my point and shoot camera because I do not want the picture taking to interfere with family quality time. Having said this, I wished on numerous occasions I had my full gear with me but one cannot sit on two chairs at the same time.

Other than the Southwest, which you have explored in a such a fascinating way, where else would you like to shoot?

There are too many places that appeal to me and that I would love to photograph. So far, I only dibbed in the beautiful and vast Northwest part of the US. Alaska, Iceland, Patagonia, Norway, too many to even list. I would also like to explore off beaten places in Canyonlands. In fact, this is what I originally wanted to explore but then came across the less known Vermilion Cliffs and left my heart there. I am a creature of habit. I love to come back to familiar places.

Is there anything you would like to say or add to this interview that I have not asked?

I would like to stress that the real link between my work and photography is not the fact that I research digital images but the process of discovery. I get the same feeling of excitement when I discover a new algorithm as when I discover a new composition in combination with a creative use of light. Both are the results of an exploration, venturing where no one has ever been before. And both require “going in” with my heart and passion. So, I would like to tell the readers to not be afraid to pursue their passion, whatever it is, with their heart fully open. When you do it, good things will happen.

Interview by Mike Foldes

Mike Foldes is founder and managing editor of Ragazine.CC.

Jessica Fridrich is Distinguished Professor in the Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering in the T. J. Watson School of Applied Science and Engineering at Binghamton University, Binghamton, N.Y. For more information about Jessica and her work, visit http://www.ws.binghamton.edu/fridrich/ and http://www.jessicafridrich.com.