I imagine him watching people – especially the women – as he sits at his table at Café de Flore. In fact, Jeanloup Sieff writes in his memoirs: “With each woman that passes, I live out a love affair, fleeting but complete. When I see them some way off and their silhouette attracts me, our idyll begins. The closer they come, the more I love them. At ten metres it is passion; at six, painful jealousy; at four, it’s unbearable: the heart-rending separation has already begun. And by the time they pass me, I am released and relaxed and smile calmly at them. They have become my friends, and we can exchange the conspiratorial glance of those who have experienced many things together and remember them all.”

The Seventies marked the beginning of a new chapter in society and in Sieff’s life. He had returned to Paris and was living with Barbara Rix, one of the models he had worked with in the past. The world was in upheaval. The vibrant enthusiasm of the Sixties experienced its first setback: the joyous, carefree hippie mentality was replaced by feelings of crisis and rebellion that overturned all the rules. Jeanloup Sieff observed the changes from his table at Café de Flore. Then, as he was wont to do, he decided to celebrate the start of the decade with an iconoclastic gesture: taking a picture of a nude Yves Saint Laurent. It was a scandalous and contemporary act: the modernity of denuding a male body. Then he blew us away by portraying him entirely clothed, complete with bow tie (page XX).

Regarding fashion (and society), the Seventies were indissolubly tied to a synthesis of the sexes, which first occurred through the widespread use of trousers, and the affirmation of seductive femininity. Ironically, that symbol of joyous liberation called the miniskirt made way for new portrayals of the female body in public. A woman’s success was no longer measured by the shortness of a hem, which now came in a wide variety of lengths. In Paris, women discovered the androgyny of the tuxedo. In New York, they flaunted their figures in body-hugging wrap dresses. Helmut Newton and Guy Bourdin played at hyper-sexualizing bodies and creating a photography style that was blatantly sexy, which infuriated the feminists who did not catch the irony of the gesture. Newton’s message was clear: women are objects – the Alpha women of the future.

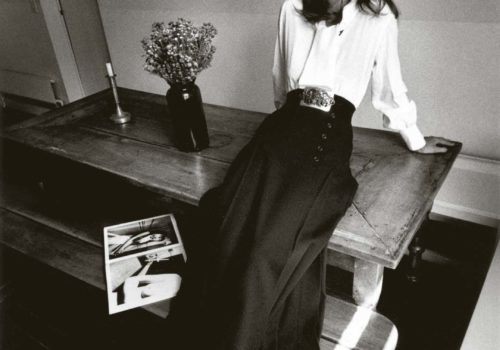

Jeanloup Sieff, however, chose a different perspective that was not a contrast or reaction but a supplement. He used a timeless classicism to create an aesthetic that was as elegant as it was difficult to date. He built his own visual world that is not immediately perceived, but arrives on tiptoe. Quietly but with a distinctive style, Sieff overturned the linear conception of time that had defined fashion up to then with another (almost) transgressive gesture. His photo of a dress from Saint Laurent’s “40” collection (page XX), whose retro allure scandalised Parisian ladies, not only marked the beginning of a trend that is now universally accepted (interpreting the language of fashion by reviewing the grammar of the past), but also launched a new timeless aesthetic that Sieff developed throughout the decade. It was as if, while the collective imagination sailed without charts, he decided to drop the anchor, uninterested in the uncertain horizon but looking at and enjoying the journey.

It might seem a form of nostalgia – Sieff used to say he was a “nostalgic” – but that would be reductive. Rather, it is interesting to think that he wanted to escape from the madness of those years and the series of styles, fads, and attitudes that in just a decade brought together the hippie movement and punk generation, environmentalism and a “no future” rage. He and his friend Jacques-Henri Lartigue presented a sequence of joyous and nostalgic images at the Les Rencontres d’Arles festival. Both cultivated a particular view of photography, which they considered a pleasurable activity, but also a search for lost time. In fact, Sieff also became an editor and published the books of three photographer friends – Duane Michals, Martine Franck, and Robert Doisneau – to whom he gave carte blanche.

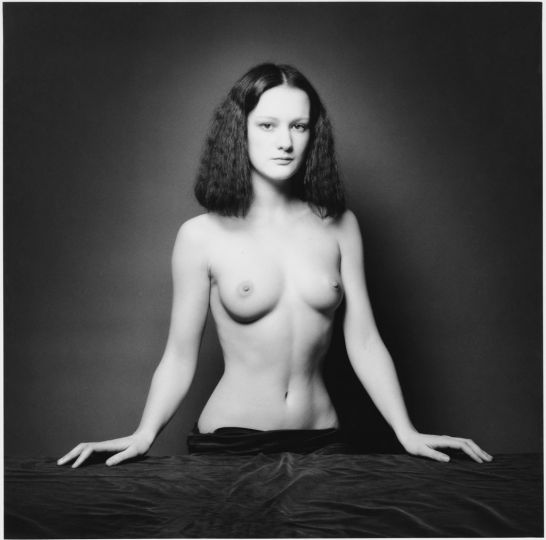

Even his famous nudes from the time reflect a delicacy and lightness more in tune with the imaginary années folles, the Twenties, than with the blatant freedom of the Seventies. His style is pure and instantly recognizable: incisive black and white, precise contrasts, and perfect lighting. “Cartier-Bresson spoke of the decisive moment. I think that decisive lighting is essential in a photograph,” he said. Obviously, the harmonious composition of a certain space, or simply the use of space, was just as essential, as was the position of the bodies within it in a sort of immobile, sinuous, elegant dance. Significantly, Sieff’s first love was ballet, and he frequently took pictures of the ballerinas of the Paris Opera. He was fascinated by those bodies and by the grace and fluidity of their movements. He remembered those images, and we find them in his photographs: invisible choreographies crystallised in the purity of a gesture.

In the collective imagination, the Seventies were considered a period of accumulation: of styles, ideas, images and colours. Jeanloup Sieff worked by elimination. The set was reduced to a bare minimum, lighting was calibrated to an almost unreal perfection, and the body emerged in all of its purest simplicity. Sieff made an aesthetic choice that was an important statement: he opted for the freedom of portraying beauty that transcended the aesthetic rules of those years. He continued to amaze us through images that were only apparently simple. In that decade of confusion, Jeanloup Sieff created a world of unity and harmony. He did not portray fashion the way it was or the way it should have been, but seemed to arrange elements in a new socio-sensual narrative.

In fact, in the Seventies he focused on torsos seen from behind and, in particular, on the derrière (page XX). In one of his last interviews with the newspaper Libération, Sieff said: “The derrière is the part of the body I prefer. That’s because I’m a born nostalgic, and the derrière preserves memories: it faces the past and doesn’t care about an uncertain future.” While he sat at his table at Café de Flore, I can easily imagine that Sieff’s favourite moment was that fraction of a second when the woman he was observing was about to disappear around the corner. After she was out of sight, Sieff could savour the pleasure of his nostalgia, not for that woman, but for a particular, indefinable sentiment that made her unique and eternal in his eyes.

Franca Sozzani