Magnum photographer Bieke Depoorter gained attention for work arising from a three-month travel trip across Russia, using the Trans-Siberian Railway, and it helped gain her the Magnum Expression Award in 2009; her first book, Ou Menya, appeared two years later. A similar kind of project brought her to the United States and resulted in I am about to call it a day, published in 2014.

Depoorter has been visiting Egypt since the beginning of the country’s revolution in 2011, evolving a distinctive form of documentary photography as a consequence in the process. |In her travels, she avoided the uprising centered around Tahrir Square and the political turmoil that followed; instead, she sought out family spaces where the public events could be excluded.

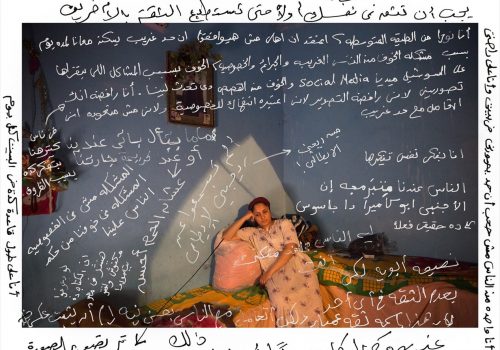

The 44 photographs, taken inside the homes of ordinary Egyptian families, record everyday domestic moments: a shy boy hides behind a curtain; a mother puts her children to bed; a woman applies makeup in her bedroom; a teenager poses; a woman plays with her grandchildren.

The colors are vibrant, lurid at times, jumping out from painted walls, decorative upholstery, richly hued carpets, fabrics enlivened by glorious mixes of dyes. Different moods are evoked – melancholy as much as happiness – and it seems clear that the individuals have allowed themselves to be pictured, trusting the photographer.

In 2017, Deeporter returned to the country with a first draft of As it may be and invited others to write comments directly onto the photographs. The final book in its published form includes the comments: the result is a fascinating palimpsest and a conversation, conjoining the visual and the verbal, between photographs of domestic moments and written responses to these scenes by Egyptians (translations from the Arabic are provided in a 60-page booklet at the back of the book). Turning the pages of this very handsomely produced book from Aperture reveals not just the individual images but the strange experience of eavesdropping on some conflicted and critically-minded tête-à-têtes.

The scribbled remarks are curious: usually highly specific, invariably interesting, often questioning and probing. Out of the window of a poor household’s kitchen can be seen the outline of a pyramid and this provokes doubt: ‘I can’t believe that there are houses like this near the Pyramids. Because the Pyramids are in an upscale area’, writes someone over a frame of the window; ‘A picture of the house of someone poor, to make the rich think about how they need the basic requirements for a good life’, scribbles another who provides two telephone numbers for anyone wishing to help the owner of the house.

A photograph of a woman with children asleep alongside her under a shared blanket makes someone exclaim: ‘You cannot photograph a woman while she is sleeping, because a man might see her’; another comment concurs: ‘Eating and sleeping are private things. You should not be exposing them, they should be hidden’; but someone else disagrees: ‘I’m not really bothered by the idea (the picture).’

Men are noticeable absent from the pictures but one of the exceptions shows a husband in his abaya sitting in a living room, his wife resting on the floor, while an electric fan circulates the air and a child stands by a door in relative darkness. The comments vary from praise (‘This is the deepest picture’) to criticism (the picture is ‘wrong’ because it shows a woman sleeping) to the sensing of marital discord (‘when there are conflicts between the mother and the father, it affects the children’).

In an accompanying essay in the book, Ruth Vandewalle provides invaluable background information on how Depoorter went about her work, gaining trust, spending nights in people’s homes, and how she went about soliciting comments when she returned with a first draft of her book.

Depoorter’s democratic spirit, inviting uncensored annotation and incorporating it into her work, brings to mind an early project by Susan Meiselas. While enrolled on a course at university in 1970, Meiselas photographed fellow lodgers in the house where she was renting a room. She then showed the results to them, asking for their reactions and pinning their written replies alongside the photographs. Depoorter, with the same impulse to go beyond the frame, has gone one step further and the result speaks of a conservative society in the throes of change and uncertainty, though in a way that transcends the journalistic images of Egypt that became so familiar in those tumultuous years after 2011.

Sean Sheehan

Sean Sheehan is an author specialized in photography living in Sheep’s Head, Ireland. He is the author of Jack’s World, with photographs by Danny Gralton and Ciaran Watson.

Bieke Depoorter, As it may be

Published by Aperture

$60