“Did you say fashion photography?” Irving Penn, Richard Avedon, Helmut Newton, Guy Bourdin… These names, today famous, belong to photographers that have crafted a particular language to the image of fashion. What is it that makes a photograph beautiful, different, unique? Why does a picture stay engraved in our memories?

You ask me what is a beautiful fashion photograph. A beautiful fashion photograph is a picture that does not go out of fashion and that will eventually become the guardian image of the time that it was taken. These kind of pictures are hard to find, very rare. The most famous pure fashion photograph is Dovima and the elephants, by Richard Avedon, taken at the Cirque d’hiver in 1955 (according to the books, but I think it was 1956). The other photographer – through whose pictures I discovered fashion with a capital “F” (as we speak of art with a capital “A”) is Irving Penn. When I was 12 years old, my mother returned from a trip to New York (a rare expedition in the late 1940’s) with an issue of Vogue US for me, featuring the mythical series of photographs taken by him portraying the Parisian haute couture with his wife Lisa Fonssagrives, who by then was over 40 years old. Youth was not the main worry in those years. Elegance was his major worry, and Mr. Penn knew how to surpass that bourgeois notion in a superior way.

A few years ago, when I had the immense joy, honor and privilege to be photographed by Irving Penn (just for him, on his request), we spoke about this miraculous fashion series. Each image of this story is forever engraved in my memory. I knew Mr. Penn (everyone called him this, even Anna Wintour who often worked with him, and his stylist Phyllis Posnick, the only one he allowed in his studio, the loyal Phyllis), Anna had asked me to organize dinners for him when he came to Paris in the 1990s. He photographed me in New York, in the 1980’s, a portrait very different from those taken of me by my friend Helmut Newton, who himself did not like photographing men. I must have been an exception, as I have more then thirty pictures of me taken by him (including many unpublished). In the giant book of his photos published by Taschen, there are already four of them. But I am to speak of photographs of fashion and not of myself.

Geneologie of a genre

Another photograph perfectly illustrates the question: “What is a beautiful fashion photo?” It is the celebrated image by Newton of Vibeke in a Smoking by Yves Saint Laurent, taken at night on the rue Aubriot for French Vogue in 1975. Vibeke was featured in the entire issue dedicated to haute couture during that summer since Vogue was having some disagreements with the modeling agencies who were at the time boycotting Conde Nast France. From these unforeseeable circumstances was born one of the most celebrated images in the history of its “genre”. I do not say of this art, as the biggest names (Penn, Avedon, Newton and Guy Bourdin) did not use this word in speaking of their work. Helmut often said that he could never make a photo if he had to think of everything people said and wrote in regards to his photos, without mentioning all of the supposed intentions while he was doing his work.

But fashion photography existed before the “Glorious Three” (Penn, Avedon and Newton). Guy Bourdin did not have a direct rapport with this small group. They were probably not very close either, but there was a famous image (by Roxanne Lowit) that reunited the three of them. The relation or the interface between Helmut Newton and Guy Bourdin was the very missed and very courageous Francine Crescent, editor-in-chief of French Vogue in the 1970s and 1980s. She put her job at risk every month. In New York at the time, Condé Nast did not like the photographs by the two genius protégés of the dear Francine. Too daring, too erotic, almost too vulgar for them. It’s difficult to imagine this today, but the great fashion magazines were at the core very prude, if not to say hypocritical, even during these reputable years of liberty and libertarians.

I was lucky enough to know Helmut Newton and Guy Bourdin quite well. I was designing the shoe collections for Charles Jourdan when Francine and I suggested to Roland Jourdan to make his ad campaign with Guy. The result has become a part of the history of fashion photography and advertising. In reality, advertising and fashion are well mixed in our current time. Very often, the editorials of influential magazines are made by the very same photographers who shoot the ad campaigns of the major brands advertising in these magazines. The magazine editors thus ensure, in one way or another by their authority, a better image for the brands and at the same time help the photographers avoid pressure from the clients that can become sterilizing. The management of the major magazines no longer sees the problem from this angle. In the past, the editors-in-chief were themselves the stylists (a term that was not used in those days).

The dangers of retouching

There is one photograph that does not look like it has been staged, where the formidable Carmel Snow of Harper’s Bazaar arranges a dress on a model for the debonair and very talented photographer Louise Dahl-Wolfe. The trend of finding editors-in-chief present at photo shoots is more and more common these days. Carine Roitfeld was right when she said that she could not deny the magazine of its best stylist. The list of talented and influential stylists is very short. I’m not going to name them here, for fear of forgetting one that merits being mentioned. We do not often know if the final image by a known photographer is entirely his work or if it is the result of a close collaboration between him and the stylist.

Fashion photographs of today have another problem, and fashion photography runs a real risk: retouching. Many “major” photographers use the same retouching company in New York. For an exorbitant price, an embalmer’s work will be delivered, where everything looks the same, erasing the impact of the photographer. There is something terrifyingly artificial in this method. Very few photographers still do real photography when they portray fashion. Bruce Weber and Peter Lindbergh first come to mind. Nick Knight superbly knows how to apply the new digital processes with modern style and poetry, and Mert Alas and Marais Piggott are the best at retouching. They don’t send their work “outside” and perform the retouches admirably without looking as though they are pictures from “Borniol” (the funeral home company, Editor’s note). I have nothing against the superficial, Avedon used to say that one should work on the surface in order to find out what is beneath.

On the opposite end of this genre of photography, there is entire other world of photographers that seek to “witness and act as critics of the system through an apology of banality.” They believe they deliver a very committed work (and with a very costly invoice). These speeches should be left to more qualified hands and endowed with a deeper sincerity. The glossy paper of luxury magazines is a slippery ground for this kind of work. Some say that they begin with good intentions, but all they deliver in the end is nothing but pretension. An ephemeral movement in fashion photography that has not yet provided unforgettable iconic images up to now.

It is difficult for me to be objective when discussing fashion photography of today. The fashion photographer by excellence remains Steven Meisel. He loves fashion and he is not ashamed of it. He is not obsessed by the notion of art and museums. He has no contempt for fashion. Helmut Newton used to say that fashion magazines were a brilliant invention because they would supply the most beautiful girls for free and everything that goes with it. Helmut, who did not like to spend money, never had a real studio. Avedon’s studio, for example, was very “New York”, but did not resemble all of the high tech installations at Pier 59. The most modest studio I have ever been to was Penn’s. We could never have imagined that so many works of art could be produced in such a tight place. It was a small apartment on 5th Avenue, made available to him in perpetuity by Condé Nast, who certainly did not hurt its financials for this decision, compared to what he would deliver in exchange for Vogue. The entrance was used for portraits. There were two chairs and a picnic table near the window (Mr. Penn would love to chat with his “subjects” before the shoots near a stained mattress, that appeared in many famous portraits). There was a small room for the still-life photos (and what still-life photos!) and another room for fashion. The kitchen served as an office, with the lamps and cameras from the 1950s. One would have the impression that nothing new had been purchased since then. Why, then? Because he could create works of art with that rudimentary equipment.

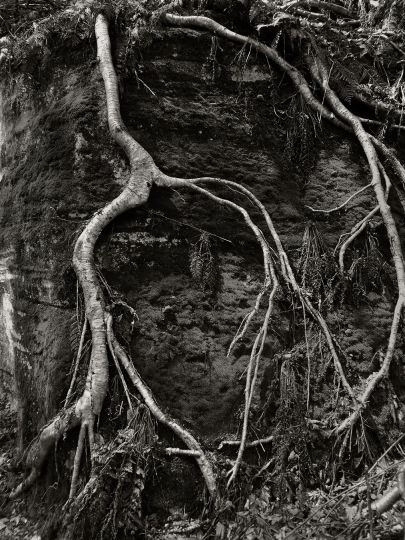

But fashion photography did not begin with the admirable Mr. Penn. The first fashion-fashion photography, in my opinion, is by Steichen (one of my gods), showing three girls wearing turbans in the stairs in Poiret, around 1912. In the past, it was most of all documentation, and elegant fashion was drawn. By Georges Lepape first, and then by Benito, Eric, Vertes, Bérard. Then, Gruau appeared, and he knew how to immortalize the women in the 1950s like no one else. Antonio’s work has left an image as strong as fashion photography from the 1960s and 1970s.

Art cannot be explained

People ask me if fashion photography is an art. It is an applied art, the same goes for illustrators, but very few have gone on to become great “artists” in the public eye.

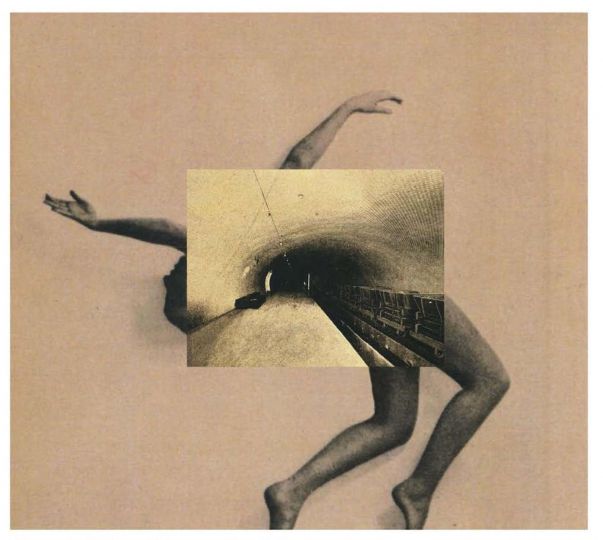

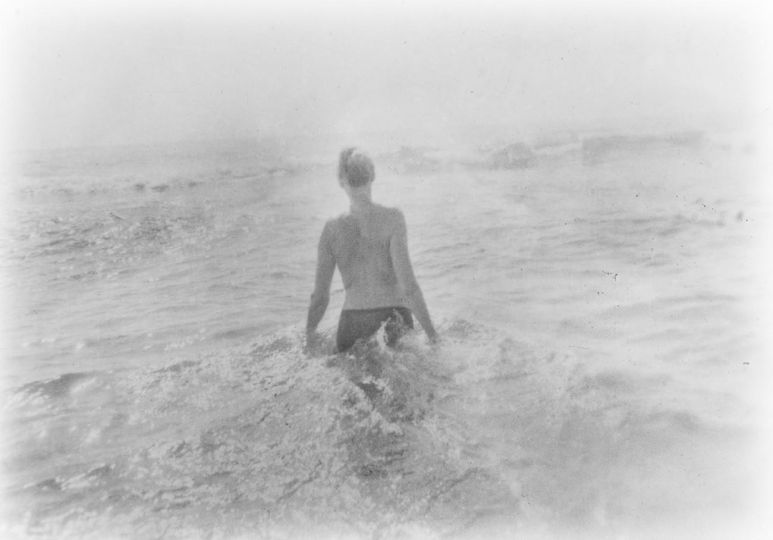

Man Ray was not a fashion photographer in the same way as Newton, Penn or Avedon. Martin Munkâcsi, Avedon’s master, was the first to have photographed (already before the war of 1939-1945) models in movement. It was a reporter from Berliner lllustrirte Zeitung, who had left Germany as so many genius’ did, in 1933. This exile had almost completely deserted Germany intellectually.

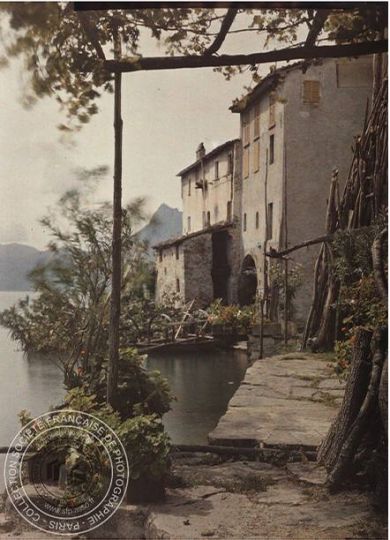

I also have a weakness for the Baron de Meyer, almost forgotten today. He was one of the first great fashion photographers, before Steichen, for Vogue US. His lighting was magical and the ensemble of his work was highly poetic. Yet it was precisly this that made his work go out of fashion. Subsequently, Hoyningen-Huene and Horst took his place at Vogue.

We often forget that Avedon spent a large part of his professional career at Harper’s Bazaar. Dovima and her elephants, the photo previously mentioned, was in fact made for Harper’s Bazaar.

I began my article with Dovima and the elephants, and I will end with it. The circle is closed. I could write pages upon pages on fashion photography, and I have the feeling that I unjustly forgot many people whose work I admire. For me, it is about artists, but I am not an arbitrator to say what is art and what is not art.

Massenet said there was not great or small music, but only good or bad music. For fashion photography, it is quite similar. I am against all intellectualized discourse of this domain, and in referencing Voltaire: “What needs to be explained does not deserve an explanation”. A good fashion photograph equally speaks alone.

Karl Lagerfeld. Published in Le Monde, “M” magazine, the 3th of February 2011.