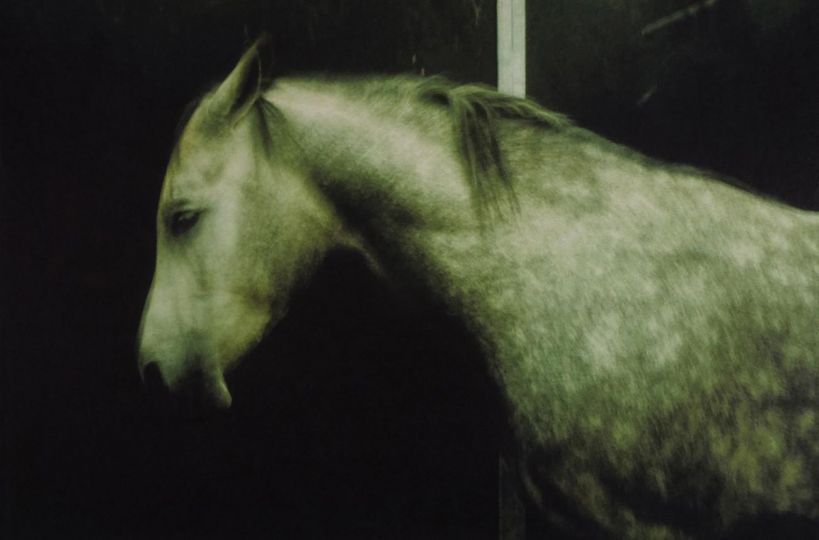

Deborah Bell Photographs presents E.J. Bellocq: Storyville Portraits. Thirty-six printing-out-paper prints, made later by Lee Friedlander from Bellocq’s original glass plate negatives, will be on view.

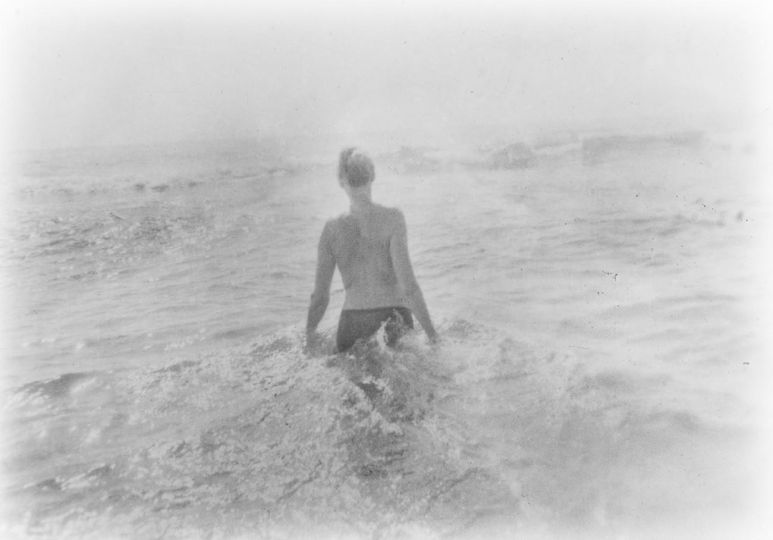

E.J. Bellocq (American, 1873-1949) remains an ambiguous figure in history. Following his death in 1949, eighty-nine glass plate negatives of portraits of female prostitutes from New Orleans’ Storyville district were found in his desk. All of the images were taken circa 1912 by Bellocq, who was a commercial photographer practicing in New Orleans. Photographer Lee Friedlander acquired the plates in 1966 and made contact prints of the 8 x 10-inch negatives on the same gold-toned printing out paper that Bellocq used in his rare prints. Friedlander is credited with salvaging and promoting these pictures, the only aspect of Bellocq’s work known to have survived. The mystery surrounding the photographs and the personality of E.J. Bellocq is furthered by the fact that many of the plates were cracked, scratched, or damaged at the time that Friedlander acquired them. In 1970, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, exhibited a survey of the Bellocq prints made by Friedlander, and published E.J. Bellocq: Storyville Portraits, edited by John Szarkowski and Lee Friedlander. A second monograph, E. J. Bellocq: Photographs from Storyville, The Red Light District of New Orleans, edited by Friedlander and Mark Holborn, was released in 1996.

In his preface to E.J. Bellocq: Storyville Portraits (1970), Lee Friedlander relates his experience of discovering Bellocq’s glass plates in 1958, and how he came to make the prints after acquiring the plates in 1966:

I met Larry [Borenstein] in 1958 while listening to Kid Thomas’ band in Larry’s art gallery on St. Peter’s Street near Bourbon, where many great New Orleans jazz bands would come to play – a story in itself. Among his treasures at that time were the Bellocq plates, and late that night after the band had gone, Larry showed them to me.

Late that year, or maybe the next, when I was in New Orleans again to listen to jazz and to photograph for myself, I asked Larry if I could see the Bellocqs again. At that time, too, he gave me a print. … In 1966 I decided I would ask Larry if he would let me either purchase the plates from him or borrow them to make good prints. He agreed to sell them and I packed them and came home to print.

I soon found I could not use my conventional method of printing, as the plates did not respond well to bromide paper. The tonal range was too limited even on the softest grade. Some research led me to a printing technique popular around the turn of the century called P.O.P. (Printing Out Paper) which has an inherent self-masking quality. In this method the plates were exposed to the P.O.P. by indirect daylight for anywhere from three hours to seven days, depending on the plate’s density and the quality of the daylight. Then the paper was given a toning bath of the gold chloride type. Fixing and washing were done in the usual manner but with great care, in that P.O.P. emulsion is especially fragile.

The Storyville portraits have continued to fascinate and spark discussion about Bellocq’s relationship to his subjects. In her eloquent essay, Bellocq Époque: The “Storyville Portraits”, published in the May 1997 issue of ARTFORUM, the photographer Nan Goldin writes:

When one thinks of the massive amount of negatives and glass plates one comes across in flea markets and thrift shops, Friedlander’s power of discrimination becomes even more admirable, rivaling Berenice Abbott’s rescue of Eugène Atget’s work from oblivion.

At the turn of the century…the experience of being photographed was far different. At that time, it would have been a special occasion, a form of attention that required time and collaboration. In spite of the large, unwieldy 8 x 10 camera, Bellocq’s pictures appear natural, and the women seem open and trusting. There’s a nonthreatening presence with an unprecedented degree of empathy permeating his work, rather than the usual sense of someone in a power position objectifying his or her subject. Bellocq’s photos do not show prostitution as a reductive identity.

Bellocq never betrays his respectful and nonjudgemental position in his protrayal of the women. That they are prostitutes does not preclude the fact that some of them are shown as ordinary young women. They seem to have posed themselves, choosing from an enormous variety of identities. Some pose like Pre-Raphaelite heroines, others like college girls with school banners, while some recline in interiors as opulent as Turkish opium dens. There are girls in gymnasts’ outfits, in pantaloons and homely nightcaps, and others hold their little pet dogs. … Many are ladies dressed in all their finery who look like they are on their way to a garden party.

Whatever Bellocq’s intentions were, whatever the nature of his relationship to these women, his portraits transcend the portrayal of the prostitute as an object. … In the end, “Storyville Portraits” remains a unique collection of love poems.

This exhibition is held in association with Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco.

E. J. Bellocq : Storyville Portraits

from February 15 – March 28, 2020

Deborah Bell Photographs

16 East 71st Street, Suite 1D

New York NY 10021

www.deborahbellphotographs.com