The Centre Pompidou presents a dialogue between Lynne Cohen and Marina Gadonneix, two photographers who share an interest in the interior spaces of our modern societies, from places of scientific study to places of entertainment and consumption. Although the spaces documented by both artists are marked by the absence of human figures, their traces remain visible, inviting us to better understand and protect the social and natural environment. We publish here extracts from the exhibition catalogue, co-published with Atelier EXB.

Florian Ebner 8 “Message From the Interior” The Work of Lynne Cohen Through Its Variou Readings

There are many stories in the history of art about those epiphanies when an artist comes across the work of a colleague, moments of instant attraction that have subsequently changed their own thinking and artistic production. Take, for instance, the young French photographer who, in about 2000, discovered Lynne Cohen’s book Occupied territory, at the library of the École nationale supérieure de la photographie in Arles. From that moment on, the Canadian artist’s work would occupy a major place in the imaginary museum of Marina Gadonneix, who years later in late 2013 finally decided to contact her older colleague thirty-three years her senior. It was Lynne Cohen’s death in April 2014 that put an end to a budding correspondence. The double exhibition Lynne Cohen/Marina Gadonneix: Laboratoires/ Observatoires continues this dialogue through their works.

Dual Contextualization

This catalog devoted to Lynne Cohen, one of the twin books published on this occasion, adopts the trope of exchange to offer a dual contextualization of the oeuvre by the Canadian artist, born in 1944 in Racine (Wisconsin). First, it offers a better understanding of the first twenty-five years of her creative output. The artist, who turned to photography around 1970, developed an immediately recognizable approach, and narrowed her focus to the representation of interiors, with conceptual and formal rigor, a subtle sense of humor, a fresh “coolness” that would serve as a model and source of inspiration for other generations of artists. This publication’s second focus is to understand why Cohen became an artist’s artist and to better gauge the extensive reception and recognition of her work in Europe, especially in France. In this sense, the exhibition is not a retrospective, but more of a specific and detailed study that examines the latent impact and current relevance of an oeuvre that turns out to be in dialogue with the generation that followed her. The first context will be reconstructed through a number of texts and a visual atlas.

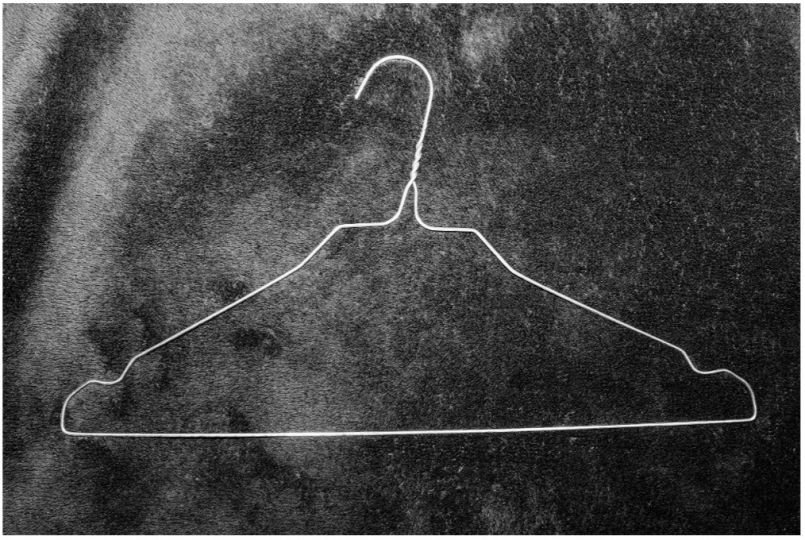

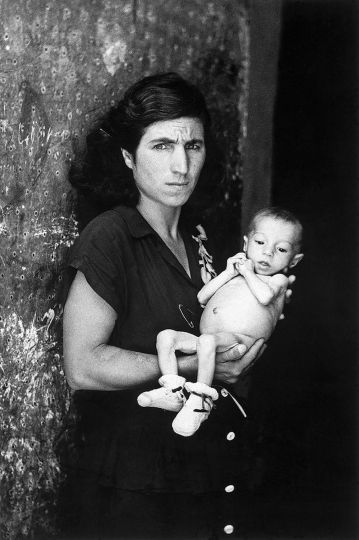

Essays by Matthias Pfaller and Jean-Pierre Criqui reveal how Lynne Cohen’s work relates to American “social landscape” photography as well as minimalism, pop art, and conceptual art in the 1960s and ’70s. The text “Lynne Cohen: A View from Sideways on” by Andrew Lugg, Lynne Cohen’s husband and intellectual accomplice for fifty years, and an extensive biography both focus on Lynne Cohen’s trajectory. The illustrated section at the center of this book ventures to present Cohen’s work in another way than the artist used to show it. It proposes a kind of atlas grouping together the various categories of places and sites—the artist herself speaks of “themes”1—on which she worked on and off and in parallel throughout the first twenty-five years of her photographic output. Far from striving to be a catalog raisonné or turning these themes into rigid typologies, this atlas shows the development of a body of work that began in the early 1970s with an interest in private and semi-private interiors (living rooms, men’s clubs, and banquet halls), all clearly bearing the imprint of different social strata, and then over the course of the 1980s turned toward the increasingly functional and sterile places (laboratories, observation rooms, shooting ranges) of our governing and controlling societies. These constellations reveal the systematic mindset of the artist who would look for the same types of places in the telephone directory, such as the banquet rooms of different ethnic communities,— indication of her social interest (see p. 46–47). They also provide a glimpse of some common features that transcend categories, of fantasies that haunted the artist’s imagination, as well as her attentiveness to particular patterns, certain motifs embedded in the everyday existence of these “readymade installations,” recalling artists’ styles or forms of art. The same fashion for wall decorations with motifs inspired by chronophotography can thus be seen in an office (see p. 36), a showroom (see p. 37), and a laboratory (see p. 75), for instance. The major significance of Walker Evans’s work becomes palpable in the first plates of the atlas, a lead-in to the question of different readings and misreadings, appropriappropriations and hybrid forms that are at play, both in the constitution of Lynne Cohen’s work and the interpretations it engenders. This is how the genealogies and family trees in the history of photography are formed.

An interview with Marina Gadonneix by Florian Ebner and Matthias Pfaller: Recording in Progress

Florian Ebner:

The exhibition Laboratoires / Observatoires at the Centre Pompidou presents your work and that of Canadian photographer Lynne Cohen in dialogue. Apart from similar themes and approaches, there is also a more personal connection. In a short text that you dedicated to Lynne Cohen’s work, you said that you carry her book Occupied Territory around with you and have done so for a long time. What are the dynamics in her work that have also influenced yours?

Marina Gadonneix:

While I was studying at the École nationale supérieure de la photographie in Arles, my teachers introduced me to German photography, particularly the Düsseldorf School. When I discovered Occupied Territory in the early 2000s, I found a kind of freedom in Lynne Cohen’s work. An energy, a curiosity, which had taken her to a wide variety of places. While, at the same time, she was reporting on a changing world, a world under construction, an evolving world that people were struggling to understand but were failing to look at head-on—or weren’t taking the time to do so. And her take on it, too, was stripped of all human presence in order to shed light on its paradoxes. Occupied Territory was different from anything I had seen; it was not about series, subjects, or typologies. Lynne Cohen’s approach was witty and at the same time sinister. It was funny and disturbing; not anecdotal, but still imbued with empathy. It is precisely that energy, when I’m filled with doubt, like a writer’s fear of the blank page, that carries me on. Maybe because I share the same curiosity in my research.

Matthias Pfaller:

Lynne Cohen was inspired by Walker Evans, and that’s what motivated her to get out of the studio and into the world. Your work, too, is characterised by a quest for different locations, to collaborate with researchers and explore different environments.

Marina Gadonneix:

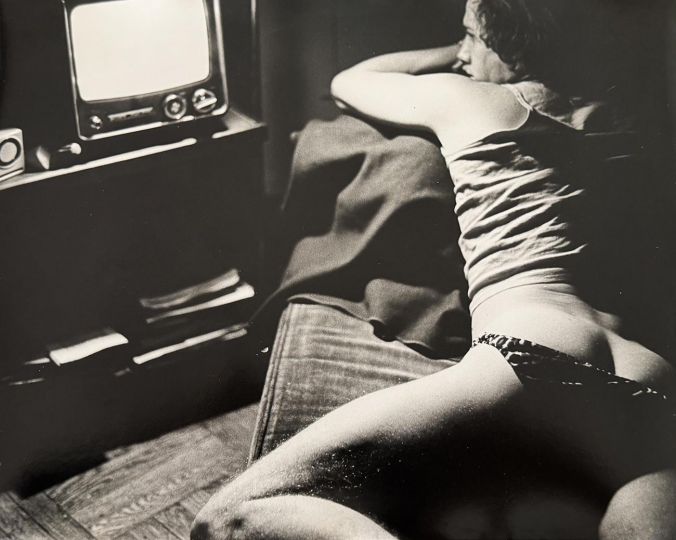

I share Lynne Cohen’s interest in society and how it looks after having been constructed and cobbled together by people, but also the importance she attaches to creating an image of society. Basically, I share the same interest in unseen places, places that we don’t notice. I began by questioning the idea of creating an image, perhaps taking inspiration from her, exploring the whole question of artifice and factitiousness. But like her, I don’t aim to be judgemental. In the early photos, I was just fascinated by those cardboard desks and aquariums. “Remote Control” is different. It’s about mise-en-scène, in this case television—what we are all exposed to in our living rooms. But rather than specific televised content, it was the test card—the image of a colour chart that people can use to adjust their screens—that I was attracted to. So I dropped the issue of artificiality and began to consider those test cards as screens that somehow come across as images within the image, a kind of landscape in our living room. As for the “Landscapes” series, it’s not about artifice or mise-en-scène. What interested me in that project was the question of the disappearance of the decor. There is only one monochrome colour, green or blue, which physically exists in places that are hidden from us or that we have to search out in order to gain access to them. I also go along with Lynne Cohen on the question of secret things. That’s why in my text “Deux images d’elle” [Two images by her], I wonder about what fascinates her—whether it is the same fascination that drives me to go rummaging around, looking at what people construct, trying to understand where the world is going (sociologically and politically), but without aspiring to be a documentary photographer either, although reality is always a starting point. The trajectory of my work has been a series of thoughts on the question of mise-enscène clearly influenced by what I had learned from Cohen at first, then moving towards a more virtual image with “Remote Control”, then the disappearance of the decor with “Landscapes”, and eventually returning to the question of the scientific laboratory via the representation of catastrophe. In short, it’s still a matter of mise-en-scène without human presence in order to show places more effectively, how they have been built and devised, and what it reveals about the times we live in and about current generations, However, having been trained in photography and cinema, I didn’t immediately have many thoughts about painting and sculpture. It was only with the series “Après l’image” [After the Image] that I suddenly started to think about it, and particularly about minimal and conceptual art. So I started to investigate and get further into approaches that I hadn’tencountered much during my studies. Lynne Cohen, on the other hand, comes from a rather different approach, in the sense that she came to photography through minimal and conceptual art. So, in “Après l’image”, I became interested in the work of James Turrell and Imi Knoebel, and the work of other artists of my generation, such as Béatrice Balcou, whose work I knew of course, but which I hadn’t studied in great detail yet.

Our warmest thanks to the Musée national d’art moderne and its Cabinet de la Photographie, to its curators Florian Ebner and Matthias Pfaller and to the Atelier EXB for making this publication possible.

Lynne Cohen / Marina Gadonneix: Observatory / Laboratories

From 12 April to 28 August

Curators: Florian Ebner, Curator and Head of Photography Department, Mnam-Cci

and Matthias Pfaller, guest curator, Alfried Krupp von Bohlen und Halbach Foundation

Musée national d’art moderne-Centre de création industrielle,

Galerie du Musée and Galerie d’art graphique, Centre Pompidou

75191 Paris cedex 04

+ 33 (0)1 44 78 12 33