Bamako is hot. Very hot. 70° mornings seem almost cool compared to the scorching 95° days. All the more so because the sandstorms, light though they may be, pollute the dust to make it all the more oppressive. Just two days ago, as the fog drowned the early morning, fishermen’s pirogues floated on the river like faint commas. The heat was still crushing. The fog, though it dissipated the day after like a mirage or a fever dream, interrupted air traffic, postponing Peter Hugo’s arrival, whose journey from South Africa had been arduous. He did finally manage to arrive but his luggage did not— it included, among other things, photographic equipment and prints for the workshop and masterclass he had come to lead, on the occasion of the 9th Rencontres de Bamako, at the Conservatoire des Arts et des Métiers Multimédia. But it would all work out.

It’s hot in Bamako, but the thousands of helmetless motorists carelessly weave their little Japanese motorcycles between cars. The market sidewalks teem with pedestrians, joggers, and an abnormally high concentration of goats— magnificent goats. Some seem almost aware of the fate that awaits them on the November 7 holidays of Eid al-Adha. The goats would replace sheep for less fortunate families. Goats, although surprising in their number, are unremarkable in this town where animals are unavoidable. Little trotting grey donkeys pull their carts proudly through clouds of exhaust. The Malian capital is distinguished by roundabout after roundabout, imposing bronze hippopotamus sculptures, the insides of their yawning mouths painted red. And everywhere, in the little parks, in the courtyards of public buildings, painted concrete buffalo and gazelles seem as though they had always been there, and always will be. In front of the strange architecture of Memorial Modibo Keita, not far from the Monument de la Paix where an immense dove protects a tiny globe, are three concrete crocodiles, lost, lying at the bottom of a waterless fountain.

They welcome visitors to one of the five exhibition halls where the Biennale will take place. After five minutes at the Memorial, one already has a decent idea of the orientations of this year’s exhibition, the subtitle for which, “For a sustainable world,” seems more opportunistic than photographic, but nonetheless confronts the reality of pollution, the unchecked exploitation of natural resources, the disorientation of man in his relationship with nature, the chaotic development of cities that produces outcasts of all ages. In the modern buildings (although not ideal in terms of installation and presentation) the anguish builds as the reinforced concrete walls reject all but the biggest nails and the heat renders even the best double-sided masking tape useless. But it would all work out. And we could appreciate, in the large-format photographs sent from Paris (DUPON and PICTO associates, CIRCAD for the assembling), Georges Osodi ’s stance in reaction to the ecological and humanitarian disaster caused by the pollution of the Niger delta by the petroleum industry. There is also the violence, photographed with elegance and sensitivity, of “The Hell of Copper” (L’enfer du cuivre) in Ghana, when Nyaba Léon Ouedraogo descends into the piles electronic waste, or the vibrant colors reflected in the typhoid and malaria-saturated sewage of Kinshasa, photographed by Kiripi Katembo, surprisingly calm in this quiet denunciation. In the same room, in the form of still images and projections, we also find the indispensable echo of the “Arab Spring,” especially in Tunisia and Egypt. Nermine Hammam’s ironic photomontages from Cairo, the participative collages by Artocratie, Inside Out by JR in Tunisia, like Faten Gaddes and Khaled Hafez ’s video montages show how unnecessary it is to limit oneself to images from the headlines. A beautiful opening.

En route from one exhibition to another, trying to find shortcuts around the traffic jams filling even the immense Martyrs Bridge that straddles the river, surrounded by taxis, scooters and pedestrians, one occasionally passes a fresco that makes the hundreds of meters of red-and-white Coca-Cola advertisements almost ridiculous: in striking yellow and red, a gigantic advertisement proclaims the benefits of Maggi soups: “Every woman is a star.” It takes twenty minutes to extract onself from the snarl of vehicles clogging the roundabout next to the Musée du District, but it’s worth the trouble. On the first floor, a beautiful installation by David Goldblatt brings together his documentation of Johannesburg, accompanied by long and detailed texts, and his portraits of ex-convicts photographed at the scenes of their crimes. Through a limited palette of colors, flawless in their precision, the artist offers a perspective that reinforces this feeling that the history of apartheid is far from over, and that this politically committed master documentarian, now eighty years old, continues his work with a steadfastness that commands respect. In a dark room on the ground floor, the colors of Abdoulaye Barry’s “Pêcheurs de nuit” (Night Fishermen) gently emerge from the shadows. But one has to wait to see them more clearly, because the light switch is hidden behind one of the picture frames and is not accessible on opening day. But it would all work out.

There are exhibitions at the Institut Nationale des Arts (such as that of Nii Obodai from Ghana, whose black-and-white entries are fine but uneven) and at the Institut Francais (Philippe Bordas’ remarkable “Hunters”) that will only be hung at the last minute. Because all of the next week at La Lettre will be dedicated to the Rencontres de Bamako, and we will cover all of the artists then, let us hurry before traffic gets too bad to the strategic heart of the festival, the Musée National du Mali.

This is where Samuel Sidibé, director of the Museum and managing director of the festival, works tirelessly. He has to supervise everything, solving visa problems with French authorities while cheering on a street sweeper with his ear glued to his cell phone. His office is part beehive and part squat. There, one can find Laura Serani and Michket Krifa, the artistic directors, and Catherine Philippot coming to meet a journalist whom an early-arriving artist came to greet. Samuel responds to everyone, courteous as ever, affable, efficient and calm.

The Museum, located in a park that opened a little over a year ago, displays clay models of architectural designs in perfect scale. In addition to studios and workshops, the museum will host an exhibition of large-format photographs printed on canvas tarps and hung on wooden panels. Despite the heat, despite the sand, they build, they move. Everything has to be ready to receive the numerous artists, guests and journalists at a greatly important exhibition with a budget that is nonetheless around a million euros. Sometimes the heat makes things difficult. But they carry on, and it all works out.

It’s cooler in the air-conditioned rooms though not quite as cool as some restaurants, which feel more like igloos. Everything is coming together. The notable historical exhibit with Soungalo Malé (a revelation), and the work of Abderramane Sakaly and Malik Sidibé assure us that the collection of visual memory continues, and the reexamination of history continues. For the first time, Sindika Dokolo, an African businessman and collector, shares a portion of his photo and video treasures, selected by Simon Njami. It’s an incontestable sign of maturity.

But the heart of the festival is undoubtedly the enormous and diverse Pan-African exhibition on display in a space designed by Franck Houndégla. 45 photographers and 10 videographers from 27 countries: that’s what I call ambition. This is the opportunity to give space to diverse aesthetic styles and promote their creators. This is politically engaged photography, a product of necessity, and even if it concerns itself with its form it is far from decorative. The portraits, though internalized, question identity. The numerous landscapes offer perspectives on the degradation of space and of construction and its stakes; they are not displays of mere beauty. The documentary approach, dominant here, is torn between a blunt observation and a restrained cry: accusatory but ineffective. We leave with the feeling of an “Africa,” however diverse she may be—and she is terribly diverse. We also leave with the feeling of the power of photography and a dynamic operating on pure necessity. That’s not insignificant.

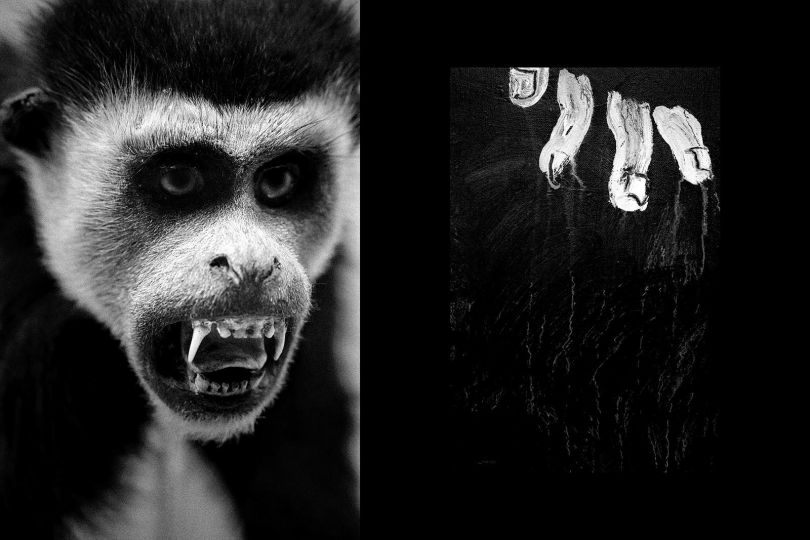

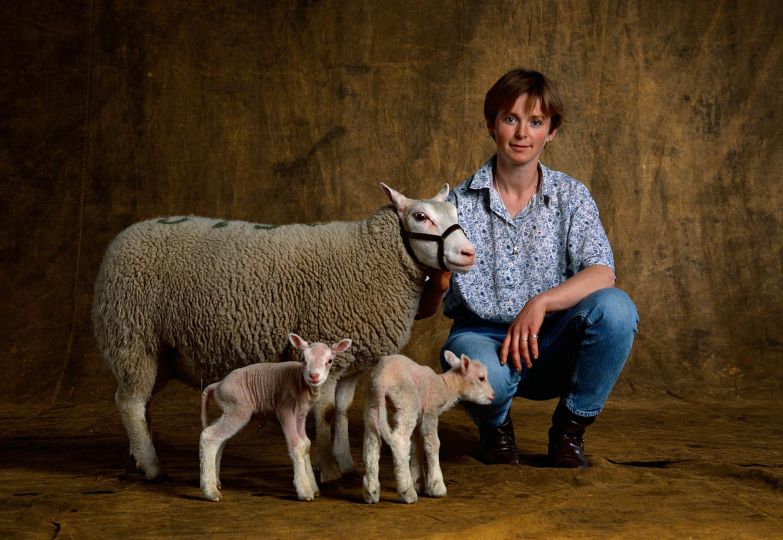

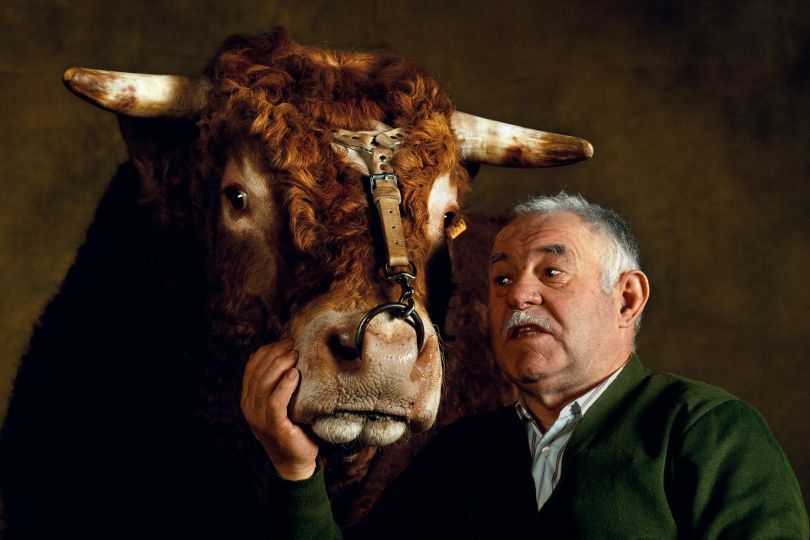

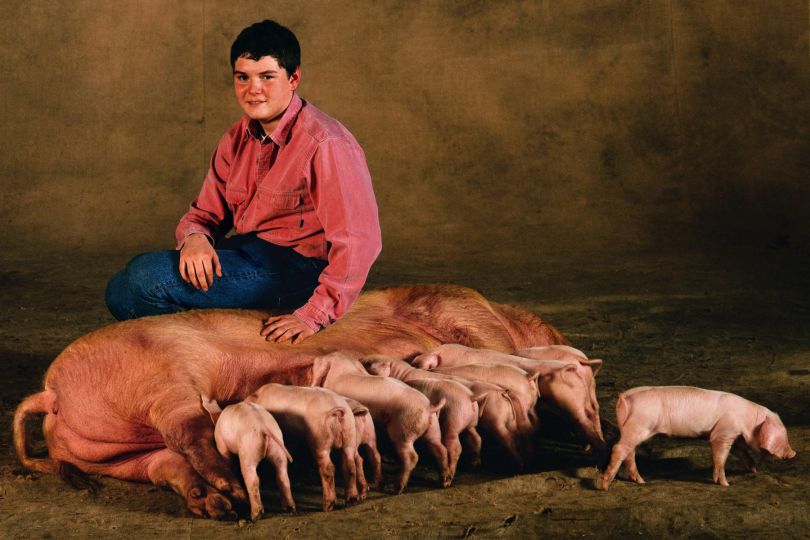

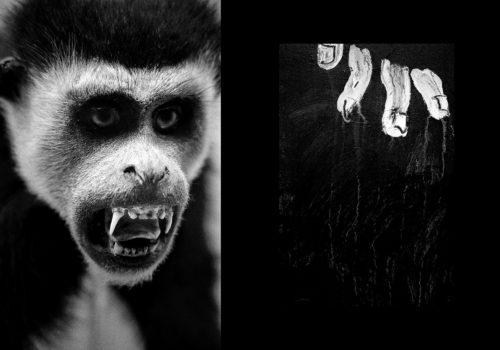

Before you see them all next week, let us highlight just two, each for a different reason. François Xavier Gbre is an Ivory Coast native and recent transplant to Bamako. He will be “the eye” of La Lettre, leading its readers through his large-format photographs taken with a view camera, in color, precise, frontal, peerless, taciturn and radical, like his two visions of an abandoned Bamako pool of which his are the only images. Not far from there, Daniel Naudet’s large-format photographs feature superb full-length portraits of animals. They are surprising, even magical. Bamako is full of animals, even in pictures.

Christian Caujolle