Whilst that answer may not be a lie, it is far from the answer I would give to an art critic back home in Amsterdam. To make sure Wang did not sent me straight back to the airport, I left out some essential parts: indeed, my work process resembles that of painting, yet I use photography and computer instead of oil paint and brushes. What I also did not tell Wang is that my work is often politically engaged and explores prejudices about social issues through playful and whimsical stories presented as fairytales.

An inspiration for my work comes from the work of the 19th century Dutch writer Eduard Douwes Dekker, especially Max Havelaar I read as a teenager. Knowing he was a distant family member through my grandfather, I valued all the more my emotional connection to this book and read it time after time. The way Dekker weaves and juxtaposes different visions of stories on the same subject would influence me greatly, which was later incorporated into my own style of storytelling.

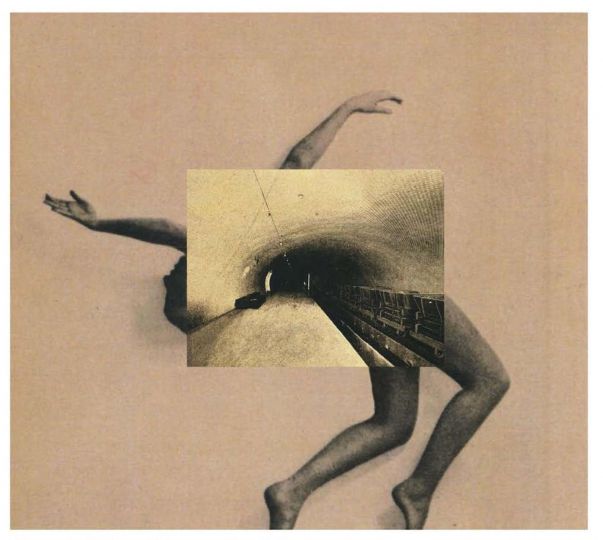

Upon graduating from the Academy of Art and Design St. Joost in Breda, I embarked upon exploring different cultures and societal landscapes. The travels took me to far corners of Asia, including South Korea, China and Vietnam. On magazine assignments, I travelled to cities like Las Vegas, Istanbul, Moscow and Dubai where I shot four stories in 2008. The topics ranged from sheiks’ daughters and their luxury teenage life in the upper echelon of Arab society (ELLEgirl) to a story about modern day slavery in labor camps full of immigrants (VICE), a heartbreaking contrast to say the least. Though my editors responded with great enthusiasm to these photographs, I felt dissatisfied with my images for they did not fully capture my true feelings about the subject. I wanted to depict my dreams and fantasies beyond just documenting images and developed a new procedure that could help convey the kind of narratives I wanted to express. I began using photo composites to combine the photographic reality with my own imagination.

In January 2012, I found myself in Ciego de Ávila, in the inlands of Cuba. There I came across illegal cockfights, which I had heard of and knew existed but had not yet seen professional photographs of it. My curiosity drove me towards the subject and I wondered how it would make me feel to witness such a game. Gambling makes these cockfights illegal since the Cultural Revolution in 1959. While a version for tourists remains legal without the gambling, illegal fights continue in utter secrecy as a way to earn extra income under a communist regime despite risking imprisonment of up to twenty years. To look for an illegal fight, I went into the slums of Santa Clara and found a broker to take me to a game. After traveling for hours into the absolute middle of nowhere on a horse carriage and cars, I realized I must convince these cockfighters of my genuine interest in their story. There was no room left for prejudices. They must trust me, so I must meet them with an open mind.

Cheering at the winning rooster, I found myself drinking home-distilled rum with crooks and criminals , becoming part of their world in a week. In a make-shift studio in the backyard of a rooster breeder, I created a scene using the cockfighters portraying the irony of the situation in reverse. This time the testosterone-filled audience fights each other. While the roosters watch them in awe; they raise the question, ‘who are the real cocks here’?

This experience in Cuba became Fijne Hanen/Gallo Fino, a body of works that shows a whimsical hyper-reality, a common thread throughout my work. My pink-hued, girlish fantasy of the world continued to collide and merge with my more skeptical and socially engaged views.

For the past few years I worked on projects discussing the notion of femininity and strength, including Russian women , I presented conflicting stereotypes about women. The project morphed into a fashion protest held on the Amsterdam canals during the Floating Fashion Week. Creating reversals of reality both in Fijne Hanen/Gallo Fino and Russian Women, I played with my own prejudices.

My current project is North Korea, a Life between Propaganda and Reality, in which I reconsider my own presumptions about the most isolated country in the word. I travelled 2,500 kilometers and saw cities with no light, sat at a table in an empty restaurant and looked at the yellow goo dripping from the tap in a fancy hotel foreigners like me were put to stay in.

During the government-controlled tour, my guides could not hide the poverty and extreme inequality. Through the window of the van, I could catch a glimpse of North Korea’s reality. Once in a while I saw men lying on the asphalted road to keep themselves warm and saw kids collecting acorns, digging for roots and fishing with their hand-made rods. Then I would see a bunch of well-fed, smiling kids surrounding the great leader Kim Il-sung on a propaganda painting, a stark contrast to the daily life of North Korea.

Propaganda persists as an essence of North Korea’s outward existence; it reflects the dream, the hope against a brutal reality, often bitter and harsh. In North Korea, a Life between Propaganda and Reality, I try to reconcile the image I was led to believe with the grim reality I encountered by creating a new propaganda.

Alice Wielinga