Observing that the internet envelops our lives is such a commonplace that it’s boring to have it repeated. Yet for something so omnipresent, relatively little is generally known about its physical location. It is not immediately obvious what photographs of the internet in situ would look like or where they would be taken.

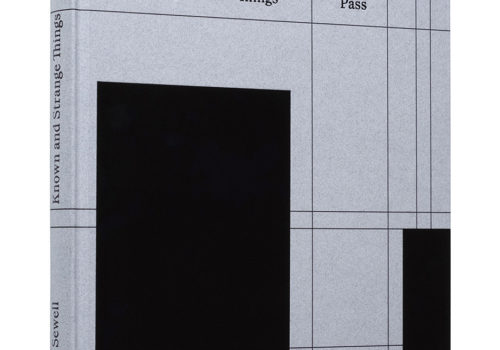

Cyberspace is both notional and real: a metaphor for the sense of somewhere we go when browsing, searching and clicking but also a place where real-world communications and decisions occur. We imagine it as far up in space – hence that other popular metaphor that is reached for, the cloud – when actually it is a long way down, at the bottom of the sea. Reaching an internet site for a user depends on fibre cables, transmitting quintillions of binary digits, inside submarine tubes that have been laid along ocean seabeds. In Known and Strange Things Pass, Andy Sewell sets out to photograph this peculiar state of affairs, one involving the imaginary and the real.

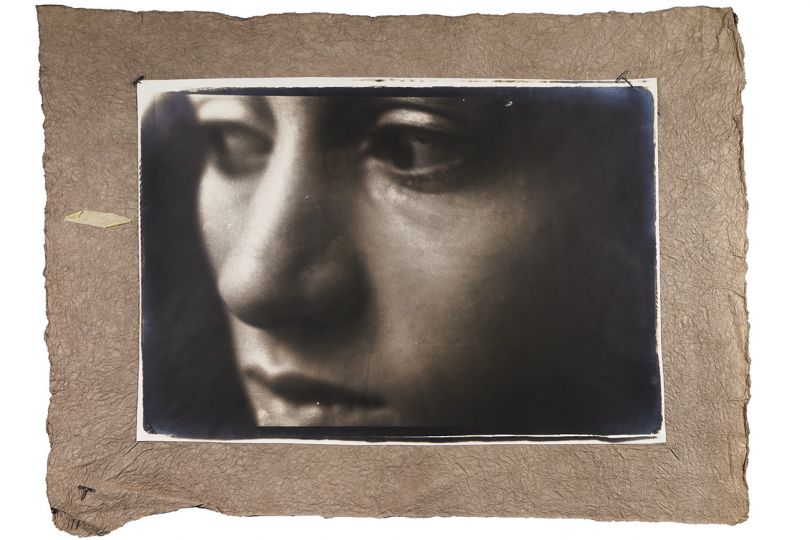

Since Nicéphore Niépce’s View from the Window at Le Gras was taken in the 1820s, photography has been bound up with the transformation of spaces into places. Spatial geometries became invested with aesthetic considerations and responses to photographs took on more psychological than phenomenological weight: more affect than thing. How to photograph something as solidly physical and processual as the internet without abandoning human interest is the challenge facing Andy Sewell.

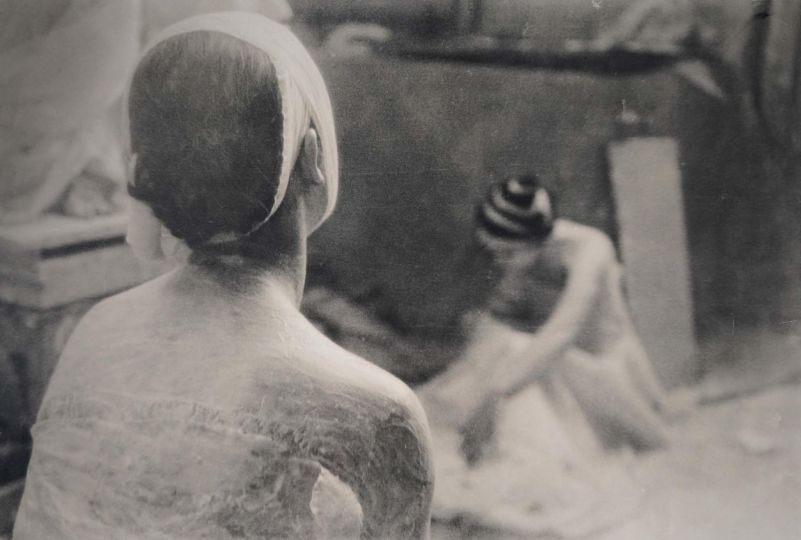

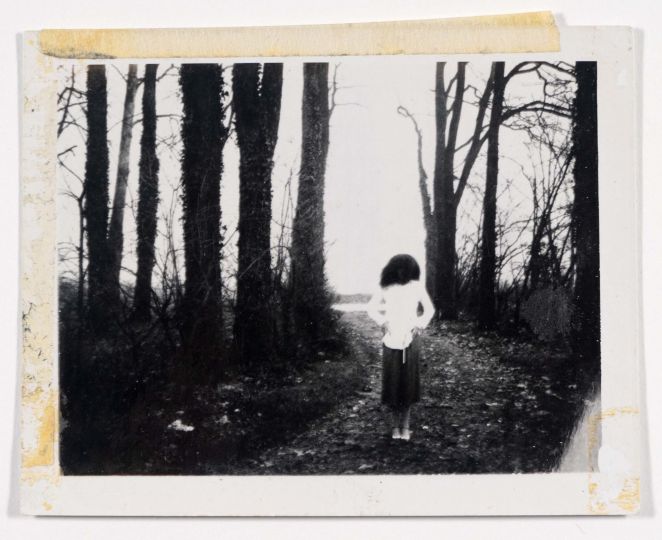

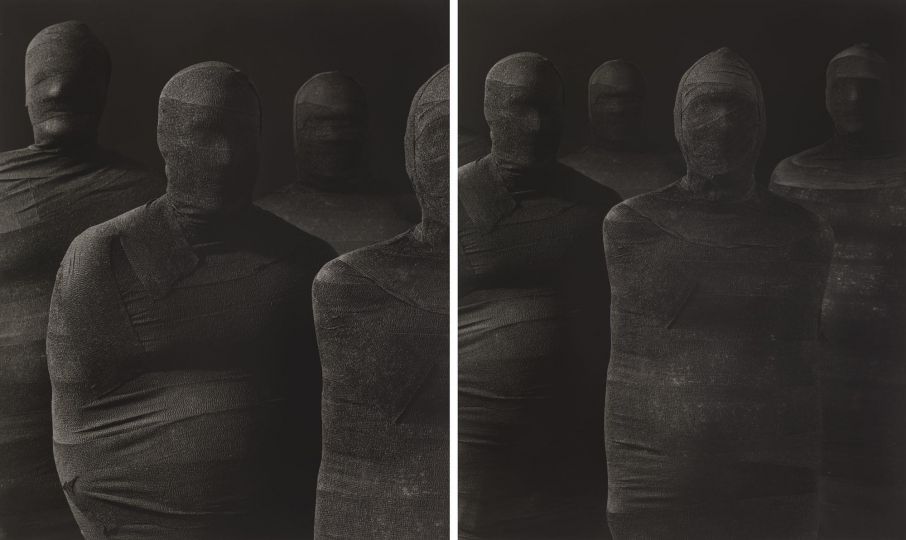

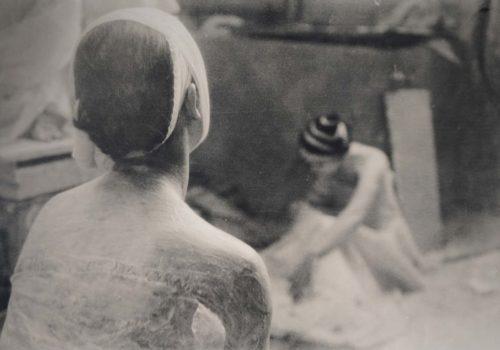

He takes pictures of junction boxes on dry land, either side of the Atlantic Ocean, where fibre optic cables begin their underwater journeys connecting Europe and America. Wires wrapped in insulating material are seen disappearing behind plasterboard encasements or filling storage cabinets like spilled spaghetti; cables are fed into solid-looking walls, the cavities around them protected with concrete; magnifying eyepieces are used by technicians inspecting connections. Photographs like these, always in black and white, punctuate Known and Strange Things Pass as clinical representation of functionalities and they are outnumbered by colour images presenting livelier scenes.

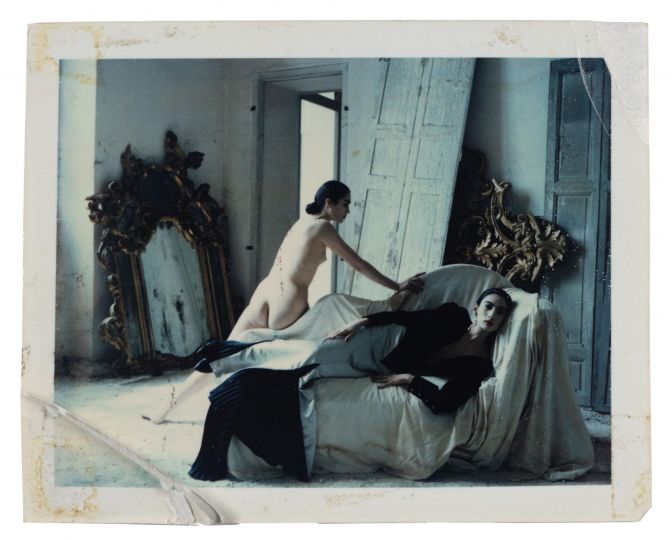

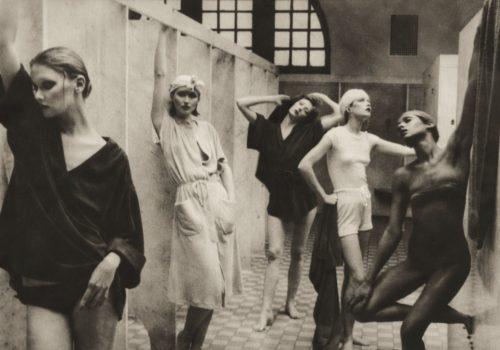

Rocky and sandy shorelines, washed by cerulean seas and surging waves of white water, look like holiday snaps; children play with wet sand and seashells; beach paraphernalia is glimpsed as the eye follows ocean contours. Impressions recorded in sand – a footprint and squiggly lines – are markers of human and crustacean odysseys which take on a hieroglyphic appearance: visual reminders of the complex journeys that are simultaneously occurring at incredibly faster speeds below the surface.

Known and Strange Things Pass is a work of conceptual photography and it asks the viewer to make cognitive links between the images. The pictures do not stand alone, open to being read in their own right, but have to be connected to one another to convey an idea. The notion being expressed is stated by Eugenie Shinkle in the essay that accompanies the book: “It’s about the immediacy of touch and the commonplace miracle of action at a distance; the porosity of the boundaries that hold things apart, and the fragility of the bonds that lock them together. It’s about a reality in which everyday existence is shored up by an immense, labyrinthine instrument devised by us, but grown into something that we no longer fully understand.” It has been called, glibly in the eyes of some, the digital sublime.

Conceptual photography lends itself to parable. The mechanics of the internet are rendered as dull schematics in greyscale whereas the lived richness of what they afford is conveyed through lively and colourful images. The corporeal, and the moving, elemental substance – water – through which continents are connected at lightning speeds, are tangible; the digital sublime is beyond representation.

Turning the book’s pages, non-digitally scrolling through different images, becomes a story that tells its tale through visual tropes of surface and depth. And like any good story, like the hyperobject that is the internet itself, it draws on imagination as well as reality.