IRRAWADDY FERRIES

10 dead in 2012, 50 dead in 2015, 72 dead in 2016, almost every year Burma records shipwrecks of ferries on its great Irrawaddy river and its tributaries.

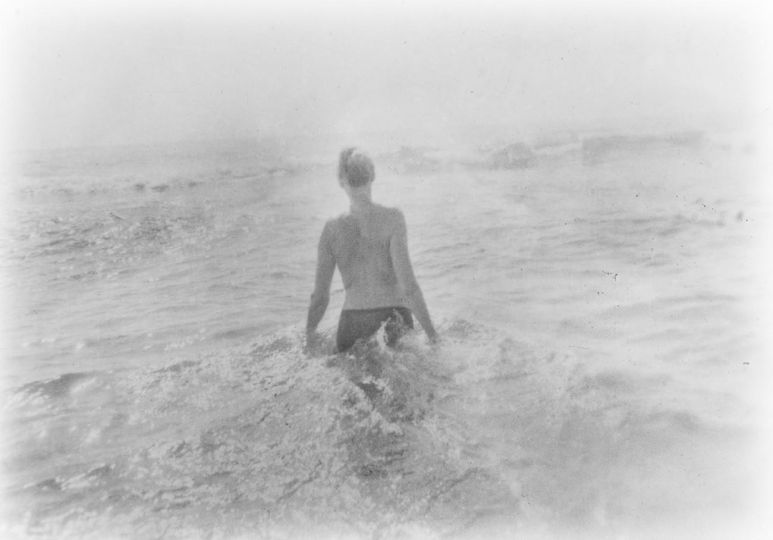

To get a more precise idea of the situation, I decided to embark on March 3, 2017 aboard one of these old local ferries, leaving from the port of Rangoon to reach, after 2 days of crossing, the small town of Labutta located in the vast Irrawaddy Delta.

My objective was to make a photographic and documented report on these boats of another age and in particular on the living conditions of the Burmese using this means of transport or working there. The ferry, even if the travel time is very long, is in fact the transport favored by the most disadvantaged, because it is much more economical than the bus.

Most often of Chinese origin, these ferries are well over the age of 50.

Old, rusty, poorly equipped, poorly lit for night navigation, made perilous because many boats that circulate on the river have no light, these boats do not inspire confidence.

On Burmese ferries, priority is given above all to the transport of goods and, most of the time, no space is provided for passengers. From the stairs to the various decks and corridors, all areas of the boat are cluttered with a wide variety of packages and products. The number and volume of goods is such that the Burmese have no other solution than to travel on the ground, putting up mats or blankets, and to lie down tightly against each other. Some have no choice but to lie down on plastic bundles or cardboard boxes stacked in the corridors or corners of the ship.

Loaded to the brim, the ship leaves the port of Rangoon with more than 150 tonnes of cargo, all loaded by hand by porters; mechanization does not exist for this type of ferry. Only container ships are loaded by cranes.

Some of the porters are employees of the company Inland Water Transport (ITW) which belongs to the Ministry of Transport, others are simply paid by the task at this destination. It is a real slave labor for the carriers. These are not paid by the number of goods they transport, but by weight! They can support on their shoulders loads up to 95 kg for the strongest and the bravest!

Each unloading takes place in perilous conditions; porters must indeed take narrow and rickety wooden footbridges spanning the shore, at the risk of falling. The heat in the hold where most of the cargo is stored is overwhelming and there is no safety on the boat.

In April 2017, one month after my report, a new shipwreck took place, killing around thirty people.

Alan Dub