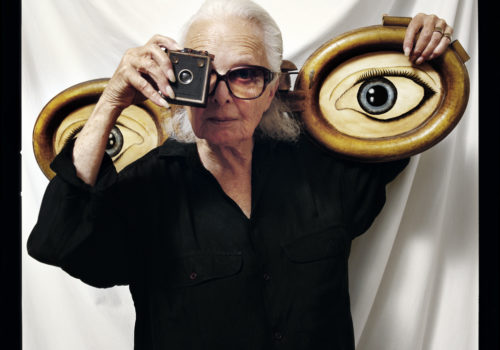

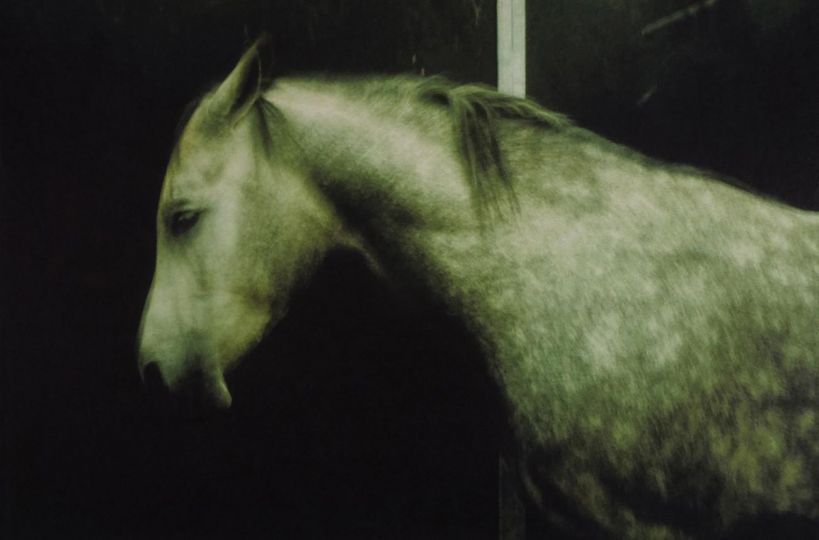

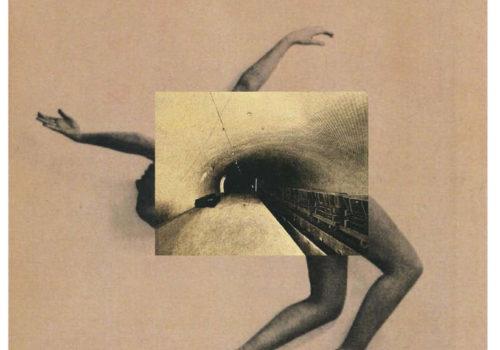

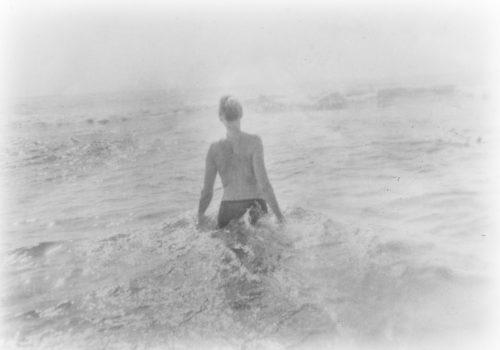

We overlooked one of the most important photography books of last year: Abe Frajndlich’s Penelope’s Hungry Eyes, published by Lothar Schirmer:

The genesis of this book goes back to when I arrived at Minor White’s house for a live-in workshop in the fall of 1970 and my first task was to organize his photography library. As I took one book after another up to my third floor room, I was mesmerized every night by the plethora of unforgettable images. That was when I learned that photography had a relatively short history, and besides the incredible icons in that history, I was struck by the fact that most of the practitioners were anonymous and unknown except to a miniscule circle. Unconsciously I must have started to dream of changing that fact, and widening that circle. More than four decades later, you are holding the fruition of that dream in your hands.