Yoram Roth is the kind of person you rarely find in Berlin. Though Berlin-born (1968), he was raised in New York, where he acquired and honed his unique personality and cosmopolitan charm. In the city that never sleeps, he completed his photography studies at Fordham University in 1990 and moved back to his hometown in 2007. Only then did Roth start to commit to fine art photography. Today his own photographic work is handled by CAMERA WORK and has been shown internationally. The father of three sons splits the rest of his time between building a photography collection and leading a business in the photographic art world.

During the corona lock down, I spoke to this charming maker & shaker about his latest venture: the global development of Fotografiska along with its recent and upcoming subsidiaries. While you hopefully continue to stay at home, enjoy this in-depth interview that reveals “what’s new” with Yoram Roth.

Nadine Dinter : For many years, you have been deeply involved in photography: you’re an artist, a collector, and the chairman of the board and majority owner of the renowned Fotografiska museum. Tell us a bit more about how you juggle those three roles and where one starts and the other one ends.

Yoram Roth : Well, I can’t say I’m really succeeding at juggling. After years of working as a photographic artist I’ve scaled back my work. I’ve given up my studio in Berlin, and spend most of my time working these days. I travel a lot. Last year I was in the US and in China at least six times each, not to mention time spent in various European cities. Most of this is about Fotografiska, but I also attend all the major fairs. Unfortunately I am no longer at the fairs as an artist, but primarily to meet with other artists or their gallerists and managers about shows at the museums. I’m holding on to this idea that I will return to art as a form of early retirement, but that seems far away right now.

ND : With your gallery representation through Camera Work, your work was shown world-wide. What was the top-selling country? And which market, on the other hand, turned out to be difficult for nude photography?

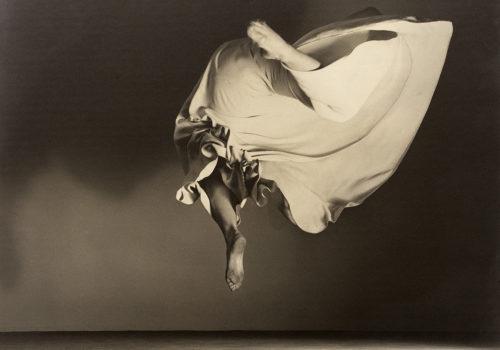

YR : Having a major gallery like CAMERA WORK championing me as an artist was certainly an advantage, and offered great insight into how the market works. But ultimately it’s disappointing. The whole world has gotten more conservative, and nudity is thought of as disreputable these days. Although my work is about abstraction and the ethereal aspects of the human figure, there’s a large contingent of people who can’t look beyond the nudity. I was disinvited from Photofair San Francisco last year. I had to be selective in the work I brought to Photofair Shanghai, and wasn’t even able to show my website in Dubai, never mind my actual artwork. I’m especially proud of being European in that context. I’m aware I’m a middle-aged cisgender male shooting more female than male bodies, which makes it a particularly difficult path to navigate. In San Francisco my work was perceived as politically incorrect, whereas in the emirate it was simply considered porn. It’s neither, but artists are rarely given the opportunity to explain their work.

ND : Having studied photography, does this enable you to see, perceive, and judge the art of fellow photographers in a different manner?

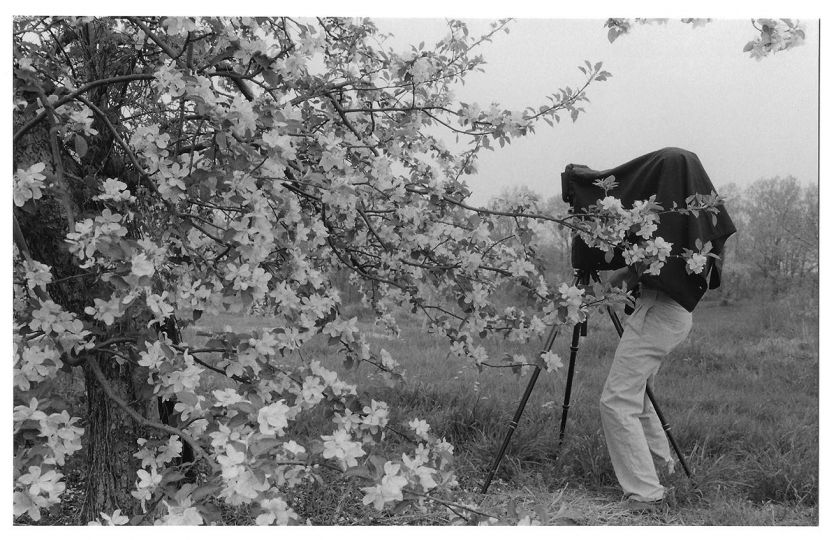

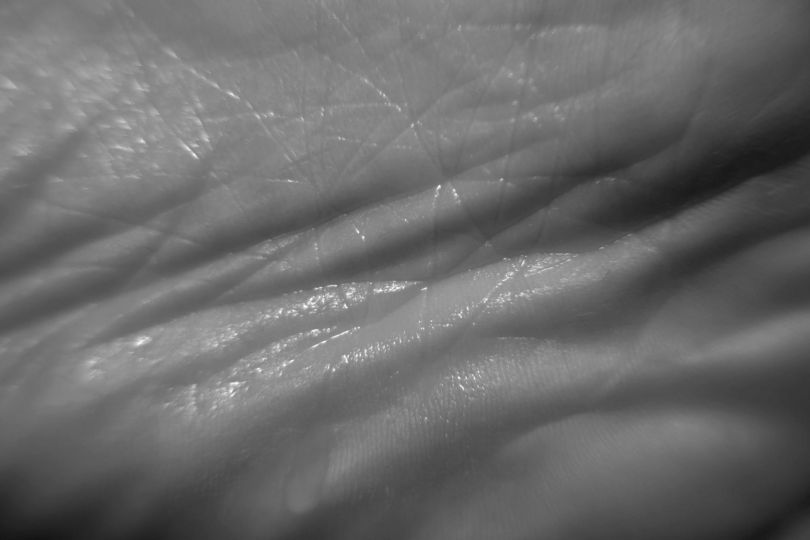

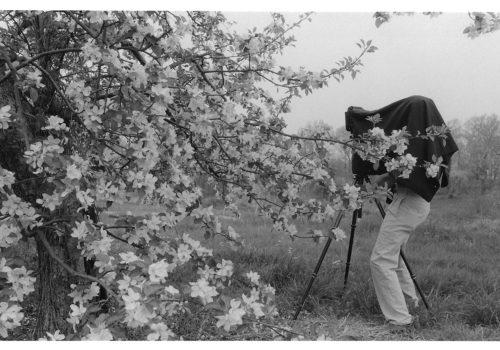

YR : Absolutely, though I try to stay aware of my own biases. I studied under Larry Fink in New York in the late 1980s. At the time one of his projects was very much about hands, which resonated with me. Like anyone else my tastes change over time, influenced by what I see. I just get to see so much more than most people because I’m so deeply involved with photography. There’s definitely a wide range of styles amongst incredibly skilled artists, but I don’t automatically like it simply because it’s good. Separating one’s own taste from the task at hand is important. My collection is very focused. When it comes to selecting work for us to show at Fotografiska it’s the responsibility of the curatorial committee, whose members come from a wide array of experiences and backgrounds. It makes for spirited conversations, but the decisions are not about collectability, though definitely informed by every member’s personal tastes.

ND : In your own photographic world, you have looked for and found inspiration in the world of art history. With series like “Personal Disclosure”, “Brutalism”, and “Spatial Concepts” you have been referencing the Spanish Baroque, the architecture of the former Eastern part of Berlin, or Italian Spatialists like Scheggi, Bonalumi, and Fontana. What drew you to those particular topics?

YR : These ideas take a long time to gestate. I know how I got there on each project, and why I chose to follow an idea to its logical conclusion. There are a lot of other ideas that didn’t work, or that I am holding on to for future projects. It would take me hours for each project to explain it, so the short version will have to do. “Personal Disclosure” was very much about the sanctity of the human body, and it made sense to borrow the visual language of what was largely religious iconography. “Brutalism” was about the perseverance of the self within a system tasked with putting the collective good above that of the individual. “Spatial Concepts” was about capturing light within the physicality of the final work, and to push through the actual print. In that way it was exactly like what those artists were doing in the 1960s, except that I built it around photography, rather than painting. All of my work is made up of unique pieces, I don’t do editions. Every piece is made of several layers of photographic paper, of steel, and acrylic. Go check out my website if you want to understand that better.

ND : Beside your own art creation, you have been collecting photography for many years. Whose work is part of your collection?

YR : The emphasis of the collection is on work that originates as photography, but then has a degree of physical execution to it. It’s very much the same approach I seek in my own work: I collect unique pieces that go beyond the printed image. There are so many great artists working this way: Peter Beard, Douglas Gordon, Mickalene Thomas, Kyle Meyer, Annegret Soltau, Ulla Jokisalo, Cooper & Gorfer, Christiane Feser, Tawny Chatmon, Tina Berning… it’s a pretty specific collection. I also collect some staged photography, including works by established artists like David LaChapelle, Marilyn Minter, or Sandy Skoglund, but also emerging talents such a Julie Blackmon, Maisie Cousin, or Anja Niemi.

ND : Plus, you have been supporting photographic/art institutions such as C/O Berlin as a major patron. Did you learn the importance of philanthropy back in New York, where you grew up? How do you feel about the lack of charitable patronage in Germany, compared to the US?

YR : I am very active in charity, though most it has been focused on immigrant inclusion issues, not so much on art. I actually think we need to find a new way of thinking about culture in Europe. The idea of working for profit is seen by some people as some kind of proof that you’re not serious about art. This attitude is tiresome, and destructive. In Germany, and specifically in Berlin, it means that the same places get all the funding, often tied to their ability to relentlessly network with certain cultural city officials, while their offering is very precious in a navel-gazing sort of way. What I respect so much about C/O Berlin is that they are trying to find a way that stands on its own feet. The shows are great, and that helps draw a large and curious audience. In general there is an expectation that the government should fund cultural activity, whereas in the US there’s a much bigger participation by private individuals who support the arts. That is largely absent in Europe, and it’s a shame. A greater tax deduction for charitable giving would set off a whole wave of good efforts.

ND : You have dedicated most of your time to building up the global network of the highly-respected Fotografiska museum, with recent openings in New York and Tallinn. Founded in 2010 in Stockholm, this innovative and spirited museum concept has been raved about by its audience ever since it opened. What’s the secret of its success and how do they operate compared to other museums?

YR : Fotografiska is all about inclusion. A lot of museums and other art institutions insist on a certain air of importance. As a visitor you’re left with the sense that you should be amazed in hushed quiet tones, and any questions you might have about the art are proof that you just don’t get it, and don’t really belong. We make art accessible. Photography isn’t intimidating, everyone feels comfortable having an opinion. Also, people really appreciate a good photograph these days. When smart phones with cameras became ubiquitous ten years ago everyone declared it the death of photography. It has certainly had an effect on photojournalism, but in general there’s a much greater appreciation for a good image, in part because everyone now has thousands of crappy shots on their digital camera roll. People have come to realize that it takes more than a clever button combination to make a good photograph. The artist must have skills, and a point of view, and a unique approach.

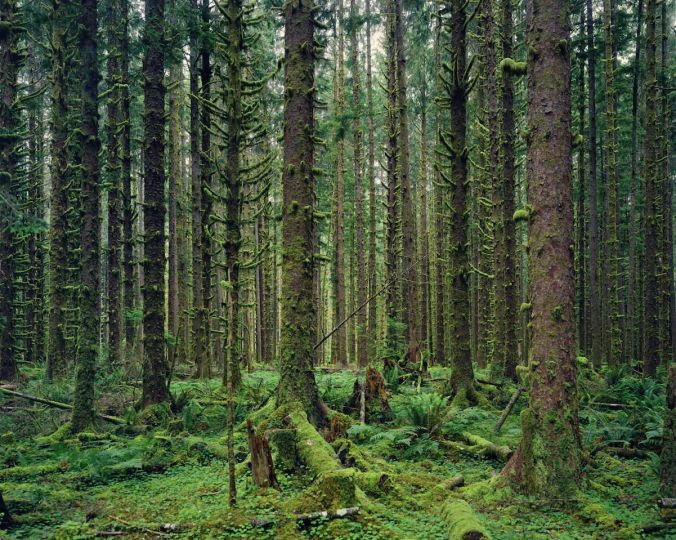

We have built our business on the foundation of photography and the trust of the creative community. We showcase the greatest photographers, whether they’re just emerging artists, or already famous internationally. Fotografiska shows everything from fine art to pop culture, landscapes, people, staged, or fashion photography. Our shows are developed directly with the artists, or curated around a central theme. We operate large, modern exhibition spaces, featuring several photography shows concurrently, meaning we usually have four or five different shows on view per museum. But we are not a collecting museum, nor are we a gallery. That means we don’t buy art, and we don’t sell it. Instead we work directly with the artists, galleries, estates, and private collections. We have run more than 200 successful shows over the last ten years.

Equally important is the experience around the photography. We offer our community of members a huge amount of programming, from artist talks and workshops to DJ nights and intimate concerts. There’s something special going on every day. A Fotografiska museum has a great restaurant and bar, because that is still central to how we spend time with our friends and loved ones. Our museums are open till 11 PM or later every day, and you can roam our exhibits with a glass of wine in hand, or just join the fun in our event spaces. The simple but difficult goal is to reinvent the museum for the next generation. It can’t just be white walls with art hanging and small info boards, that’s just not enough anymore.

ND : Which cities are next on the agenda?

YR : We have a lot of exciting conversations, but these are not overnight pop-ups. It takes at least two years from introduction to opening. We are evaluating opportunities in Berlin and Copenhagen, but also Lisbon, Toronto, Shanghai, Beijing, and Istanbul. There are so many cities where a Fotografiska could work, but we can’t do them all. As an art venture we have to move slower than some normal businesses.

ND : Has Covid-19 affected Fotografiska?

YR : Of course. Cultural businesses are probably the hardest hit of all. We are not a large industry that the finance world considers mission-critical. There’s not a lot of support in most countries for cultural entrepreneurialism. It’s been extremely difficult. We had to take drastic actions to preserve cash, thus ensuring our ability to start back up as soon as we are allowed to. But at least we have a strong community that trusts us, so we have launched a number of shelter-at-home photo projects. Take a look at our New York Fotografiska Instagram feed, or the hashtag #fotophoto. I hope a year from now we all look back in astonishment at what we had to endure.

ND : Any advice for other people who would like to invest in photography/arts and don’t have any experience yet?

YR : Look at as much art and photography as you can; your eye and understanding and taste will develop over time and exposure and experience. Don’t approach it as some kind of business venture. Ultimately, you have to live with it, so make sure you like what you collect. Try to get to know the artists, and support them and their galleries as they grow. Artists and their works have a point of view; think about what the collection says as a whole. Collecting is about being part of a community and communicating. Art matters, and art requires all of us to participate.

Follow Yoram on Instagram at: @yoram_roth or add him on Facebook or LinkedIn