Thorsten Wulff is an absolute matchmaker. Not sure which year we met exactly, but it’s been a few years down the road already. When it comes to photography, what never fails to impress me are the wide variety of cameras, techniques, and places that Wulff masters in his work.

Analogue, digital, darkroom, on location, on site – he does it all. Pair that with his gentle nature, large network, and skill at making everyone feel at ease – even with a photo slot of just five minutes and surrounded by a raucous crowd – makes him a photographer to remember.

While shuttling between a photo job in the UK, documenting the latest theater plays in Karlsruhe, and setting up his latest shows in Lübeck, he took the time to sit down with me and share how he sees + lives photography. And, of course, about what’s new.

Nadine Dinter: To me, you are a multitalented matchmaker, switching between the roles of photographer, writer, and networker with ease. How would you describe yourself?

Thorsten Wulff: My friend, the graphic designer Erik Spiekermann, once compared me to a Swiss Army Knife. So yes, there is this communication toolset centered around photography. The secret of a good portrait IMHO is developing trust with your subject to show your good intentions – from a stranger on the street to the politician on his airplane or an actress on the red carpet. As you know, Greg Gorman was amazed by the amount of homework I did before meeting him. When I meet you to take your picture, I know where you stand on sanctions on Russia, have seen your last movie, and at least know what your last three books were about. The stranger on the street always gets my smile. In New York’s Chinatown, I discovered three Chinese ladies sitting in the sunset in 1987. I crouched in front of them with my Nikon F3 and 24mm and took the picture. One of them hit me with her cane, on the lens hood. I learned my lesson: Get close, and smile.

You are one of the classically trained photographers who learned to develop their photographs in the darkroom and know how to read the sun and when it’s time to use a digital camera instead. Do you miss the analogue days? What do you see as the advantages of using a digital camera?

TW: Working digitally is pure bliss. In 2001, I got my first digital camera, a Nikon Coolpix 995 with 3.3 megapixels. I started shooting magazine covers with it; the resolution, with a bit of tweaking in Photoshop, was just enough for a full DIN A4 page. Adobe Lightroom was next, and the workflow continually improved. In 2007, Nikon came out with the first full-frame DSLR, the D3, which I still use and love. Now we have the transition to mirrorless bodies, giving us pitch-perfect exposure previews in their electronic viewfinders, fault-free autofocus, and the best part: silence.

I just finished a highly rewarding project in Karlsruhe, Germany. For six weeks, I covered the backstage life at a major theater with a lot of different artistic environments. Most of the situations were impossible to shoot with a loud DSLR – imagine me standing amid 50 musicians taking pictures of the conductor without getting into trouble! On the other hand, I like to shoot personal projects analogue with my Nikon F3 and Ilford HP5 film. My friend Roland Franken runs the German pro magazine DIGIT, and the cover of the recent issue featured an image I shot on film, printed in my bathroom. The enlarger rests on the washing machine, the trays on the tub. Then there is a portrait project in 4×5 inches with a Plaubel monorail, which I use to get me out of my digital comfort zone. With the analogue renaissance in full swing, I expect to see some surprises this year, like new bodies by classic camera makers and new emulsions.

You have portrayed iconic figures like Günter Grass, Patti Smith, Salman Rushdie, and Steve Schapiro. What’s your secret to breaking the ice?

TW: I give them a box of marzipan first! But seriously, all you have to do is keep things at eye level. Grass, for example, despised people sucking up to him just because he was a Nobel laureate and all that. We first met in 1986, a night I remember well because I sat next to his wife, Ute, who was annoyed at my clicking camera. After five frames or so, she started hitting me in the ribs with her elbow for me to stop – which I did after I was satisfied, around frame 21. All his life, Grass allowed me to get very close. He was an amazing, very warm human being. Not really what you would expect from his public image. This image here (where he lights his pipe) was one of our last encounters before he died. He grabbed my shoulder and said: “Do your thing!” and I answered, “Sure. Light your pipe!” In general, I manage to put people at ease by being calm, well informed, and usually ready with a joke. In the case of John Irving, I learned after the fact that he is not really fond of photographers, when his publishing house Diogenes protested about the pictures. He was too kind to complain; in this image here, he joked about the quality of my English. Salman Rushdie called me the fastest photographer he ever met, which was a very kind compliment. Patti Smith shot me with her Polaroid shooting her friend, the writer Haruki Murakami. Later I took her portrait in the ladies’ room of Springer’s Berlin headquarters (I needed a white wall). And Steve Schapiro, who sadly just passed away, was one of the warmest and most authentic persons I ever met. The night of our first encounter was pretty busy: I was working with Rhea McCauley, the niece of Rosa Parks. Steve and I bonded instantly; it was amazing how friendly and open he was. It was only the next day that I found out who he was and what he did all his life – I was completely blown away! Not a lot of photographers with a tenth of his portfolio display such genuine interest and heartfelt modesty. Later we met again and had a shootout with our Nikons. Steve will always have a special place in my heart.

You were born in Lübeck but work Germany-wide, with some major photo jobs abroad. Looking back to when you started out in the business, how has the work of a photographer changed over time?

TW: That is a good question, Nadine. The city of Lübeck is full of history. Its role in the Hanseatic League, which was a kind of proto-EU, still leaves its traces across the continent and beyond. Then there are people from there like Thomas Mann and Willy Brandt, who shaped culture and politics in the last century. I’m a bit too young for Mann, but Brandt I met a couple of times and took pictures of him.

My general idea when starting out was to go out and tell the truth. Influenced by the German documentary photographers Thomas Hoepker and Robert Lebeck and the humanist core of their work, my goal was to build a career as a photojournalist as they had. To work for a magazine that sends you abroad with 300 rolls of film and 12 weeks’ time to come up with an exciting picture essay. Unfortunately, these jobs are not available anymore. Photography is still a force able to change the course of history. Just now [note: our conversation took place in early April 2022], the images from Bucha in Ukraine are having the same impact as those from My Lai 50 years ago. And just as the public opinion in the USA about Vietnam was changed, Olaf Scholz cannot just listen to German industry bosses greedy for Russian gas but has to act in the face of war crimes. Documented by photography. So, from my perspective as a photojournalist, nothing has changed regarding the moral duty of the job, especially facing Russian lies about fakes or Ukrainians killing their own people for western cameras. Grab a camera, go out there, and tell the truth. In my view, that’s the highest goal of photography.

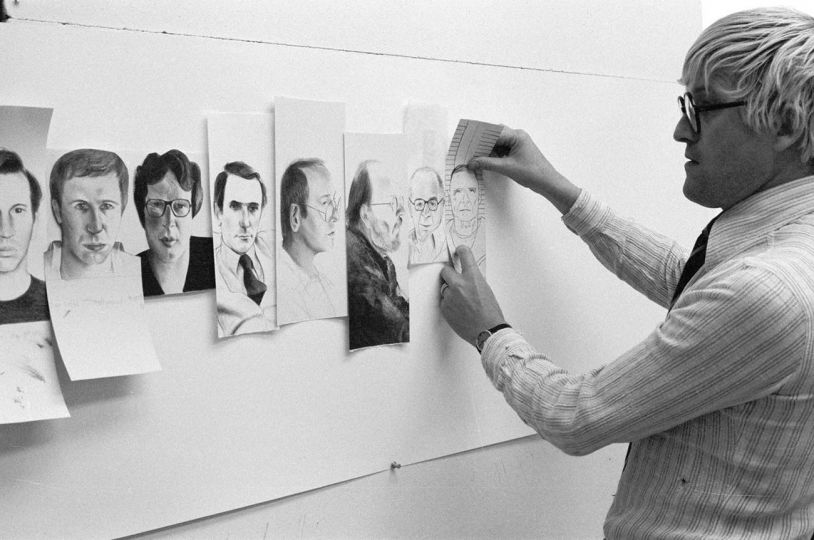

A considerable part of your work is devoted to Günter Grass, with many of your photographs now on permanent display at the Günter Grass House in Lübeck. Tell us about how you met, how long you worked together, and your take on this literary figure.

TW: My good friend Jörg-Phillip Thomsa, born like me on May the 4th, does an amazing job running the Günter Grass Haus museum in Lübeck. He just overhauled the exhibit, displaying lots of images I took over the last years of the writer’s life. There is a cluster of frames that shows all the guests visiting Grass throughout the years – old friends and colleagues like Cornelia Funcke and Salman Rushdie, diplomats, musicians, and journalists. Grass basically knew everybody, and they liked to stop by in Lübeck. Usually, those visits gave way to a small party at Hilke Ohsoling’s (Grass’s longtime assistant) cozy second-floor office. You would sit down with Grass and his friends at a huge wooden table full of wine glasses, talking world politics. His voice in German public debate is painfully missing, especially today.

One of my most iconic images is Grass smoking a cigarillo on a very hot, dog-day afternoon in August 2013.

Grass and his wife lived in Behlendorf, in the countryside, in a lovely house with an attached shed for the writer’s etching and sculpting activities. One famous Grass quote is, “das Glück ist eine Fundsache” – happiness is a found property.

In photography, you know when you capture something really special. Grass stepped out for a short break from writing his book Hundejahre (Dog Years, 1963) and a sip of water. He smiled at me and lit a cigarillo. I snapped a couple of frames with the Nikon D3 and my 85/1.4 wide open. It was a brief moment, just one breath of smoke. But I knew I captured history. Another image very dear to me is of Ute and Günter Grass leaving the museum, walking side by side. Grass had no driver’s license, so his wife drove him everywhere in her Volvo. They were a very loving, symbiotic couple. And while I was on first name base with him, she always remained Frau Grass to me, going back to her elbow in my ribs for shooting too many pictures of her husband.

What other artists resonate in your work?

TW: A major influence early on in my life was Stanley Kubrick. Long before I learned that he started out as a photographer, I was a big fan of his films, especially 2001: A Space Odyssee. His use of available light, like shooting Barry Lyndon by candlelight in 1975, always amazed me. Stanley died in 1999 and is buried in his own backyard, surrounded by his favorite trees. I visited his wife Christiane in 2014 at their home in England for a long chat. Being a photographer gives you the opportunity to go boldly where few have gone before and meet people who are otherwise not so easy to meet. German actor Hardy Krüger told me about how he worked with Jimmy Stewart (in the film Flight of the Phoenix, 1965), John Wayne (Hatari!, 1962) and, yes, lit by candles with Kubrick. A real gem was the actress Christine Kaufmann. I met her for five minutes to take her portrait in a dressing room, and it became almost two hours. Kaufmann was married to Tony Curtis in the 1960s and told me all about Hollywood in those days. I was painfully aware of never being able to memorize all the details and anecdotes and that a tape recorder would have turned the conversation into a book. She was a close friend of Yul Brynner, a very active photographer himself next to his acting career. Life as a photographer rewards you with unforgettable, surprise encounters.

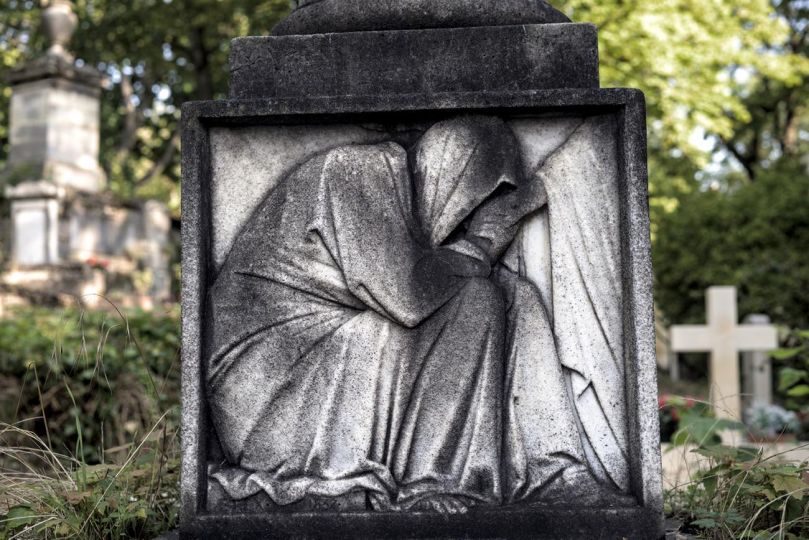

Your work will also be presented at another fascinating location in Lübeck: the columbarium at Die Eiche. What is that show about?

TW: That is right. The former granary of Thomas and Heinrich Mann’s family at Lübeck’s harbor has been revived as an inner-city cemetery. Though it has kept its old name Die Eiche (The Oak), it has been totally refurbished inside. The term columbarium stems from the Latin word for dove, columba, and basically means dovecote.

People will be placed to their final rest in funerary urns behind cabinet doors fashioned by various artists. I was invited to design one of the areas, a room for about 200 urns. My partner Nadja and I went to shoot rustic doors in the Belgian city of Liège and in Brittany for the cabinet fronts, which act as a placeholder. Usually, people buy a columbarium niche while the person is still alive – an option there is to have me take your portrait. This is something I want to do with the 4×5 monorail and print the final image with the durable platinum-palladium technique. This way, the eternal character of the portrait is captured more enduringly than using digital technology. A platinotype can last thousands of years, which fits the issue.

Besides classic portraiture jobs, you work a lot for theater companies. How did this come about, and what’s your latest collaboration?

TW: I love theater and the timeless value of Shakespeare’s plays. A backstage image I took of my friend Andreas Hutzel is displayed in Shakespeare’s Globe in London; director Roger Spottiswoode named it Acting per se.

I prefer to be as close as possible to the actors and shoot the events on stage like something happening in the real world. One of the places that allow me this approach is the Globe Berlin.

As a facsimile of the London original, the theater (still under construction) has a wooden oval of varying height that serves as the stage. There is no railing, so you end up on your nose if you misstep. This makes shooting drama highly exciting – while Romeo and Tybalt cross blades, you have to mind your feet. The Globe is an excellent opportunity to be in the thick of things and enjoy the classics. I already mentioned Karlsruhe above, where I shoot the productions of my friend Anna Bergmann. With her dramaturge Anna Haas she creates incredible contemporary theater. The two of them, and importantly, the actors, trust me enough to let me shoot rehearsals with them on stage. This is as good as it gets.

You recently traveled to England for a special project – what was it about?

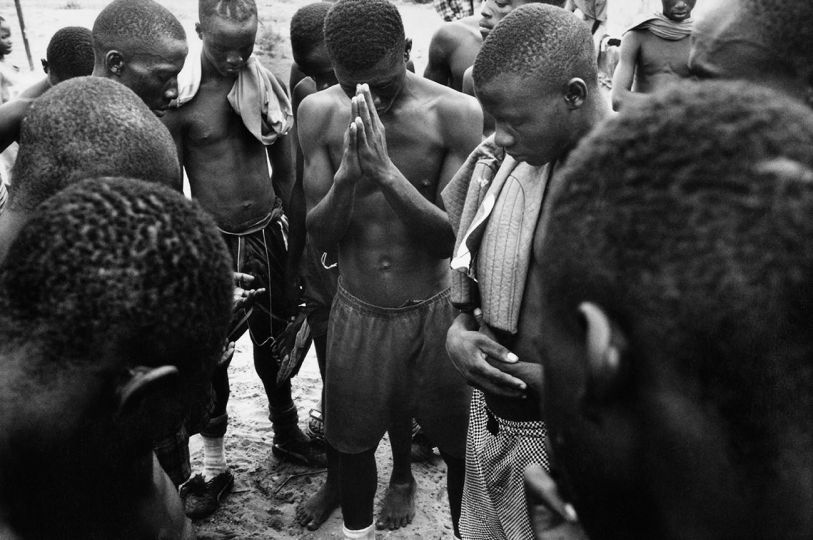

TW: Nadja and I went to England to visit Magnum photographer Ian Berry and his wife. Berry was hired into Magnum by Henri Cartier-Bresson himself, HCB checking the contact sheets in a bistro in Paris and all. I was excited to show him my series The Irish from 1988. To my pleasure, Ian picked two of my prints to have framed. We talked a lot about the state of photojournalism in the modern world and gossiped about Magnum.

All in all, I feel quite happy with how my life with the craft of photography turned out. After 40 years, many things, like my relationship with Thomas Hoepker, have come full circle. Of course, I would love a phone call from Stern magazine asking me to spend a couple of weeks with Vitali Klitschko and Volodymyr Zelenskyy in Kyiv with 30 rolls of film.

Your advice for the next generation of portrait photographers?

TW: Do your homework and be kind. Remove their fear.

Be quick and finish before people get bored with you and the setup.

And don’t talk too much.

Curious about more? Follow Thorsten Wulff on Instagram at @herrwulff, and check out his website https://thorstenwulff.com/

Also, make sure to check out his latest shows:

Günter Grass-Haus, Glockengiesserstrasse 21, 23552 Lübeck, Germany.

https://grass-haus.de/

Open Monday to Sunday, 10 am to 5 pm

Die Eiche, An der Untertrave 34, 23552 Lübeck, Germany

https://die-eiche.de/

Guided Tours Monday to Friday at noon