An appreciation of Helga Paris’s photography reached a wider audience than ever before with a 2019 major retrospective in Berlin, the city where she lived and worked. An exhibition at Kicken Berlin at the end of the following year confirmed the realization that Helga Paris’s work was of considerable and intrinsic interest. Now, two books of her portrait photography in the German Democratic Republic (GDR) make clear that the enduring quality of her achievement goes beyond the merely documentary.

The workplace in Women At Work is a textile factory that Paris first became acquainted with during an internship there as part of her fashion design studies in Berlin. Returning there as a photographer (some of the women knew her from her internship), she was able to establish a rapport with the women in ways that bring to mind Tom Wood’s amity with the people of Merseyside. The ability of both photographers to engage empathically with their subject matter accounts for the quality of their work.

Paris describes how she took the photos in the clothing factory: ‘I asked them to stand or sit somewhere, told them I didn’t expect anything special; they should be as they saw fit. It just had to be quick so they didn’t pose for the camera. Before they thought about how do I look, the shutter was already pressed’. The result, a remarkable series of pictures, conveys their sense of self-identity and quietude. A degree of formality and restraint arises from the workplace’s environment and there are consequent similarities in dress but, like the school setting in Vanessa Winship’s portraits of schoolgirls, the situation does not define the individuals. Paris’s pictures create a caesura in the industrial system structuring the women’s working lives and a kernel of their being possesses the space. They don’t own the means of production but Marx would be pleased to see that they have loosened their chains.

The women inhabit a mental landscape that has little in common with the louche woman in the song by the Rolling Stones, ‘Factory Girl’. In that song the woman’s attributes are itemized with devil-may-care nonchalance while those who pose before Helga Paris’s camera are sufficient unto themselves. What comes across is the absence of any felt need for shows of errant individualism but an equally strong feeling that their equipoise and mystery cannot be mistaken for resignation. The women present themselves and ask nothing in return: in the face, writes Levinas, ‘the other appears to me not as an obstacle, not as a menace I evaluate, but as what measures me.’

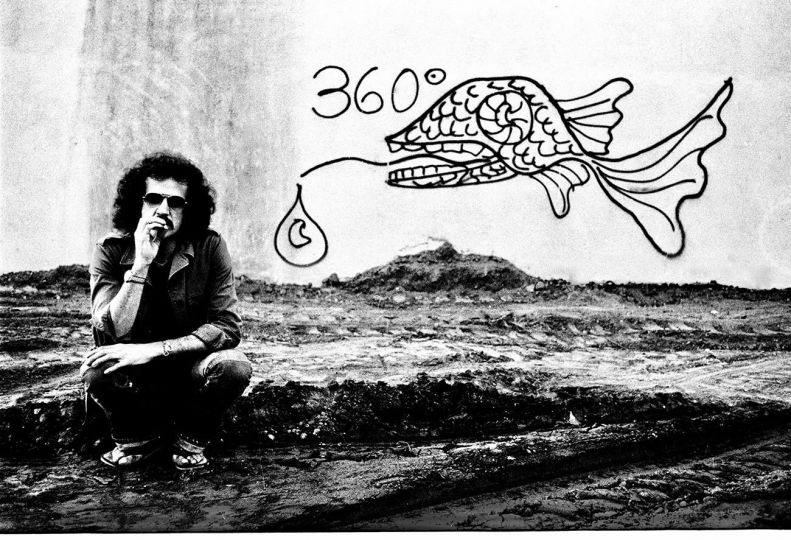

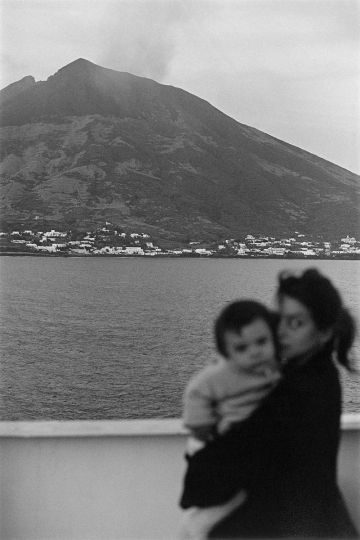

Women At Work does not open up a world beyond that of a group who share a workplace but in Kűnstler-portraits the canvas is a broader one. Paris moved to Prenzlauer Berg in 1966 when it was a working-class district of Berlin and it was there that she first found a focus for her interest in photography. Given that her subject matter was the proletariat, she was able to work without constraint from nosy authorities charged with the policing of cultural representations. Without wrapping herself up in the authorized tenets of socialist realism, she found a direction that was not in open conflict with officialdom: ‘I’ve always been drawn to the everyday, the unspectacular. But I didn’t photograph it clinically, aseptically; rather, I tried to reproduce it as realistically and as hauntingly as possible.’ Her marriage to an artist had opened a window into the bohemian aspect of GDR culture and she became particularly interested in film. The aesthetic influence of Italian neorealism, as well as photographers like August Sander, may be part of what she means by saying she sought to present reality ‘hauntingly’. Walter Benjamin, responding to Sander’s work, noted: ’Whether one is of the right or the left, one will have to get used to being seen in terms of one’s provenance’. In Kűnstler-portraits, Paris photographs Prenzlauer Berg’s provenance and one aspect of its social milieu emerges through a series of portraits of women and men who are committed to their art, uncorrupted by filthy lucre. Some of the figures’ gazes may seem too serious, the faces are those of communist nonconformists, but they party in a spirit of comradeship and Paris is able to bring her camera close to their faces because she is close to them in other ways as well.

Her photographs are infused with a sense of tristesse which cannot be explained away with platitudes about material austerity in the GDR and nor can it be attributed to ostalgie. The melancholy is softened with a tenderness that is accented by her decision to use black-and-white film (it wasn’t because colour film was too expensive in the GDR). With colour, she says, ‘the eye can get lost in the contrasts’ while with black-and-white ‘the composition seems clearer, so you can abstract more of what see’.

What Helga Paris could not see was the snake in the grass, the Stasi informer, the Judas who was accepted as part of Prenzlauer Berg’s free spirit. One of her photographs in Kűnstler-portraits is a group portrait taken in the studio of the sculptor and graphic artist Hans Scheib. Eugen Blum, in an informative essay at the end of the book, identifies a young man sitting to the far right by the table; a woman’s hand rests on his shoulder, innocently unaware of who he really was.

Sean Sheehan

Women At Work is published by Weiss Publications and Kűnstler-portraits is published by Spector Books.