At Paris Photo 2022, I turned a corner and was caught by a wall of small format prints in dark sepia tone, those were genuine gelatin silver prints. Looking closer I saw carcass of tanks and ruins from bombed buildings, I realized suddenly that the Ukraine war had come to Paris Photo! One image in particular attracted my attention: did this Jesus on the crucifix lose his arm after blocking or deflecting a rocket from striking a residential building behind? Was that worth sacrificing one of his arms? That’s an amazing quasi miraculous picture from the war photography series by Ukrainian photographer Vladyslav Krasnoschok, these are a sort of after the combat landscape photography, more “théâtre de barbarie”. There is abundance of video reporting on the Ukraine war but looking at a still photograph of Armageddon style of bombs and destruction is a different goosebumps experience. From my archives of Chinese photography, the first war photographer active in China was Felice Beato (1839-1909). Beato recorded the aftermath of the attack by the British naval forces on the Dagu forts near Tianjin, China, during the second Opium War (1860). The conditions on the battlefield, the bulk and heavy weight of the photographic equipment definitely did not allow taking snap shots of live action such as Robert Capa’s famous “Falling soldier” (September 1936) or “D-Day landing on Omaha Beach” (June 1944). therefore, Beato was reduced to exposing the scenes of destruction and dead bodies in his large format view camera, on a tripod and under a dark cloth, it was reported that he even instructed soldiers to arrange the dead bodies in order to fit within his frame.

From 1860 to 2022, there are 162 years that separate Beato’s Chinese War Theater from Vladyslav Krasnoschok’s Kharkiv or Donetsk killing fields. If we struggle between the esthetics of war photography and the barbaric atrocities, British greatest war photographer Don McCullen had this to say about “the voice to seduce people”, in a 2014 BBC interview: “We cannot, must not be allowed to forget the appalling things we are all capable of doing to our fellow human beings.” McCullen wants to convince us to keep looking, in spite of the unspeakable horror. “Often, they are atrocity pictures… But I want to create a voice for the people in those pictures, I want the voice to seduce people into actually hanging on a bit longer when they look at them, so they go away not with an intimidating memory but with a conscious obligation.”

I asked Vladyslav whether he considered himself a photo-journalist or an artist, whether he was “embedded” with the Ukrainian army, he answered: “I consider myself first and foremost as an artist documenting war. Imaginative, beautiful photography is important to me. Of course, I had to get accreditation from the Ukrainian armed forces. And it’s very difficult to shoot certain subjects, you always have to get additional permission. I see a lot of bodies and corpses. It’s unpleasant. But I look at it as an artist, as a viewer, I distance myself from it. It’s important for me to see the beauty in this horror, to convey the image of war.”

On the 6th of August 1943 during the Sicilian Campaign, after the US army had captured the town of Troina, Capa entered the devastated town with several mine detector squads, they found “a town of horror, alive with weeping, hysterical men, women and children who had stayed there through two terrible days of bombing and shelling, seeing their loved ones killed or wounded, their houses destroyed and whatever was left pillaged ruthlessly by departing Nazis”, those are quotes from Herbert Matthews’s book: “The education of a correspondent” (Praeger 1971). The scene resembles almost what we could imagine to be the state of destruction or carnage in Ukrainian towns unmercifully bombed and shelled by Russian forces. Whereas Capa experienced sand and dust in Italy, in Vladyslav Krasnoschok’s pictures it is a world of muds and waters and darkness. Dead bodies (men and animals) lying on the roadside, collapsed bridges over black waters, unexploded ordinance and rockets, one was planted before a church like a tombstone… amid the grimness of the war-scarred land, Associated Press described the psychological scars of war, soldiers suffering from meningitis, contusions, amputations, lung, and nerve inflammations, sleeping disorders, skin diseases, and cardiovascular illnesses, among others.” One of the fighters described sleeping for months in muddy, cold trenches. “We worked in conditions that were bad for our health. It’s bad, it’s damp, it’s wet, we have back pain, leg pain, we carry heavy equipment.” And snow and icy weather are coming.

From the New Yorker (June 2022): “anti-war photographer”, Jim Nachtwey in Ukraine sent this text before getting some sleep: “The barbarity and the senselessness of the Russian onslaught are hard to believe even as I witness them with my own eyes. Bombing and shelling civilian residences, firing tank rounds point-blank into homes and hospitals, murdering noncombatants in militarily occupied areas are all tactics being employed by the Russians in a war that was inflicted on a nonthreatening, neighboring sovereign state. . .. ‘Ordinary’ people are displaying extraordinary courage and determination, if not downright stubbornness, in the face of tremendous destruction and loss of life.” His refusal to avert his gaze from the true costs of conflict belongs to a larger mission: to keep the world from doing so.

After liberating Paris in August 1944 Capa thought wrongly that war was over, sitting at the bar of Hotel Scribe he wrote (in Slightly out of focus) “I was tolling the knell for the noble art of war photography, which had expired in the streets of Paris…There would never again be pictures of dough boys like those in the deserts of North Africa or the mountains of Italy, never again an invasion to surpass that of the Normandy beach, never a liberation to equal Paris.” He was wrong, and paid the price with his life by stepping on a land mine in Indochina (25/05/1954).

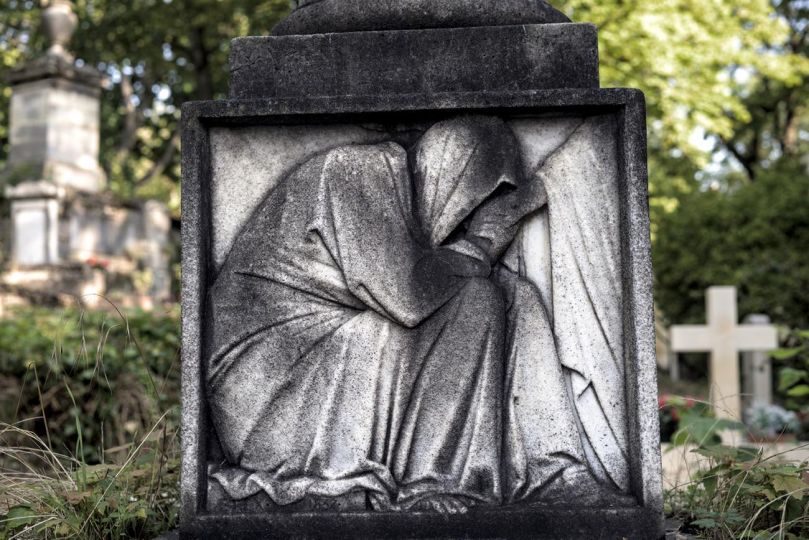

Let’s return to Vladyslav’s one-armed Jesus on his cross, this is a beautiful Orthodox cross, with three crossbeams, the top beam usually reserved for the inscription INRI (Jesus of Nazareth King of the Jews), the longest horizontal bar is where Jesus hands were nailed, and the lower one serves as footrest, it is slanted. Because Jesus was crucified along with two other thieves it is said that the footrest bar that points up to the thief on the right hand of Jesus meant that he was a “good” thief so he would go to paradise, on the other side, the bar pointing to the bottom means the “bad” thief will go to hell. War seems to be a never-ending business, but it has to end eventually like all wars, there is no need to ask Vladyslav Krasnoschok who is the bad guy that will go to hell.

Jean Loh

Vladyslav Krasnoschok is represented by Alexandra de Viveiros Galerie Nomade www.alexandradeviveiros.com

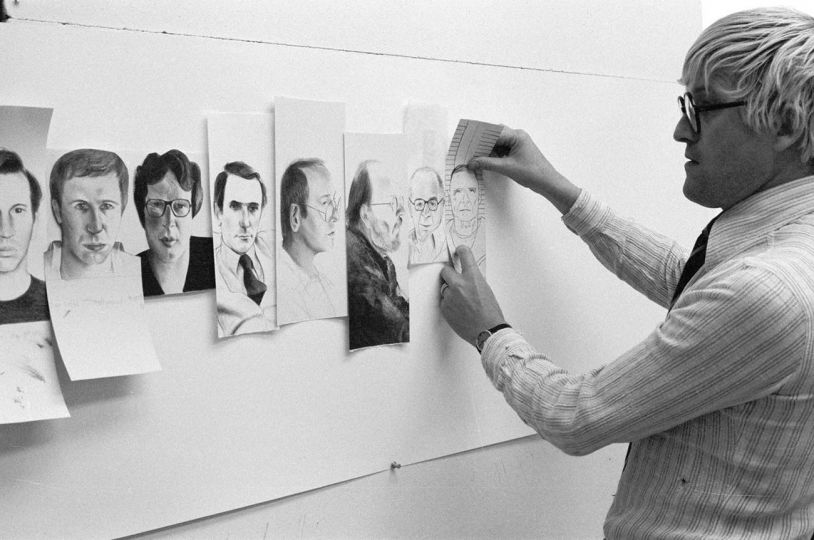

Vladyslav Krasnoshchok (born in 1980 in Kharkiv, Ukraine), has studied at the Department of Dentistry at Kharkiv Medical University (1997-2002). From 2004 to 2018 he worked at the Kharkiv state clinical hospital of emergency aid. Vladyslav has been actively practicing photography since 2008 and joined the Shilo Group since 2010 (together with Sergiy Lebedynskyy, Vadim Trykoz and Oleksiy Sobolev). Apart from documentary photography that he aesthetically transforms using different technical manipulations, he also uses photos from anonymous archives. He practices hand-coloring from methods that evolved in Kharkiv photography in the late 1970s. He also combines shots with sculptural objects, and experiments with graphic art, engraving and street art.