A visit to a home center store in Tokyo, where I live, is to fully immerse oneself in the spectrum of plastics – carbon-fiber this, Teflon that, shelves full of plastic artificial turf, plastic faux-wood floors, shiny-plastic rice cookers and coffee makers; plastic plants in plastic pots – shampoo, soap, skin lotions and make-up packaged in every color of the plastic rainbow.

Even 60% of our clothes are made from synthetic fibers – plastic. Aisle upon aisle of cheap, polyester, Lycra and acrylic clothing – spanning all age categories from cradle to grave – hanging in neat rows of racks.

Finally, consumers wait patiently in lines, pushing plastic shopping carts, preparing to pile their purchases onto a plastic conveyor belt, to be scanned by a clerk into a plastic-encased cash register, paid for with a plastic credit card, before stuffing it all into single-use plastic bags to be carried home.

Now after decades of overuse of single-use plastic, the planet is literally drowning in the plastic we’ve thrown away. By 2017, the world had produced a grand total of 8.3 billion metric tonnes of plastic, one tonne for every person on the planet. Most of it, 6.3 billion metric tonnes, can be found in landfill sites but another 8 million metric tonnes of plastic enters our oceans each year because roughly 2 billion people live within 48 km (30 miles) of the sea.

Plastic is literally in every corner of the planet. In 2019, researchers found microplastic in Arctic ice in greater concentrations than in the surrounding Arctic Ocean waters – the same year, explorers found plastic in the Marianas Trench in the Pacific, the deepest place on the planet. 46% of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch by mass is made up of plastic “ghost” fishing nets, lost by fishermen.

Zooplankton, minute organisms that form the very foundation of the marine food chain, are consuming microplastic, and microfibers from synthetic (plastic) clothing – mistaking them for food, because, unlike most other materials, it does not biodegrade. Plastic breaks into smaller and smaller pieces – of plastic. They eat less nutrient-rich food while absorbing toxins from the plastic. These toxins are passed up the food chain by predators. Those toxins accumulate, most affecting those at the top of that fish-consuming chain like sharks, toothed-whales, seals, seabirds and us. 90% of seabirds are eating plastic according to an Australian study in 2015. Some seabirds have been found with so much plastic in stuck in their stomachs that there was no room left for food. Slowly they starve.

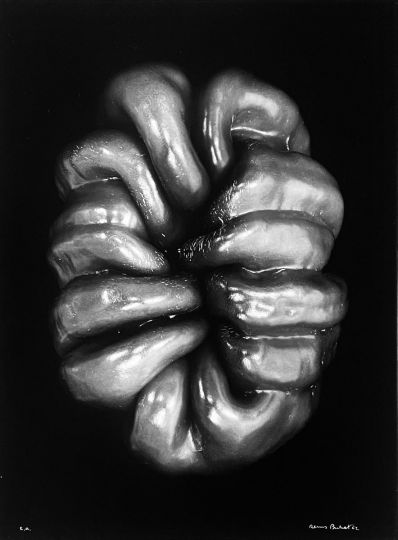

This series explores the environmental plague of plastic waste that bears down hardest on the developing world, but the challenge of plastic waste disposal spares no country.

James Whitlow Delano