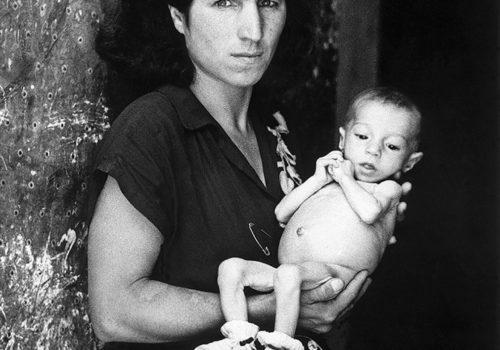

Evolution: Is it as ugly as we thought?

One view of photography’s digital age

“Where’s my film? Did Kenny [the courier] show up yet? Is it in the lab? I need this logged in now.”

It was 1993, at the height of the war in Bosnia, and mounds of film were piling up for all sections of the magazine, news and the arts alike. Wow! A hell of a first day at work for what I thought would be a two-week post on the photo traffic desk forNewsweek.

In that heyday of magazine journalism, with dozens of photographers on assignment on a weekly basis, few if any of us could see what was coming — the age of the Internet, email and, yes, the digital camera.