In the spring of 2022, two Parisian exhibitions dialogued, intensely, without those in charge (artist, curator, gallery owner, etc.) perhaps being aware of it.

These are Les Fantômes d’Orsay by Sophie Calle, at the Musée d’Orsay, and L’Esprit des lieux by Charles Matton, at the Dumonteil Contemporary gallery. Some time later, Sylvie Matton sent us this text. It’s great and we’re publishing it today.

JJN

A mesh of texts, objects and photographs, Les Fantômes d’Orsay looks like a treasure hunt in the footsteps of Sophie Calle, in Sophie Calle’s head. It is a mise en abyme of memories – hers in search of others –, the sharing of an adventure lived secretly, intimately, when she took up residence between 1978 and 81 in the Grand Hôtel Palais d’Orsay adjoining the Gare d’Orsay, an old palace then in disused for five years. Between living memory and free creation of the artist, the jubilant story unfolds: the small wooden door which opens on the Quai d’Orsay, the monumental staircase mentioned (but of which no photo testifies), the hours spent in empty spaces, choosing room 501, leaving before dark, returning the next day. It is an in-between, an illusion of time stopped, between the bygone luxury of the palace and its announced destruction: one day soon, the architects would draw up the plans for the future Musée d’Orsay, the workers would arrive, the deafening bulldozers would shake the walls and the frozen time, shattering the silence and, on the ground, the skeleton of the dilapidated hotel and its ultimate tinsel.

In the meantime, Sophie Calle had excavated the site like an archaeologist, appropriating its spirit by her mere presence. She photographed in black and white the maze of corridors and deserted rooms – spaces both familiar and unreal since their abandonment to time – some furniture and accessories that were now useless, even absurd, like this wall-mounted black bakelite telephone, silent for five years.

She collected vestiges of an accomplished past, “modest debris”, her trophies which she carried in a suitcase, without a specific objective, but thus preserved them from destruction and oblivion: rusty keys, locks, bells , enameled red metal plates, engraved with the number of the rooms and torn from the doors, files of the hotel’s customers – with, manuscript surname, first name, profession, date and price of the room – these few poignant traces evoking a a fleeting hotel episode in an existence long since erased; or the little words addressed to the mysterious and almost anonymous Oddo – the essential know-how, to whom the numerous written requests for plumbing repairs reveal the deterioration of the hotel before its final closure.

During the obscurantism of autumn 2020, when non-essential places closed, it was through another back door that Calle was invited to rediscover the Musée d’Orsay and to photograph paintings and sculptures emblematic of the art of the 19th century, that became spectral under the only light of a flashlight. The space, thus invested from one era to another, from one anthropological site to another, would welcome in 2022, exposed on the walls or on pedestals, these resuscitated ghosts, those of confinement and those collected forty years earlier, exhumed in Sophie Calle home from a trunk sarcophagus. Apart from objective chance, the poetic loop is complete.

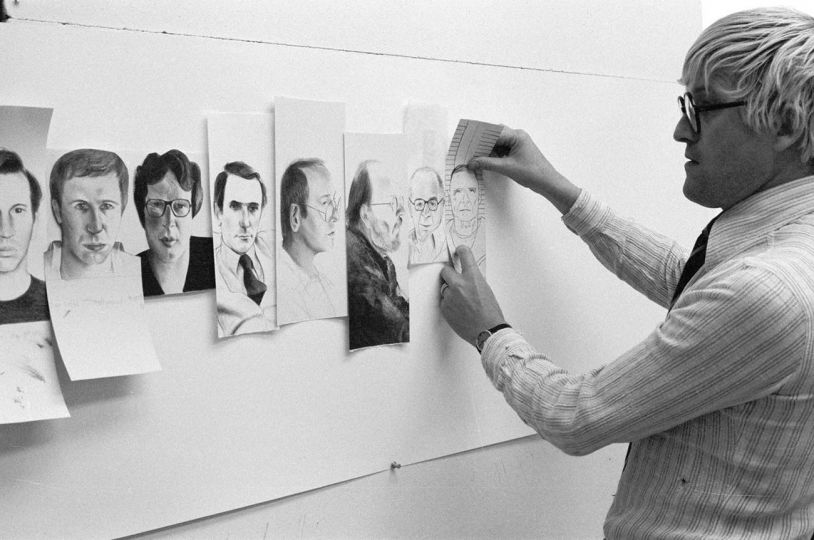

At the same time, in the beautiful space of the Dumonteil Contemporary gallery, the exhibition Charles Matton, L’Esprit des lieux confronts twelve “boxes” of “Interiors”, twelve spaces of an often intimate daily life, large format B/W photographs of interiors. These quickly turned out to be artistic simulacra: they are not the captures of real interiors, but those of “reductions of places”: Charles Matton sculpted each element of the model to the scale of a seventh, he modeled the sofa sculptures, painted the whole thing with perceptible touches of color – hot and cold confronting each other in vibrations on the walls, the sofas and the curtains. Then he lit up these “reconstructions of places” according to his wishes, with interchangeable lights: diffuse or in rays streaking walls and floors.

The first objective was pictorial: after the creation of the elements of this parallel universe, the artist would photograph his installations. Avoiding the laborious task of the horizontal and vertical lines inherent in classical architecture, he thus offered himself the pleasure of affixing, with great freedom, the pictorial style on the prints obtained. But it is ultimately the entire process that Matton started exhibiting in 1987 at the Palais de Tokyo, Paris. Because, parallel to this creation, he got caught up in the game of reducing places to three partitions and a window: his first boxes.

If, in L’Esprit des lieux, the photographic illusions, selected by Charles Matton before his death, offer summary living spaces but magnified in an approach linking aesthetics and ethics, they also tell the genesis of the boxes. The scale model being painted as it would have been painted on the canvas, the prints obtained are “photographic illusions” which oscillate from painting to photography. Confronted with the boxes, these large-format silver prints are visual decoys that disturb the eye, playing with proportions, appearances and reality.

For any visitor to the two exhibitions, a first analogy is obvious: the architecture of the Grand Hôtel Palais d’Orsay and many reconstructions of places by Charles Matton are Haussmannian, resulting from the renovation of Paris by Baron Haussmann, prefect of the Seine, in the second half of the 19th century. Proceeding from the invention of the private space, these vast apartments with long corridors leading to numerous rooms represent “the hegemony of the bourgeois model and happy respectability” as Séverine Jouve so aptly describes them (1). This is the time when, under the spirit of literary decadence, the home asserts itself as a microcosm, a metaphor for moods. It is a “model-apartment”, a “meditated dwelling” that Baudelaire dreams of building for himself, an ideal “dream”. The aesthetes who advocate a heady decoration, a flashy taste for the profusion of objects and knick-knacks, then oppose those who, like Maupassant, find that “all this is dreadful, pretentious, vain, shameful”.

Haussmann’s action having repercussions far beyond Paris, in many European capitals but also in smaller cities, the Haussmannian interior was experienced differently, becoming more democratic in a way from the second half of the 20th century. While the oak floors and long corridors remain, the rooms are smaller, the ceilings lower. The plinths, the door frames, the geometric ornaments of the walls are the emblematic sign of an urban elegance that is more discreet. Over the decades, the luxury originally induced in a Haussmannian interior is neutralized.

Thus, Sophie Calle’s images of a deserted late 19th century hotel doomed to imminent collapse, like those of Charles Matton’s illusory interiors, are all representations of stripped-down urban “dreams”, settings for imaginary stories. No window opens to the outside. Ignored from the bowels of the building, the city is absent, except for the sunlight that it diffused through often invisible openings. Loneliness is not embodied, as in Hopper’s paintings, in a relationship of reciprocal voyeurs between the closed world of the inside and that of the outside. Calle broke into the premises before taking them over. With a look that wants to be as objective as possible, Matton has recreated living spaces that remember those who have deserted them, like so many proposals for feelings. It offers the vision of a world when no one is there to see it, supposedly peaceful.

We don’t know much about what Sophie Calle really lived for so many days, over several years, in this hotel maze. She claims (in the exhibition as in the beautiful book (2) that accompanies it) that, projected “into the world of Bob Wilson”, “in order to imitate his dervish dancers”, she trained ” spinning around in the ballroom every day”. She adds: “I don’t remember what I did during my days. I was there, waiting for something. »

According to him, she would have spent hours between the rust-spotted mirrors of the ballroom, spinning around, sort of spinning around in circles; or, sitting on a tired seat, waiting for who knows what. How to believe it? Her memories of such an initiatory adventure, perhaps nourished by improvised rituals, would therefore escape her forty years later – unless she was afraid, by resurrecting and sharing them, of profaning her palace of time a second time?

Like a character in a novel by Virginia Woolf – the writer of time, empty houses and embodiment in all things – she continued the quivering of a breath of air in the maze of empty rooms that keep life in memory? On the threshold of the doors, did she hesitate to take the step? Did she hear the juxtaposed voices of hotel passengers, customers or staff members, proposals that would haunt this building until its fall and final disintegration: “But we have other lives, I believe , I hope. We live in others, Sir… We live in things” (3).

Listening to her curiosity, to the joy of the forbidden, of sacrilege braved, in this voluntary, temporary and constantly renewed confinement, has she experienced a new response every day to the expectation of her senses? Did she know there the dizzying feeling of emptiness, of patience, of being overwhelmed, of the sickness of fear, did she speak to the walls, to the creaking woodwork? Did she whisper, shout, cry on the walls, did she sing, try to echo, advanced on tiptoe not to have the floors creak? How many lives has she told herself? Did she hear the rats running in the attic, the cockroaches behind the walls, did she draw up lists of all kinds, amusing and absurd inventories but ultimately not that much. Has she lost herself, reincarnated into others – ghostly doubles of herself?

Did she wander between the visible and the invisible, feel the dilapidation of the place as a metaphor for a mental or physiological state? In this essential and shifting reality of relentless deterioration, did she believe that frozen time abolished duration? Between the past splendor and the announced apocalypse, in this dead time, in this empty passage, did Calle accept or deny, privileged spectator, the passage of time?

Yet she knows the reality of it and has captured it, she has photographed the corpse of a cat in putrefaction and exposes two stages of its decomposition: only time persists in dissolving the molecules in this way. So there was also the smell. Two shots without caption: in which room did the cat die, of what and when did it die? Sophie Calle does not act on the fatality of the place, she only moves the relics, her fetishes brought home in a suitcase (what size, what color is the suitcase brought empty, in how many trips?). A fugitive somnambulist, she looks through the lens of her camera at the remains of the cat on which the place feeds, which the degraded palace is gradually swallowing up.

In this multiple space which contains both its glorious past and its decline, where the paint is peeling, the plaster is crumbling, the metals are rusting, the acuteness of the artist’s gaze focuses on the familiar details that, out of habit, we have forgotten how to see: switches, sockets, baseboards, pipes, details of the plumbing torn from the walls. Challenging appearances to the point of recreating the reality they camouflage, Charles Matton also photographed these “details”, he also sculpted switch reductions, he twisted metal rods, made pipes of them. . In photographs, “photostats”, drawings or elements integrating a box, sanitary facilities have, as for Sophie Calle, solicited her attention and her creation as much as a living room.

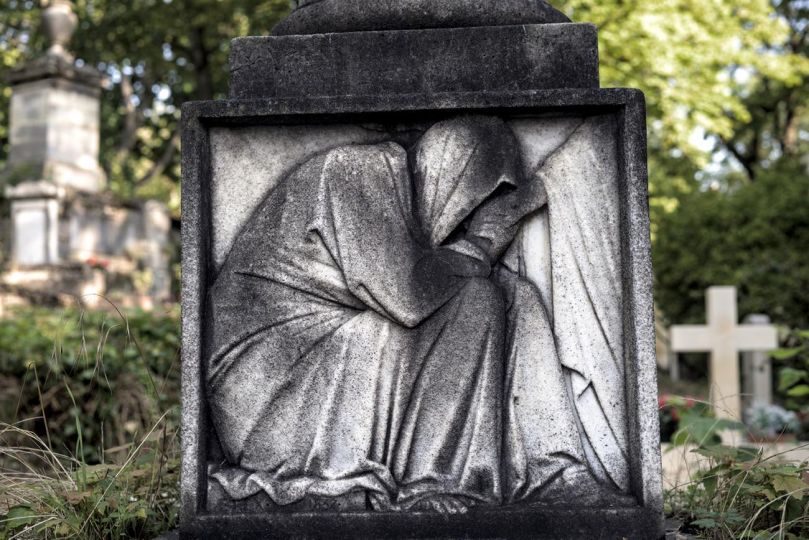

Matton is also sensitive to the ghosts that haunt places where people live. In his highly autobiographical feature film of 1994, La Lumière des étoiles mortes, the child who plays the author-director at the age of ten (his own son Léonard) says to a young adult, following the drawing with his finger which oozes on the wall: “You see, that, mom says it’s the ghost of the washbasin.” The traces present on the walls are those of absence. The ghosts of toilets removed, pipes ripped out or a picture taken down – are the traces of time.

Many analogies reverberate from one work to another, including boxes which, through different sets of mirrors, lead the visitor’s gaze into mise en abyme reminiscent of the endless corridors of the deserted hotel. Any hallway, whether it is made of walls and doors, walls of books or bottles, invites us to take a quick forward mental journey. We can regret that Charles Matton did not reconstruct a Haussmannian hotel corridor; perhaps he would have added an evocation of humans in this infinite perspective, on the aligned repetition of the same shadows and contrasting lights, by a deliciously outdated detail: a row of male shoes placed in front of the door of the rooms, those that the customers recovered, polished, in the early morning.

But the two works also confront each other in a shift that seems to be necessary, from black and white for Calle to color for Matton, from shadow to light, from the fatality of annihilation to a serene hope. The reverse in a way of the proposition of La Chambre double by Baudelaire, when the lived space annihilates the dreamed space. A knock at the door by an intruder will have sufficed to destroy the harmony of thought, for the paradisiacal room described by the poet to be transformed into a hovel, the perfume into a fetid odor and, with the resurgence of time, reverie. of the spiritual chamber in anguish of the damned. It is the opposite inspired by the discovery of Charles Matton’s color photographs following that of Sophie Calle’s images.

Perhaps the reason is that Matton’s visual creations always fight an essential doubt, a central question in his artistic quest for the real: what about the existence of things in the absence of an observer? More clearly: “Would there be trees if we didn’t see them?” (4)? The reality camouflaged by appearances will be confirmed if the observer manages to abstract himself from it, to objectify himself, in particular by dissolving himself in the mirrors. It is tempting to find there too, in these creations of silent interiors, a similarity with a thought of Woolf expressed by a character in La Traversée des apparences : “I want to write a novel about silence; what people don’t say. But it is very difficult. The silence induces luminous visuals.

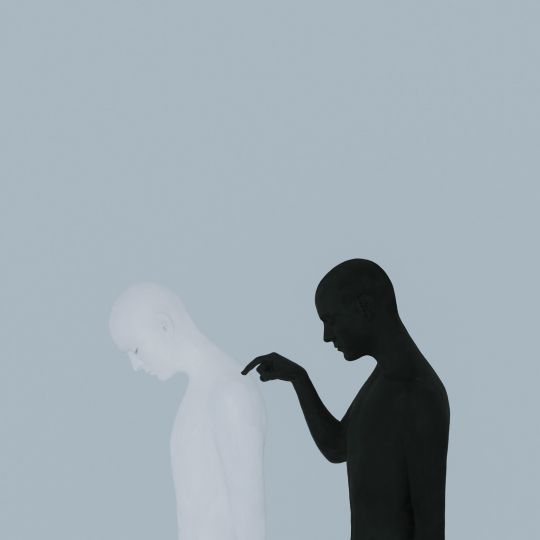

Subject or object? It is this primary questioning that defines the orientation of a work.

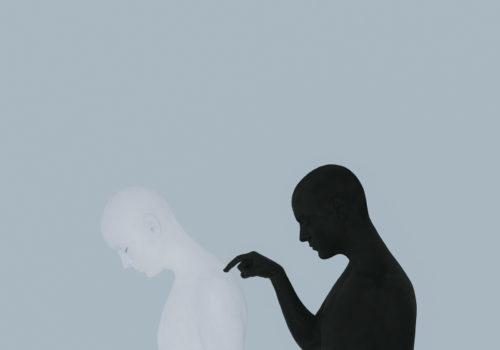

On the one hand, a living body integrates a space, fills it with its presence and accompanies its degeneration by escaping contamination; on the other, a gaze, as objective as possible, admits the reality of interior spaces – metaphors for those of the mind – before recreating them on another scale, in order to safeguard their integrity, finally tangible.

On one side, a 250-room hotel doomed to imminent annihilation, on the other, creations that play with time, without the slightest sign of degradation. Only the human absence, this hollow presence confirmed by the traces left on the wall by the paintings recently taken down, gives these illusory spaces a perception of strangeness – a diffuse apprehension in the face of the indelible mark of the absent, of the danger they may have incurred, to their demise. Has a couple separated between these walls, torn perhaps? Did the humans who lived there move away? Will they come back or never, will others join the place soon? The dramaturgy can only be imaginary in the fiction of these ecstatic spaces.

The confrontation of these two creations, dissonant testimonies of reality, will perhaps find a resolution in the few words of Mallarmé at the very end of his poem A throw of the dice will never abolish chance: “Nothing will have taken place Except the space Maybe A constellation” (art maybe?).

Nothing will have happened except the space!

Between the decay of a condemned space and the framing of a luminous section of life, both interchangeable in another space-time, there is only a moment, a fragment of time, a hint of eternity.

In art, where everything is possible, it is also true in reverse.

Sylvie Matton

(1) in Obsessions et perversions dans la littérature et les demeures à la fin du dix-neuvième siècle, Editions Hermann

(2) L’Ascenseur occupe la 501, Sophie Calle and Jean-Paul Demoule, Editions Actes Sud

(3) ) Entre les actes, Virginia Woolf

(4) Questioning Maggie in Les Années, Virginia Woolf