Archives – October 2012

Simon Crocker was Managing Director and, subsequently Chairman of The Kobal Collection, until he sold his shareholding in 1999. He has been Chairman of the John Kobal Foundation since 1991. He worked closely with John Kobal in establishing the Collection as the leading independent film photography archive worldwide.

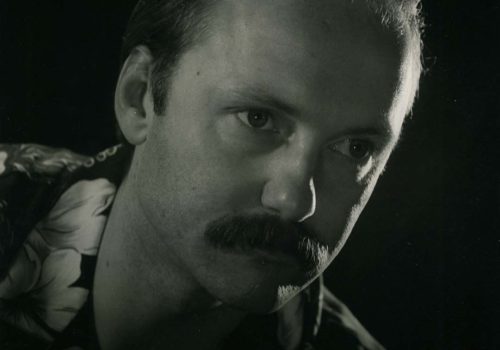

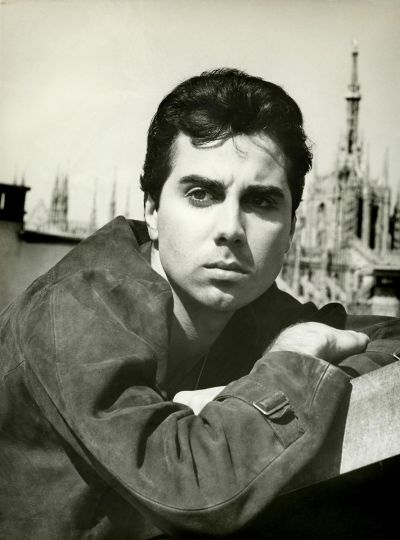

It was the voice that first caught my attention. It was 1964, at my parents house in London. I was sixteen, John in his early twenties. His voice preceded him, coming at you like an advance guard proclaiming his imminent arrival. A deep, booming voice firing out machine gun speed sentences that never seemed to end as they swirled around you. When he turned the corner, you found yourself looking up at a dark haired, moustachioed, six foot five inch (1.98m), well built young man towering over everyone else. As a teenager, I didn’t always understand what he was saying, and he was saying so much all the time, but you liked the way he said it with a quizzical smile and compelling energy.

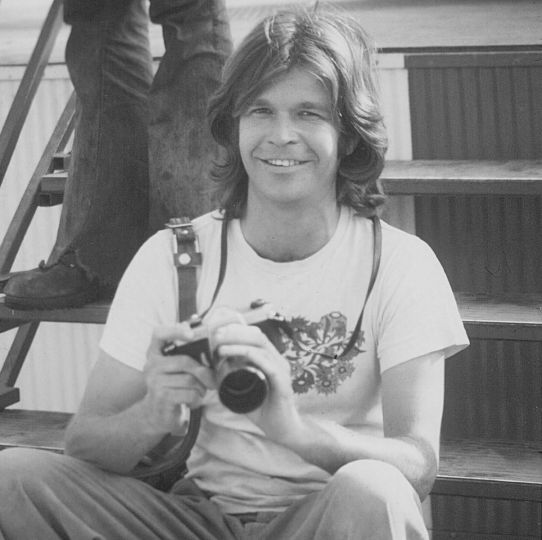

Although John was in and out of our house fairly regularly, I only really got to know him about five years later. He was friends with my two older brothers and my parents. My mother used to babysit Sam, his beautiful Weimaraner dog, whenever he went away on his frequent journalistic forays abroad. He was busy interviewing film stars for the Sunday Times Magazine, Harpers Bazaar, Vogue and many other publications which took him to film festivals and press junkets all over the world. As he went, he continually trawled for film photographs and promotional materials – portraits, scene stills, off sets, posters, lobby cards etc – to add to his burgeoning collection which he then used to illustrate his interviews.

I left university with a law degree in 1970 and then travelled around the USA on a Greyhound Bus for six months having a grand adventure. On my return to the UK, I had decided that the law was not for me and that I wanted to get involved in the film and music industries. As a stopgap, John, who was still travelling on assignments, asked if I could sit in his flat in London and answer any phone calls. Publications and television companies were beginning to discover the existence of his photo collection – now some twenty filing cabinets – and calling to see if they could perhaps borrow some. John – keen to widen his journalistic contacts – was happy to help them. When, later, cheques for this usage started to drop on his doormat, John realised that this might be a way to help subsidise him so he could do less travelling and concentrate on writing his books about cinema.

As he never intended it to be a business, at the outset he never organised his collection as one. Yes, stars had their own files, as did films, and were in alphabetical order but beyond that there was no cross referencing or categorising and it was difficult for anyone, except him, to find anything more complex or rise to the challenge of fulfilling a request such as finding a photo of a man wearing a dinner jacket on a camel smoking a cigarette. I started to help build up his card index system so that anyone could use it (those pre-computer days had a beauty to them with the need for mental dexterity and dogged manual work!). This was a slow job that required patience especially as John often, on a whim, suddenly moved batches of stills from one file to another without marking it on the card system!

I had started going to movies regularly myself in my early teens (and even before that remember going to the National Film Theatre with my brother Chris to see things like Cantinflas movies. If you wanted to know about classic Mexican comedies then, aged 12, I was your man!). So working with John’s collection was a treat. I was able to lose myself in my favourite film stars portrait and film files but also discovered people and films that I had never heard of and was enticed into searching out.

But my immediate calling was elsewhere and in 1971 I left to go into the music business as a manager of a young girl singer who was stirring some interest and eventually a couple of other artistes too. But by 1976, although the music business had been a lot of fun and had hardened up my previously non-existent business sense, I felt it was time to move on. I was already working from the offices of my brother, Julian Seddon’s company who represented some of the top commercial photographers at the time – Art Kane, Lester Bookbinder, Francis Giacobetti, Derek Coutts and Mike Berkofsky. When he was away I started to cover for him and then started to put together shoot budgets, find locations and help produce shoots.

My brother was also helping John with the calls he was starting to get from advertising agencies and design companies wanting to use the graphic imagery of old film stills and he did not know how to handle it. So my brother, and then gradually myself, took on the task of negotiating fees, help sort out clearances etc. At the same time, the volume of calls requesting stills for editorial usage had also increased rapidly. John now had a secretary helping him but even this was not enough. One day, John sat me down and said he thought there was a real nostalgia for old movies that had caused a boom that might have five good years in it, maybe a few more if we were lucky. Did I fancy taking over the running of his business fulltime whilst I thought about what I really wanted to do? My first child was due and I liked the idea of something potentially more stable that might produce regular income. So I jumped ship and joined John for a fifteen year journey that continued up to his untimely early death in 1991.

Over those years, The Kobal Collection grew from the two of us and a secretary in London to, at the time of his death, about thirty people employed between London and New York (where we successfully set up an office in 1979). His collection had grown to nearly a million 10×8 stills and colour transparencies and had become an international by-word for film imagery working with virtually every major publication, publishing company and creative end user in the business.

Until the mid 1980s, John’s collection was situated at his cavernous third floor 1930s mansion flat in Drayton Gardens just off London’s Fulham Road and opposite the famous Paris Pullman Cinema, an art house venue that was sadly demolished in 1983. His flat was constructed as a very long corridor with a number of decent sized rooms leading off of it. The front rooms of the flat nearest its entrance housed the filing cabinets and were the centre of all activity. As they increased in number and were packed to capacity, we constantly lived in fear that the floor would give way one day and the ground floor occupant would inadvertently end up housing the collection.

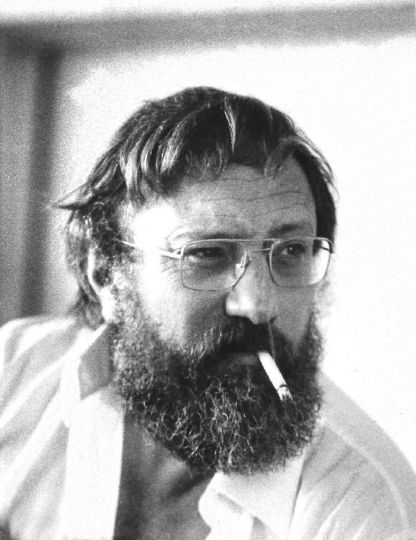

John was not what would nowadays be called “client facing”. Researchers and writers were a necessary evil he knew he had to tolerate but never quite mastered the art of it. As a researcher was quietly going about their business, selecting the images they wanted to use, John could sweep into the room dressed, as likely as not, in an embroided white kaftan and in his booming voice ask what they were looking for.

On being told, he’d scoop up their selection, cast his eye over it, give them one or two back and then furiously delve into the files to replace the ones he had confiscated from them. The new selection would be handed to the, by now slightly intimidated, researcher as being much better for what they wanted. They were accepted as a fait accompli and the client sent on their way! It was a nerve wracking experience for many but nearly all acknowledged later that John was right and had helped open their eyes to a wider range of possibilities than they had been aware of.

John was also a very generous spirit. If a friend was ever in financial difficulties, John would not hesitate to loan them funds knowing the expectations of repayment were very low. And he loved giving parties and his parties were often and famous. His steaming stews and goulashes were doled out to an eclectic group of guests from fashion designers to artists to journalists and screenwriters, actors (often including a handful of Stars from the Hollywood Golden era like Luise Rainer or Ava Gardner), directors and cinematographers. Conversation was witty and enthralling and a side entertainment was seeing some of the guests quietly slipping down the hall to the filing cabinets to examine what was in the files on them. If they were not satisfied with what they found, a few days later a bundle of photos would arrive to enhance their file!

For anyone who ever met John, he would be on the top ten list of the most memorable people they’d ever met. He holds the top spot in my list. He was an extraordinary person. Driven, exhausting, exasperating, aggravating but never dull, always intellectually questioning, very funny and tremendous company. It was not unusual to get a phone call well past midnight from John unable to contain his enthusiasm or damnation of a film, play or exhibition he’d just seen or book he’d just finished. Forty five minutes or so later he’d realise what time it was and end the call profusely apologising for waking you up. But by that time, you were wide awake and invigorated by his monologue and determined to either see or avoid the film, play etc in question as soon as possible.

He had high standards in everything he produced. He was never going to allow a book by him to be published until it was as great as it possibly could be. Publishers often trembled at his relentless phone calls ensuring the best end product. And no exhibition he curated could have less than a WoW Factor!

He could be particularly unrelenting when he was writing one of his books, trying to get constant feedback on his progress. He would often be waiting to start reading the latest chapter he had been toiling over to whomever came in the door first. I remember on more than one occasion being inside a toilet whilst John, oblivious to what you might be doing, stood outside continuing to read his manuscript to you through the door and pressing you for your thoughts.

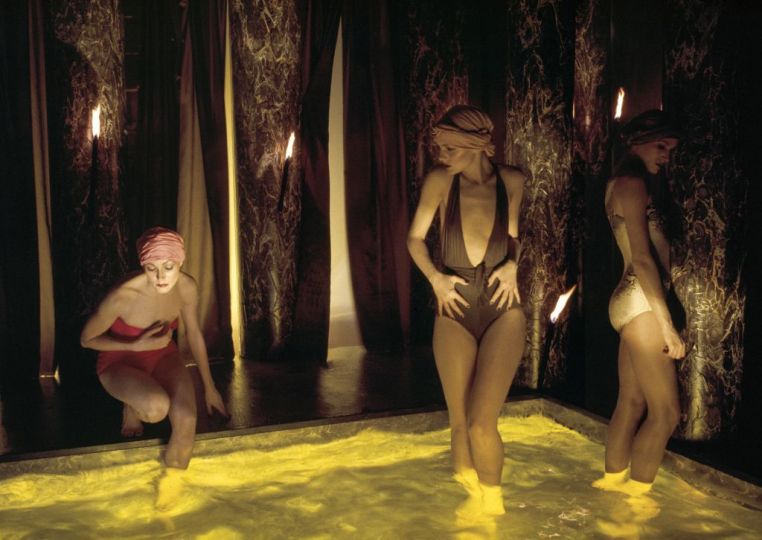

Before his death, in 1991, John wanted to leave some legacy that would help new, young photographic talent so he oversaw the setting up of The John Kobal Foundation as a charity to help promote portrait photography. He endowed it with his personal collection of original 10×8 negatives and vintage and modern signed prints of the work of the greatest photographers working in Hollywood during the 1920s to the late 1950s – the Golden Age of Hollywood.

After his death, I stayed on as Chairman of the Kobal Collection but it was never quite the same for me again and I sold out my shares in 2000 and moved on again, first representing photographers and then, with one of them, went into film development and production. My first feature film as a producer, uwantme2killhim, will be released in the UK in early April 2013 and other territories thereafter.

But I continue to remain as Chairman of the John Kobal Foundation, a totally separate entity from the The Kobal Collection since 2000. Through the foundation, we have kept John’s spirit and name alive through awards to emerging young photographers and by helping the commissions of new work by them as well as exhibitions and books culled from the foundation’s Hollywood archive.

John, more than anyone, encouraged my interest in getting involved in actually making movies and believed in me before anyone else ever did. He died just weeks before I finished my first production– a BBC television film called ‘Losing Track’ starring Alan Bates – but felt his approving presence around me at its first screening. He was starting to write scripts himself – and they were pretty good – as well as a musical intended for Bette Midler and if he had lived then he would have undoubtedly established himself not just as a man who was passionate about films but also one who was passionate about making them too.

Simon Crocker