Lives and works in Veracruz, Mexico.

My work is related to love, art and the violence. I am from a tropical country, colorful as a rainbow and so the colors and texture are so present in my images. I was born in 1975 in an industrial neighborhood in a small town in Brazil. Since the year 2002, I develop my research on violence and prisons. The project INSERÇÃO (Insertion), a photographic essay that registers the Brazilian prisons of the APAC (Association of Assistance and Protection of the Damned) method. A prisons model that is self-managed, in APAC there is no police presence. I hope to publish a book with the results of this search.

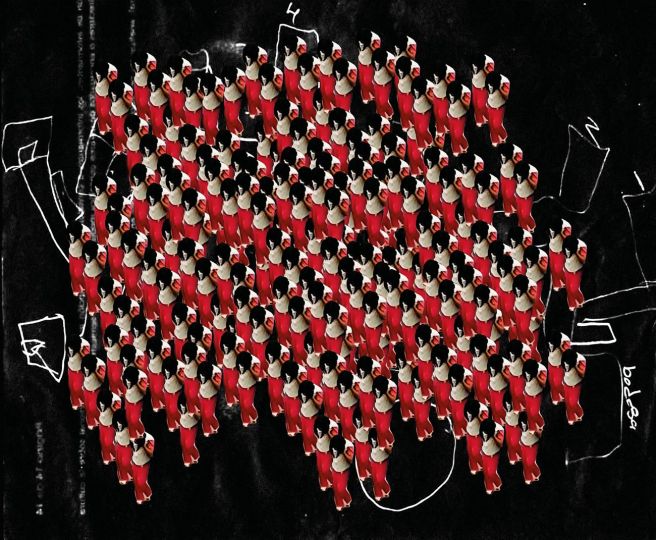

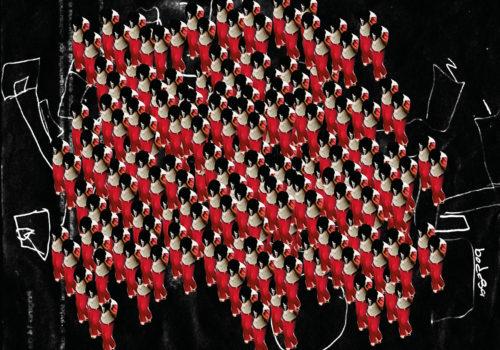

INSERTION | INSERÇÃO

The brutal life conditions inside Brazilian prisons, where tens of men cohabit few square meters’ cells under very bad health and hygiene service as well as, the random procedure of convicts’ placement managed by security authorities reveal the State’s inability to guarantee imprisonment in a nearly fair model. Public security is on a daily debate in Brazil, a country that counts on one of the largest prisoner contingents in the world. In addition, regular insurgences disclosed by prisoners against security inside the prisons, due to recently organizations attacks (PCC) in São Paulo, intensify the scenery of violence and end to make public a hidden reality. Just like the many other reasons which take thousands of men and women to prison, structural social problems, such as exposure to violence, lack of access to basic conditions of education, health and work, the prisoners’ stigma complete the panorama of marginalization: prejudice against former prisoners frequently takes to recidivism to crime leading to a vicious circle and hopelessness regarding social reinsertion. The most part of first time convicts in Brazil returns to prison at least once in life.

How can one discuss the issue considering beyond the social security context also the particular concerns of the subjects involved? How can one register voices and gestures, silences and gaze? After all, what lives, what bodies, what dreams and thoughts are weaved there, where our eyes can’t reach? It was necessary to go through the invisible wall dividing some men to others?

Frequent visits had to happened before I realized that those images were a personal attempt to prove that some wishes and dreams are common to every man and to be more aware of how important freedom is in human life.

The APAC method was designed and implemented by the lawyer Paulo Mário OTTOBONI in 1972 in the city of São José dos Campos (SP). The method includes 12 key elements of work, created after research and reflection to produce the desired effects. Since 1986, Apac is affiliated to the Prison Fellowship International, the UN advisory body for prison’s matters. In 1991, it was published in the U.S. a report stating that the Apac method could be applied anywhere in the world.

There are now over 100 units spread throughout the national territory, and in several countries such as: Argentina, Armenia, Bolivia, Bulgaria, Chile, Singapore, Costa Rica, Ecuador, El Salvador, Slovakia, United States, England, Wales, Latvia, Mexico, Moldova, New Zealand and Norway.

The sentence “any man can be guilty” coming out in the speech of one of the first convicts, I had the opportunity to talk was the door that opened a new perspective of the dehumanized world of the jail to him. Through the project Novos Rumos na Execução Penal (New Directions on Penal Execution) I was asked to carry out a photographic essay to document the Apac (Association of

Protection and Assistance for Convict) system. The Apac is a special prison model in which the convicts themselves are charged of the security and all other community duties inside the prison.

My experience inside the Apac since 2002, amongst visits and chats with convicts, resulted in a long visual project. An imaginary documentary, recorded through photos, videos, objects, letters, texts and sculptures, documenting a prison that privileges conviviality and social re-insertion but it is also a portrait of the everyday life of some men marked by a rough past of marginality and stories of violence. Ideas around crime and punishment inhabited Albert and he watched and was watched at the same time, being me the criminal as well as the eye keeper.

Rodrigo Albert