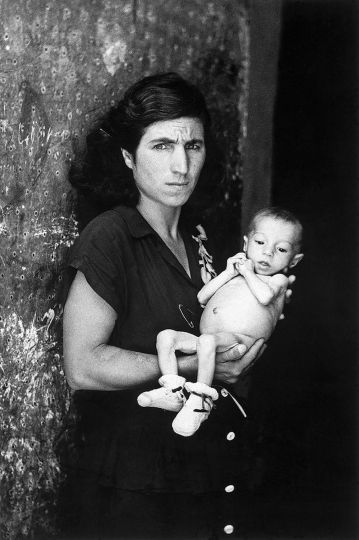

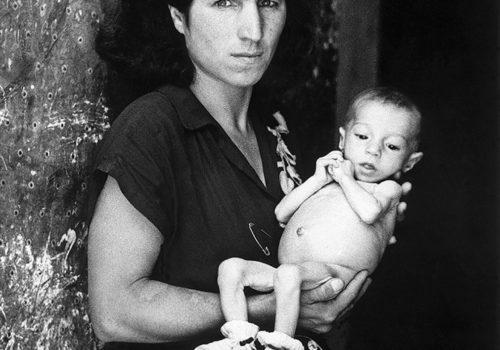

It was in the street, in the famous “school of hard knocks,” that this most popular of French photographers learned his poetry; his tenderness and humor and the compassionate gaze that he lavished on the world around him. His work was long thought to epitomize the Parisian picturesque – the unexpected anecdote and the lovable humor – but a more accurate analysis of his six decades of “fishing for imagees” reveals a depth and thoughtfulness that undoubtedly modify and enrich the immediate impact of his oeuvre. Robert Doisneau had a supreme sense of those absurd, unexpected situations that transform the meaning of a scene by delicate allusions

We cannot help but observe that the scenes created by Doisneau, like those of the comic writers, are more 5erious than they seem. “There is a kind of pathos about the bride drinking at the bar or the one on the seesaw at Gegene’s,” ‘ he noted, adding: “Humor is a feeling of shame for overt emotion. When the scene is too tender – or too cruel – you take refuge in humor to avoid that sense of embarrassment.”

Jacques Tati, Charlie Chaplin, and Raymond Devos number among the world’s great comedians. With them, laughter is a surefire reaction, but their drollery conceals a sadness, a bitter-sweet melancholy that leaves one’s smile a little strained. Robert Doisneau belongs in that company A number of his images, though very funny sing a melancholy tune all of their own and reflect a harsh and perhaps unconsciously discordant vision of the world and of humankind. This quality brings him close to Jacques Prevert and Blaise Cendrars, advanturers of the same ilk, striving to illuminate the cold and cheerless world around them with their rage and compassion. Throughout his long career, Doisneau always excelled both at capturing reality and at softening its edges with a dose of cauterizing humor.

His images have not aged – or at least, if they have, a great deal less than those of photographers considered more modern in their own time but which now seem thoroughly outmoded. No such thing with Doisneau authenticity imbues his every shot. Each is a veritable self-portrait, instantly evocative of the man himself, his warmth. finesse and bashfulness, his respect for others and, above all, his fraternity. That sincerity always disposed of any trace of pessimism while his instinctive sensitivity allowed him to transform any banality in the situations that his eye tirelessly discovered.

“So few have photographed my little universe that it has come to seem as exotic as a nature reserve with its own astounding brand of wildlife. I certainly don’t find anything to laugh at in these people … even though I myself have a strong desire to keep myself entertained and have never stopped having fun; I have created my own little theater.”

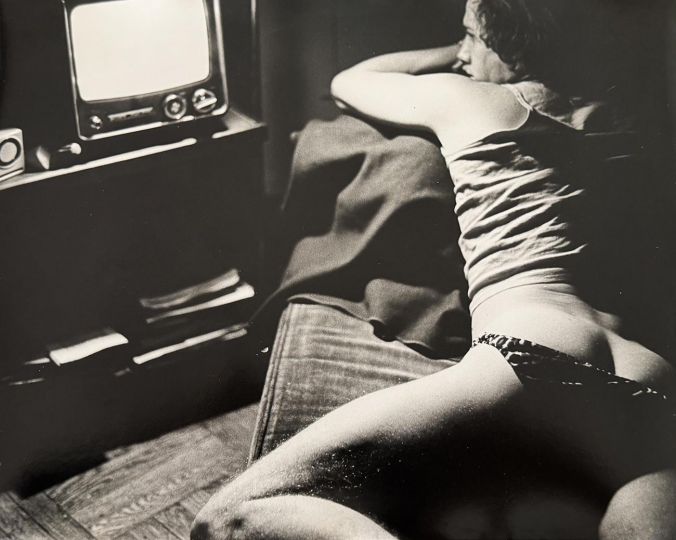

And Doisneau never stopped writing for this theater. Each image, explains Albert Plecy; “is the start of a short story or a short story in itself. Around the slice of life that it sets before you, you can reconstitute an entire quarter, a town, a festivity; an entire life, an entire epoch … ”

Doisneau confirms this: “To see is sometimes to improvise a little theater and wait for the actors. Who am I waiting for? I don’t know. I wait nonetheless.” As he puts it, “Paris is a theater where you pay for your seat in wasted time.”

And this has been the focus of his entire life. More a fisherman than a hunter, Doisneau has continued to harvest from the urban macadam a humanitarian bouquet of instants, encounters, and backdrops. Whence his interest in “values not listed on the stock market, elements hitherto considered negligible, which the caprices of light bring forth out of the shadows, revealing a new order and displaying their very own beauty and emotional power.”

Solitary to the last, Doisneau tirelessly patrolled his own carefully staked-out domain between Paris.

Gentilly; and Montrouge, the areas where he had always lived, though he had on occasion ventured beyond its perimeter. There, on his favored terrain, he excelled in picking those “little dried flowers” that now constitute a “herbarium” of some 450,000 negatives. Amid the great iconic pictures are a number of pearls, whose discovery give one the measure of a talent that has never ceased to seduce and dazzle us by its ability to lure into the lens the thousand and one aspect of daily life that are transformed into exceptional instants by Doisneau’s magic, sincerity; and tenderness.

Optimism is what characterizes his warm, committed, lyrical photography; sensitive to human suffering, that emerged in the wake of World War II. Known as humanist photography, its distinctive qualities are generosity; optimism, appreciation of the simple joys of life, and an invincible attraction to both the theater of the street and the symbolism of scenes that often reflect an admirable social cohesion. It was never a school of photography it focuses above all on the glances and smiles of people randomly eucountered. It reached its apogee in the 1950s and its favorite backdrop was the old streets and shiny cobblestones of his beloved Paris and its suburbs.

This was where Doisneau was born, where his emotional life was rooted and where he began to construct his little theater. He knew every centimeter of this territory.

“For me, walking from Montrouge to Porte Clignancourt is like filling in the dots: I can’t go more than 400 meters without meeting someone I know – the manager of a restaurant, a cabinet -maker, a printer, a painter or just someone in the street… I don’t like crowds, they frighten me. No, I’m looking for the individual, someone who holds your gaze, someone to talk to from the heart.”

From these encounters, some ambushes in situ some meticulously staged, arise veritable genre scenes; in the world of Jean-François Chevrier, they lie “somewhere between the formal portrait and the instant, they require both the capturing of the protagonists in action (it must be a familiar action) and their participation in the making of the image.”

By lending themselves -volontarily or not- to the photographer’s action, each protagonist guaranteed the authenticity of the photograph. This is no doubt why there is. in all these images, a human warmth, an almost familial atmosphere. that makes the spectator, too, an accomplice in capturing the instant. We allow ourselves to be caught in the delightful lures of this visual poacher, following him from the old walls of Paris to its bistrots. seeing through his lens the jaunty down-and-out and the dancer on Fourteenth of July, accompanying him from Gegene’s bar to the Tuilerie Gardens. Each of these places is inhabited by children, lovers. and other, astonishing personages.

Doisneau excels in recounting the thousand and one miracle of the street because his own roots are in the grim soil of the suburb where he was born on April 14, 1912: Gentilly. His father, Gaston was a plumbing surveyor who lost his wife in 1919 and remarried three years later. Hence, Doisneau’s rather disturbed childhood, compouded by a turbulent and undisciplined character. His eye was already on the street: “I loved the sheer delinquency of my friends from the slums: I had a high old time with them. There were Italians, Ukrainians. Pole and the local blokes, from Gentilly.”

By way of landscape. he had only the little industrial workshops on the banks of the Bievre. This filthy river – it runs underground today – was polluted by” the effluent of the tannerie and chamois-leather factories but remained in his eyes an outpost of nature in a chaotic universe of bungalows, family hutments and blocks of flats under construction. All this was bordered by the zone, a great stretch of wasteland running the length of the old fortifications that used to surround Paris. Grim as this environment was, it was synonymous with freedom, with “playing at setting off on one’s travels in an abandoned car-wreck.”

The Poterne des Peupliers, the Porte de Gentilly, the Vaugirard abattoirs, the tunnel of the Bievre: all these places belonged to areas of Paris that had been meticulously surveyed by Eugene Atget, for whom Doisneau felt profound admiration. It was a world in which the young Doisneau felt much more at home than in the playground of the state school: “My childhood was these wastelands. My palm tree, my baobab, was the shaft of the gas lamp … ” 12

“I took mischievous pleasure in bringing to light anything abandoned not just among people but also in my choice of backgrounds … “

Intelligent as he was, the young Doisneau detested school and its discipline. He nevertheless obtained his certificat d’etudes at eleven, and at thirteen was successful in the entrance exam for the Ecole Estienne, the Higher School of Graphic Arts and Trades boulevard Auguste-Blanqui, near Place d’Italie. He had a talent for drawing and, since he enjoyed it, chose the graphic engraving workshop. This technique of engraving a limestone surface with stonemason’s chisels and burins was already obsolescent. By the time Doisneau left the school, in the summer of 1929, his diploma was useless; the entire trade had been replaced by photomechanical methods.

He nevertheless entered one of the few surviving workshops, that of Xavier Vincent in the Marais, only to leave it because he was so bored. In late 1929 , he entered the Ullmann graphics art studio, a company specializing in pharmaceutical advertising. There. he designed lettering. By now photography was rapidly becoming an important part of advertising. Ullmann installed a little photo lab on its premises under the charge of one Lucien Chauffard, whose assistant was none other than Robert Doisneau. He therefore learned on the job, making his photographic debut with a heavy wooden camera taking 9 x 12cm plates. In fact, he had already made his earliest photographs with a folding bellows 9 x 12 field camera borrowed from his stepbrother: “I began taking photographs to make a record of things that I saw every day .. When I was a child, there was a dead tree in front of the house that I tried to draw. My earliest photos satisfied the same need. And since I was very shy and didn’t dare look at people, my attention focused on my environment.”

His first picture showed a pile of cobblestones and was followed by images of fences, manhole covers, and gas lamps. These docile subjects delighted him. Meanwhile, his work at Ullmann’s helped to refine his technique, which he further perfected, now that Lucien Chauffard had left the company, by taking his first publicity photos. His parents thought very little of photography but this new venture confirmed his belief that it, rather than drawing, would allow him to record what he saw. Moreover, “photography seemed a tiny bit wicked to me and I liked that. • His first images were unpretentious and taken for the pleasure of the thing.

But those around him took no pleasure in them at all and this made him angry. In one of his notebooks, we read: ”I’m seventeen. I’m skinny and badly dressed and learning a trade that has no future. The things by which I’m surrounded are idiotic. When I show people my pics. they all chorus that it’s just a waste of film. I don’t care; I’m not stopping for them. Maybe one day someone will find in my images something like a snigger of disgust.”

Perhaps out of pity, his uncle, the mayor of Gentilty. commissioned a photographic record of the town. Doisneau spent his earnings on a 6 x 6 Rolleiflex – a camera that was to serve him for many years to come. For him, it was a token of liberty: With my nose in the viewfinder, I looked almost reverential, it was like a genuflection, and that suited my shyness…”.

Better suited to his “fishing” technique than the Leica its competitor and the favorite camera of the “image hunter,” his Rolleiflex thus accompanied him on long meandering voyages throught banal suhurbs: here were the multiple backdrop composing his little theater. The Sunday photographer thus came into being but the professional honed his technique so efficiently that.

In 1931, Lucien Chauffard was back in contact to suggest a job as an operator with Andre Vigneau, a very famous photographer, draughtsman and sculptor. Vigneau was a man of revolutionary theories; a whole new world opened up to Doisneau, that of the artistic avant-garde. At Vigneau’s, he met painters, writers such as Prevert, and discovered in the books of photos selected from the magazine Arts et Metiers Graphiques (edited by Charles Peignot) works that he found overwhelming: shots by Germaine Krull, Andre Kertesz, Brassaï’s night photos, and pictures by Vigneau himself. From a technical point of view, Doisneau found in Vigneau a combination of masterful lighting technique with a strong sense of form, composition, and the importance of backdrops. He heard talk of the Bauhaus, Soviet cinema, Surrealism, and Le Corbusier’s urbanistic ideas: “Nowhere else did I find such an exhilarating atmosphere.”

This was more encouragement than Doisneau needed to embark on his own quest for images in the street. He took his courage in both hands and began photographing children, groups of adults. and scenes from daily life. In these unpretentious images, made for his own pleasure, he rediscovered his childhood territories. Doisneau was later to say of them: “Shyness produced a kind of censorship, making me photograph people from a distance; this produced a kind of space all around these scenes that I subsequently tried to replicate … ”

In 1932, there came a first triumph: a series of image made at a flea market was sold to and published in the daily paper L’Excelsior, one of the first media outlets to grant photography and photojournalism a significant role.