To mark the centenary of Irving Penn’s birth, The Metropolitan Museum of Art has open its doors in April to a major exhibition celebrating one of the foremost photographers of our time. With more than 200 prints on display (the majority a recent gift to the museum from The Irving Penn Foundation), the retrospective is the most substantial to date and explores every period in Penn’s prolific 70-year long career. From New York the exhibition will then travel internationally with a first stop at the Grand Palais in Paris in September.

The publication of the accompanying book Irving Penn: Centennial is an occasion in itself. Not only does it feature the largest selection of Penn photographs ever compiled, including works that have never been published, it also provides essays with a fresh intellectual understanding of the deeply private artist and the human being behind the masterful photographs. The book and exhibition are created and co-organized by Maria Morris Hambourg, who founded the Met’s Department of Photographs in 1992 and knew Penn personally, and Jeff L. Rosenheim, the department’s current Curator in Charge.

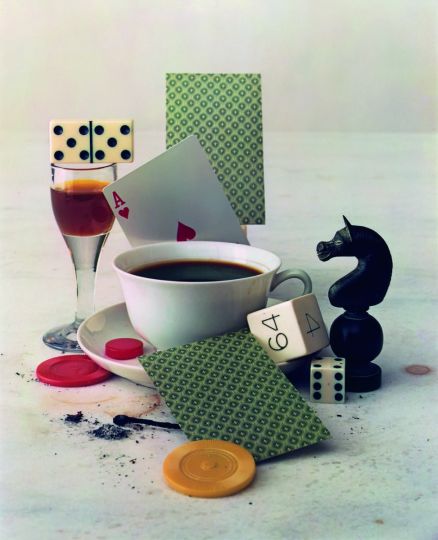

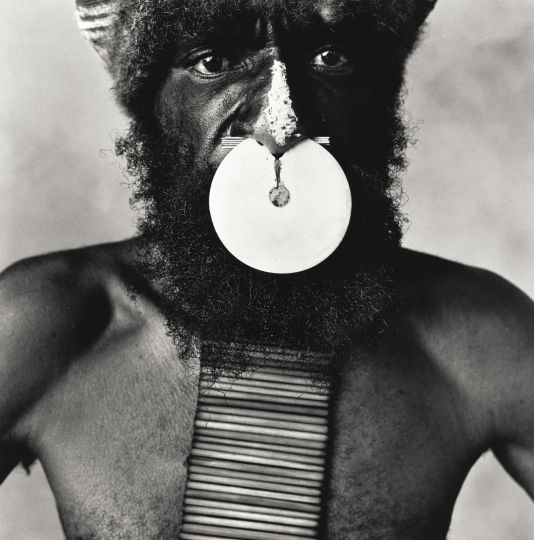

The two curators were asked to select three images each from the exhibition and reflect upon them with Luncheon magazine’s editor in chief and creative director Thomas Persson. The interviews here provide fascinating insight into the artistic creation and circumstances in which these photographs were made. From Marlene Dietrich to a tribesman in New Guinea; a female nude and a still life for Vogue; a fishmonger in London and two cigarette butts – Penn’s wide-ranging subjects were all part of his worldly narrative and, as they are observed within these pages, his profound talent for storytelling.

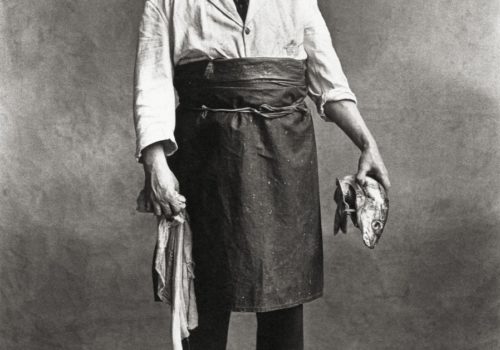

Today, we present the fourth part of this series with words on Fishmonger, London, 1950.

Thomas Persson: One of the many beautiful characteristics of Penn’s body of work is, in my opinion, that he treated all his subjects equally, be it an important cultural figure, a high fashion model, a tribesman or indeed a fishmonger. Where do you think this humane and sympathetic approach came from?

Jeff L. Rosenheim: I think it must have been from childhood, that humility, that view that all his subjects, all his work, deserved the same level of care and investigation and attention. The position that there should be a higher cultural value to one subject group than another, seems to have been an unnatural idea to Penn. All his pictures celebrate the lives of their subjects in some way. He was a type of connoisseur who took pleasure and meaning in every experience with an individual, from a chimney sweep to a tribesman in New Guinea to a fishmonger in London. He offered each the same attention with lighting and compositional strategies, and often used the same neutral backdrop seen here behind the fishmonger. This is, of course, Penn’s splendid update of the centuries old petit métier tradition, the occupational portrait tradition, but without the idiosyncratic street scenes drawn in behind the figures. Personally, I am deeply affected by the common humanity found in the Small Trade portraits from Paris, London, and New York. One question I would ask now is how important is the neutral backdrop to the success and meaning of all of his photographs? How important to Penn and his work was the discovery of the backdrop?

Thomas Persson: Because that backdrop was actually found when he first started the Small Trade series in Paris in 1950. Someone found this theatrical backdrop and brought it to Penn in the studio he had taken on rue de Vaugirard. And Penn retained it for the rest of his career…

Jeff L. Rosenheim: Yes, and that is pretty interesting. He used it in his studios from 1950 onwards. We spoke earlier about detritus. Penn made the Small Trade portraits against this backdrop, but rarely if ever does he show the edge of the fabric. However, if we look, for example, at the fashion study of Lisa Fonssagrives in the Rochas mermaid dress, or the portrait of T.S. Eliot in London against the same backdrop, Penn includes the canvas edge. He shows us the real and the artificial. And the edges are raw; they are rough. In most all of the prints Penn made from his Paris fashion photographs from 1950, the backdrop edges play a cameo role. Perhaps the best example is the mermaid dress where both edges and a small glimpse of the rest of the studio hardware are visible. This seems to be another way that Penn incorporated into the picture itself his own act of picturemaking. Curiously, he left out this trace, the edge, from the Small Trades portraits.

Thomas Persson: It is interesting that the Small Trade pictures eventually became the largest single body of work in Penn’s career.

Jeff L. Rosenheim: Although they are not explicitly catalogued or categorized as such, the Small Trade pictures really began in Peru in 1948 when Penn borrowed a local photographer’s studio in Cuzco to make portraits of workers and regional visitors to the ancient Incan city. The studio came with a neutral backdrop and one with minor painted figurative elements. When Penn opened up the studio door, in came citizens looking to pose for their Christmas portrait from the local photographer. Instead of their paying the photographer, Penn paid the sitters, a fascinating reversal that set in motion three intense days of picture making that generated some two thousand photographs. This process of discovery was then recapitulated in Paris for the small trades series. I believe that his work posing individuals who were not trained to pose — and with whom he generally could not verbally communicate — kept his eye active. The fashion models Penn worked with were professionals: their muscles were comfortable with this work and had memory. For the Small Trades pictures, Penn photographed individuals who were not comfortable posing for the camera, yet they knew how to hold the tools of their trade. So the fishmonger masterfully palms a wet, slippery fish (laughs). And just look at how beautiful is the effect. For Penn, working daily with non-fashion models in the same studio against the same backdrop as the professional fashion models, was very instructive. I know that the one informed the other. He called it ‘a balanced meal.’

Thomas Persson: Every time I look at the Small Trade pictures I am so moved by the sense of pride they show in their occupation.

Jeff L. Rosenheim: Indeed, we see very real pride in their work; Penn illuminates this in how the subjects stand and in the particular qualities and idiosyncrasies of their clothing. The latter comes from his study and instinctive understanding of the language of each garment, where it drapes, how the light reveals its form, pattern, and texture. By carefully observing the garments worn by a locomotive fireman or a coalman or a window washer, Penn learns how the body wears them and how gravity affects them.

Thomas Persson is the editor in chief and creative director of Luncheon. Jeff L. Rosenheim is the Curator in Charge at the Metropolitan Museum, in New York.

Irving Penn : Centennial

April 24 to July 30, 2017

The Met, Gallery 199

1000 5th Ave

New York, NY 10028

USA

http://www.metmuseum.org/