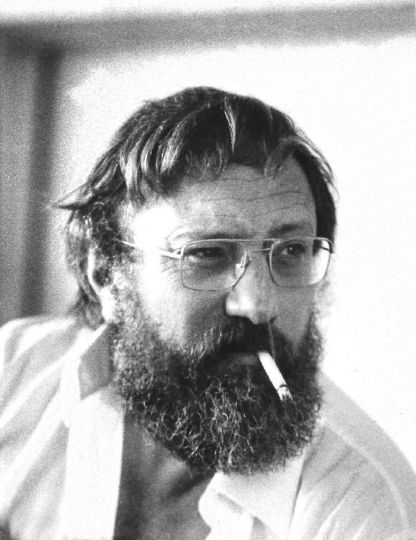

Ray was like something from another planet.

If he hadn’t believed in it, we couldn’t have done it. It was February 1986 in Arles on the Place du Forum. A cold wind was blowing through the city, intensifying the medieval shadows on the deserted streets.

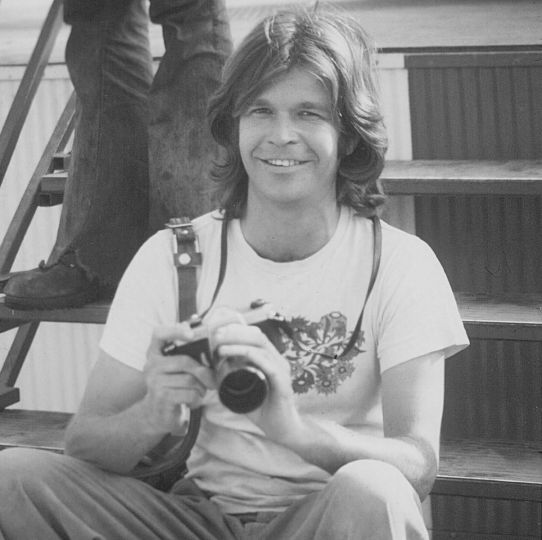

Ray DeMoulin was the new vice president of Kodak. He had come from Rochester to find out what he had gotten himself into by generously agreeing to help the Rencontres Internationales de la Photographie get back on its feet. Arles was the place where, in the coming years, photography would come into its own.

There wasn’t a trace of philanthropic naiveté in this engineer who was now in charge of the professional market, which was in disarray, while Kodak was still a triumph with the general public.

“I have to reconquer Europe,” he told me in his windowless office. “If you can get me a meeting with a professional photographer at Arles every half an hour from 7 o’clock in the morning to 5 in the afternoon, you’ll get all the funding you need.” After informing him that, given the way things worked at Arles, the schedule would more likely be from 10 o’clock in the morning to midnight, the deal was done in 30 minutes.

He was true to his word, and incredibly effective. Listening to photographers and lab reps, he kept the TriX in production, made high-quality color film and paper, and was one of the first people to take an interest in digital, going so far as to open a training center.

And all this simply by listening to the professionals he met as part of the “Day in the Life” project, then at Arles, and later around the world. The photographers appreciated having someone to talk to at Kodak, a hegemonic and slightly autistic giant.

The dinner came to an end that winter evening. The senior manager of Kodak France, who was accompanying DeMoulin and who had never been to Arles, was highly skeptical of the sight of the Atelier des Forges, the SNCF industrial wasteland which they had seen that afternoon.

This was before it was so common for factories and such to be reconverted into cultural spaces. Back then, photography wanted to be accepted by respectable museums. The day had been long, with the broken or non-existent English of the French group, and the sheer enthusiasm of our new American friend.

I asked Jean-Maurice Rouquette, president and co-founder of the Rencontres, if the key to his apartment still unlocked the doors to all the city’s monuments, for which he served as conversation officer. So there we were at 11 o’clock at night, twenty feet underground, visiting the Arles cryptoporticus, one of the rarest and finest Roman vestiges, with Jean-Maurice giving a guided tour in Latin, Provencal and slang while I “translated” what I could.

Leaving at midnight, Ray DeMoulin concluded that the wildest adventures have to be given a try. He gave us, me and my successors, an operating budget for the next ten years, which allowed us to reestablish and transform Les Rencontres until the dawn of the 2000s. He gave us wings.

The story continued with Magnum Photos and many other photo associations and photographers who benefited from his generosity and open ears.

With the input he received, the wonderful and tireless DeMoulin was successful in his reconquest of the professional market and put Kodak back on top at the end of the 20th century, which had been its century.

We liked Ray because he was friendly. He remembered everyone like a childhood friend. He liked to live, laugh and love. At Kodak, where a lot of Mormons were on staff, perhaps they never really understood that this humanity was also the key to his professional success.

We will remember him for taking a chance on photography and helping it evolve into the art it is today. We will remember him as a friend.

François Hébel

Director of the Rencontres d’Arles 1986/1987 and 2002/2014

Director of Magnum Photos (1987/2000)

Director of Foto/Industria, Bologna since 2013.