Was there ever a path so uncertain, a fortune so ill-fated? The question perplexes to the point of absurdity while rediscovering the life and work of Austro-Czechoslovakian photographer Raoul Hausmann in Cherbourg. Interested in his most creative decade, Le Point du Jour (in Cherbourg) and its associate curator Cécile Bargues are bringing to light a body of work just as brilliant as it has been ignored.

To this day, Raoul Hausman still remains unknown. A dive into the tumult of his life is not too much to ask. Born in 1886 in Vienna, Raoul Hausmann was the son of two Czech revolutionaries. At fourteen, the family fled for Berlin. He was trained in the arts by his father, an artist and curator. Photography came to him easily. At a low cost, cameras and films were taken on vacation, to weekend at the sea. At the beginning of his twenties, he discovered the Dada movement through Johannes Baader and came into Erich Heckel’s studio. He gets married for the first time, having fun on the side with Hannah Höch, one of the photomontage pioneers, and joined the artistic and intellectual circles of Berlin.

Although relatively absent from the movement’s critical and historical comments , he is one of the figureheads of Berlin Dada. Notably, Hausmann participated in the edification of the Dada movement’s philosophical thought by theorizing destruction and recomposition as artistic creation. With George Grosz, John Heartfelt, and Richard Huelsenbeck, the thinker and philosopher was the founder of the Berlin Dada Club, created in 1918, where poetry, performance, and lectures were presented. A curious jack of all trades, and a writer as much as he was a photographer or editor, Raoul Hausmann created phonemes, visual and lyrical poems where the letters are reversed, cut-up, mixed, and pronounced without opening one’s mouth or moving one’s lips. In 1920, he also organized the first International Dada Fair. He was working on the magazine Der Dada (1919) and was improving upon photomontage technique.

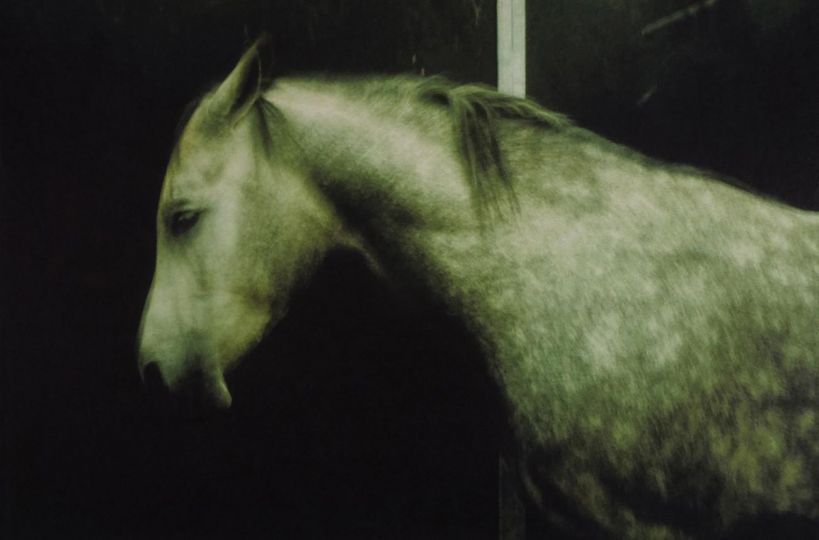

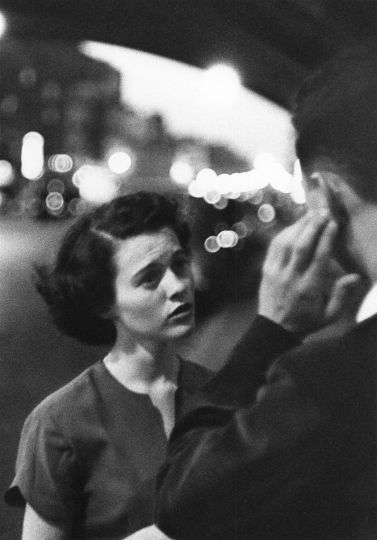

All conceived in natural light, without use of a studio or artificial light, his collages are ingenious. He wanted to found his photography on “a concordance of contraries” (Cécile Bargues). Contrary because his photographs were all radically different. Raoul Hausmann is not a dadaist experimenter, recomposing his collages of trompe-l’œils and scenes prefiguring the absurd. He is more simply “Raoul Hausmann, photographer.” Given in 1931, the title fully attests to his interest for photographic work.

At the end of the 1920s, he developed a love for the writer Vera Broido. The two quickly escaped Berlin for the Baltic and North Sea. Naked, they wandered freely on the beach. Today, the image is cliché. It is a liberation simply symbolizing the bohemian lifestyle of the time, an abandonment that we would consider loving and whole. He freezes the solid flesh, as imposing as it is elegant in its curves. Raoul Hausmann’s “concordance of contraries” must be there. His photomontages make the light dance. His nudes and portraits of fishermen immortally captured the emotions of mankind.

Up until then, everything was going well. Certainly, Hausmann exhibited only a very small amount of his photography, but the effervescence of Berlin was enough for him. The trouble started with the rise of the Nazis. Starting from 1936, Nazi Germany published the list of “degenerate art”. Cubists, dadaists, expressionists, surrealists, and those of the Bauhaus, the artists were tormented, persecuted, sometimes imprisoned. Their works were seized and destroyed. Hausmann is the thirteenth on a list comprised of dozens of others. He immediately fled to Ibiza. In a rush, he did not bring his works or archives. Everything remained in Berlin. Much would be destroyed or lost.

Ibiza is still a remote area of the world. A farming island closed off to exchange and economic capitalism, it seems to be an ideal refuge. He isolated himself in its hills and studied the fincas, rural houses and agricultural farms that populated the Balearic island. He understood these habitations as “stateless”, the fruit of cultures and long migrations from many centuries, timeless products of agricultural utility and architectural confluences. For Hausmann, there was more real modern architecture on the island than in the Berlin Bauhaus. “Raoul Hausmann, architect,” he would later write in Revue d’Anthropologie.

The Balearic islands only lasted a year. The island was the first to fall into the hands of the Francoists. Joining the republican army, he fought one month and met a bitter and brief defeat. He went to Zurich, passing though Italy, but was criticized by an architect conservator for his anarchist thinking. Asked again to pack his bags, Hausmann stopped in Prague that same year. He breathed freedom into the city. The artistic circles were very welcoming. Hausmann found his friend Moholy-Nagy and had the first monographic exhibition of his life (Museum of Decorative Arts in Prague). In 1938, Prague, like the rest of the country, was invaded by the Werhmacht. Once taken over by the Soviets in 1945, Hausmann’s work would remain long forgotten in the museum’s archives. Propaganda reversed, his work suffered. Reaching the pinnacle of absurdity, the Soviet regime took away his Czech nationality to punish the people who, in part, supported the Nazi regime.

Hausmann sought refuge in Limoges. He was sent to a camp, escaped it, and stayed in the city. He would die there in 1971, in the city’s small photo-club. What a paradoxical existence, Hausmann in Limoges! He was put up in low-income housing by the French government for war reparations. Ruined, he miraculously received donations from old friends like Gropius. Health got in the way; he was practically blind but continued his photo-collages with bits of colored cardboard pieces. Ignored in France, never exhibited while he was alive, not understood by the local population, he consistently frequented the same photo-club in the city. He seemed cut off from the world, abandoned by everyone, but, nevertheless, he corresponded with the old dadaists and Guy Debord. As inventive as he was curious, he would give Fluxus its name. “What a life!” is all one can say.

After his death, four museums would continue to expose his work: the Musée Départemental d’Art Contemporain de Rochechouart, the Berlinische Galerie in Berlin, the Musée d’Art Moderne et Contemporain in Saint-Etienne, and the Centre Pompidou in Paris. The exhibition at Point du Jour is a must-see! Cherbourg is holding a photographic treasure there, and it will travel to the Jeu de Paume in 2018. Finally, Paris will exhibit him for the first time.

Arthur Dayras

Arthur Dayras is an author specialized in photography who lives and works in Paris.

Raoul Hausmann – Photographies 1927-1936

From September 24 through January 15, 2018

Le Point du Jour

109, avenue de Paris

50100 Cherbourg-en-Cotentin

France