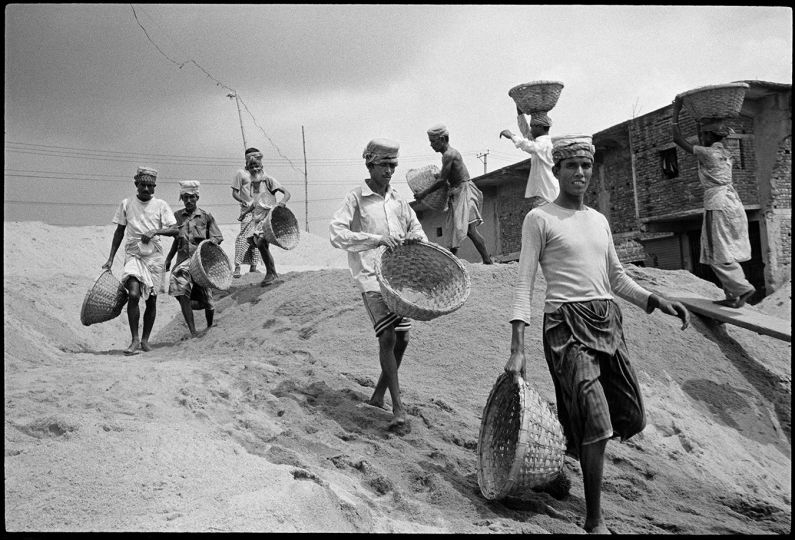

What is private in a public world delineates the distinction between the seen and unseen, a boundary that has become so stretched in the Digital Era that we might mistake it for the most elastic of plastics, the most porous of borders. For it is not that we, who were raised before the advent of digitization who must consider this brave new world, but all of those who are born into this life and will never know anything else.

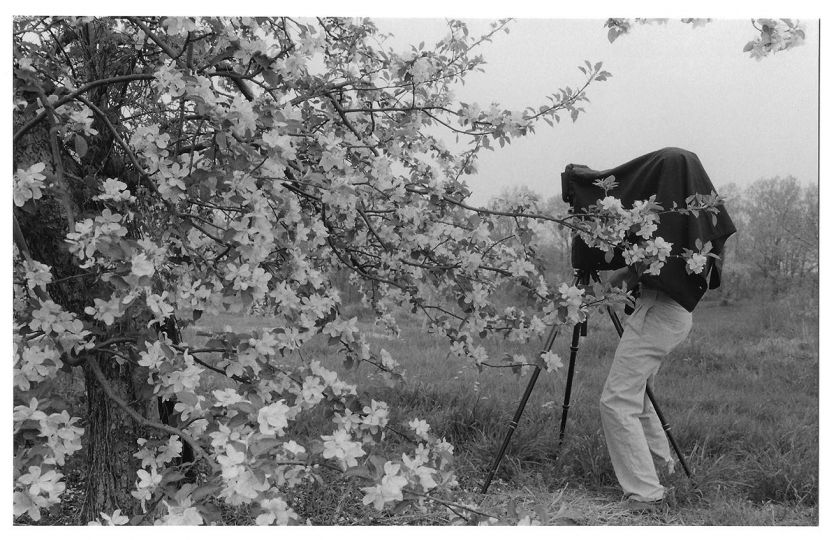

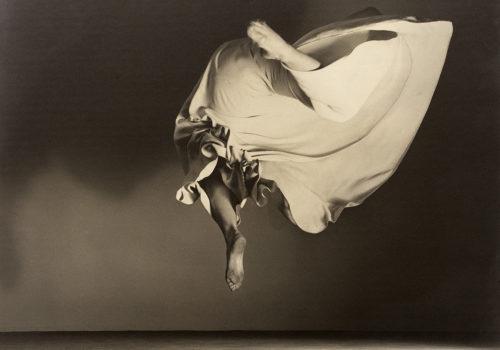

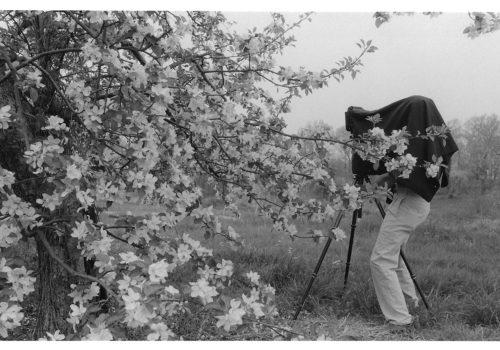

Photography has always been one means to transgress this boundary, one way inside a world we might not otherwise see, otherwise know, otherwise behold. Photography bears witness to the temporal nature of life, by transforming three dimensions into two and making the ephemeral eternal and candy for our eyes. The photograph becomes the document of that which no longer exists, but for this piece of paper, but for this scan, but for this print.

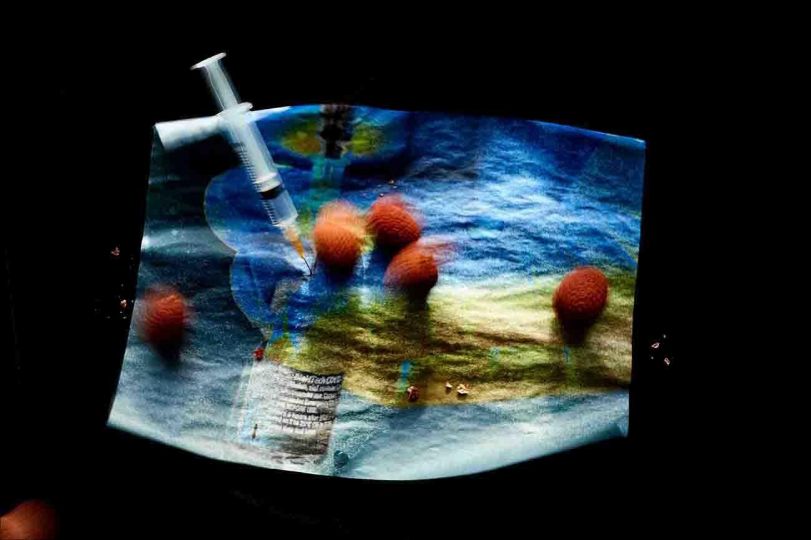

What do we really know when we expose privacy? Do we known how the other half lives, or do we catch a glimpse of our shadow selves? Do we see in the photograph of Ryan McGinley, two men embraced in a kiss as a thick viscous white liquid explodes from their mouths. Do we know what this is, or just what it is intended to be? Do we laugh, blush, giggle, or rage at this abject display of sexuality? Can we process that which is private made public if our own private matters never make the light of day? How do we respond to these borders being crossed each and every day?

Privat/Privacy (Distanz Verlag) is a beautifully produced compendium of images that question the photography in a post-privacy world. Featuring the works ofAi Weiwei, Merry Alpern, Richard Billingham, Sophie Calle, Tracy Emin, Nan Goldin, Christian Marclay, McGliney, Marilyn Minter, Mark Morrisoe, Laurel Nakate, Dash Snow and Andy Warhol, among many others, Privat/Privacy presents a series of images that push the envelope.

As Jan Verwoort writes in an essay titled, “Stepping Into and Out of the Open,” “We love the distinction between private and public. It divides social space into different spheres, creating a sense of order. Or so it seems. The downside of this distinction is that it needs to be made all the time, but can almost never be made with total clarity. For where is this magic dividing line between the spheres?” An excellent question and one that suggests privacy is a state of mind, just as a public identity is.

Because a public identity is so formally constructed, we take great care to consider it, and we hold people to expectations and roles that are meant to be fulfilled in the interest of normalcy (whatever that is). But in private, all rules can be dropped, and one can release themselves from the masks they feel forced to adopt. It is here, in this space of psychic energy that privacy holds its charms; the more repressed one feels by a public face, the sweeter rewards privacy holds. But how then do we respond to the issue of privacy made public? Or the subversion of the public sphere itself, as witnessed in the photographs of Edgar Leciejewski, whose 2010 street photographs in New York leave one with a distinct feeling of unease. He has trained his lens upon people alone in the street; yes they are out in public but were they are obviously unaware of Leciejewski’s camera. This is street photography with a curious bent as the style of the photographs evokes a surveillance video. It is the iconography of this style (the low-res imagery, the blurred faces, the casually “un-composed” frames) that remind us of the work of police and private detectives, hired to spy on their subjects.

Is street photography spying of a form? Or does it only appear this way when the iconography frames it as so? If so, is there an expectation of privacy in the public realm, or do perfect strangers have a right to our visage simply because we unknowingly entered their space?

As Verwoort continues in his essay, “[Hannah] Arendt makes it clear that under capitalist conditions, neither public nor private exist. In her view, both concepts only have meaning if they are combined in a dynamic relationship, becoming the poles between which actions move freely back and forth, a free movement within which actions move freely back and forth, a free movement within which the time and place where—according the inner logic of this action—private and public begin and end are negotiated on a case-by-case basis.”

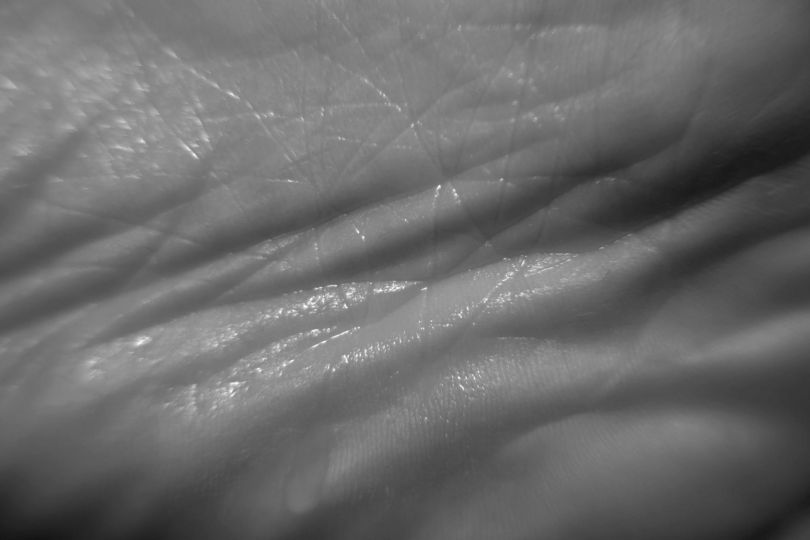

Indeed, photography negotiates this space better than most. The still image holds a power that no other form can claim. It give us a window into a world we would otherwise know but strips it from all context so that we only think we know. It gives us just enough information to hold our gaze, leading us to consider and contemplate that which speaks in all languages without uttering a single word. It allows us to feel that which we would never otherwise experience, and perhaps the more intimate this experience, the more private it feels. For intimacy is a state of mind that transports us into the private sphere.

Consider the Polaroids of Dash Snow, the at-once-familiar yet foreign world of boys gone wild. We see sex and drugs and rock and roll, and within this milieu it is the portrait of Dash snuggled in bed with his baby daughter that resonates amongst the images; and yet who is to say? This photograph was published for all the world to see, another layer added to both explore and challenge our assumptions about the nature of privacy.

BOOK

Privat/Privacy

Publisher:Distanz Verlag

Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt, Martina Weinhart, Max Hollein (eds.)

German / English

24 x 32 cm

240 pages, approx. 300 b/w and color images, softcover

ISBN 978-3-942405-89-8

Release: October 2012

39,90 €