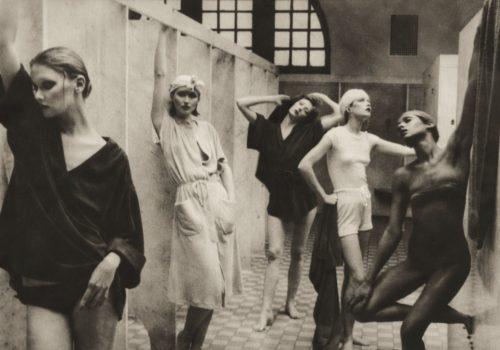

In a world inundated with icy, smooth images, the analogue photographs of Philippe Bréson are swimming against the current. He scratches, stains and cuts up his negatives to get a unique result. His reasoning is radical and transgressive and yet imbued with a kind of classicism. He reinterprets, in his own way, the great themes of the art such as landscape, the body and still-life.

How did you start taking photographs?

Philippe Bréson: When I was very young I was fascinated by the power that photography had to record and interpret the world.When I was about ten or eleven years old, I started to take some shots and working in the darkroom. images are made to meet the viewer’s imagination. The viewer has to have a part of the mystery, unspoken, a field of possibilities. I’ve been dedicated to photojournalism for about twenty years. I know the styles of documentary and news photography very well but it’s the capacities for interpretation of the medium that motivate my personal works rather than their capacities for recording.

Why have you remained attached to analogue technology?

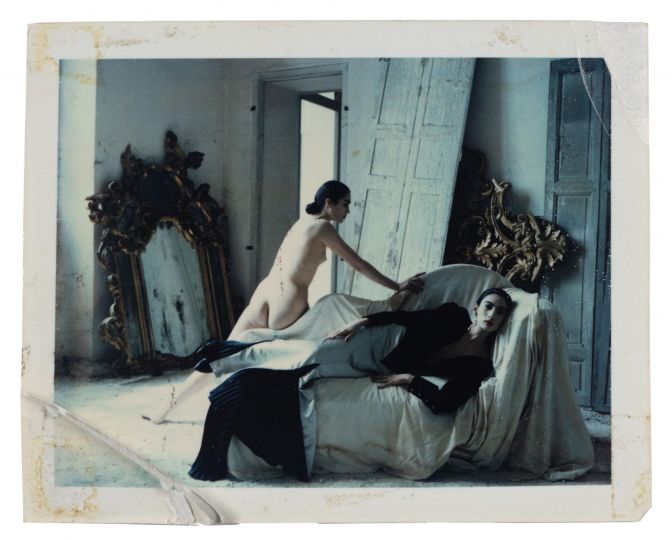

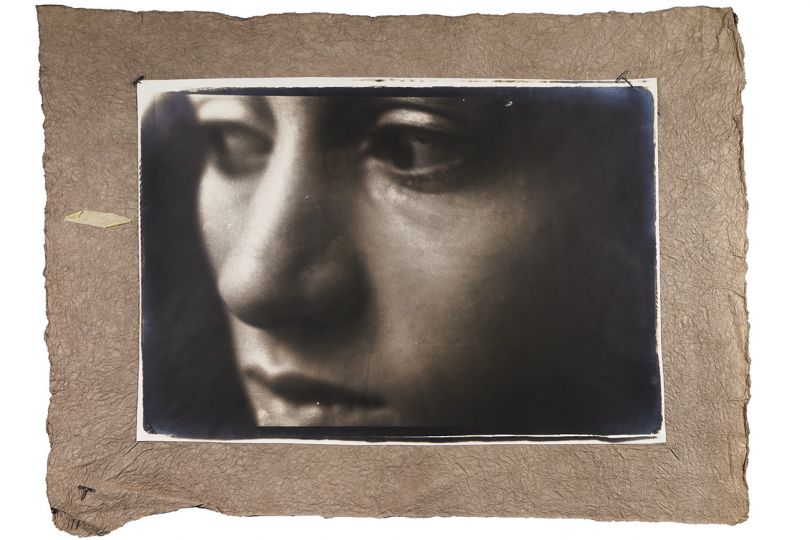

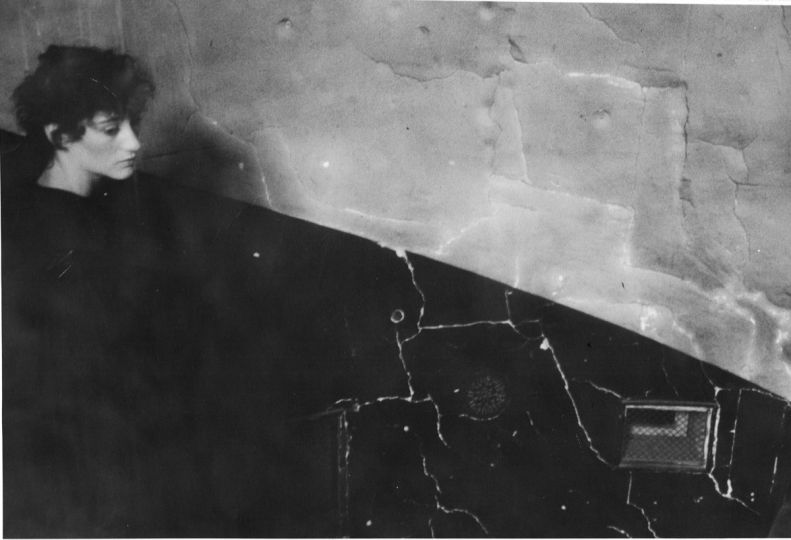

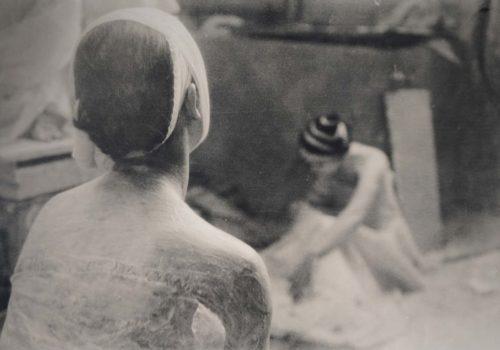

Only analogue photography allows me to interfere with the image physically. I use the negative, staining it, scratching it. I also cut it up and reassemble it. I like the irreversibility of what I make the image go through, the risk and rule-breaking that this method entails. I also use some of the old photographic processes such as gum bichromate printing, cyanotype or shooting with a pinhole camera (camera obscura) for their versatility and the dialogue they have with the history of photography. The process of silver-based analogue printing, done by hand, produces original proofs in which the hand of the artist is present. Each print is unique by its very nature and their preservation is better guaranteed than with digital prints, for which we still have a long way to go. The algorithms, the instantaneity, the breathtaking capacity for correcting mistakes that is granted by digital technology has not seduced me (yet). Photography, art of interpretation, is best for me when using the simplest, most precarious and most traditional capture device.

Can you tell me about your process for altering your photographs?

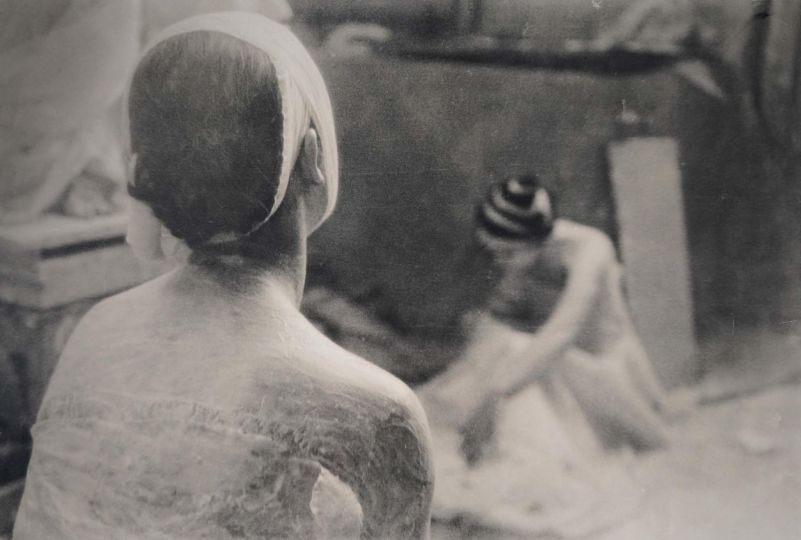

Altering the images, the work I do on the negative is something I’m very attached to, even though it’s not exclusive. It’s a layer of supplementary history that I add to the images. The negative, sensitive surface, is like the skin. The scars are the history of the owner. When I was a teenager, already passionate about photography, I used to go to the municipal library, which had a selection of photo magazines that my pocket money wouldn’t let me buy. The librarian had a mania as remarkable as mine. She used her rubber stamp to put clothes back on nude bodies. Even the slightest representation of nudity was edited out by enraged blows of her stamp. She put such energy, such precision, such steadfastness into this that it verged on being a talent. Without knowing it, she was the origin of my overindulgent love for stained and censored images. Later, I had the same emotion faced with the images of Ernest Joseph Bellocq, all of his cracked and broken glass plates that he made in the brothels of New Orleans, with the prostitutes’ faces scratched or crossed out, and the images of forensic medicine at the beginning of the century, listed and annotated.

What are your favourite themes?

My approach is not nostalgic, it is radical (it comes from the root). I explore photography’s great classical themes: the body, still-life and landscape. Contemporary dance, regularly going to the choreographer Dominique Bagouet’s studio has lead me to a conception of the body’s image that, without neglecting the aesthetics, looks first for truths: those of gesture, its place in the world, its ability to talk about the essential.

The still-lifes, that flirt with vanity or are interested in humbler objects are like breathing. In the practice of still-life there is a type of rigour and austerity that I like. With landscape, it’s not the place that motivates me but a history, a relationship with time. Since 2010, I’ve been photographing the battlefields of the First World War. I’m not a historian still less a geographer. I scratch my head at the big story. The protocol is exact: I work with maps, documents of the time and I go to the documented places, always in winter. I don’t look for remains, I try to understand the language of the landscape, its relationship with time. In a more general way, for a landscape to interest me, it has to have a real or a fantasized story. The landscape is born out of a meeting at some point between my imagination and a moment. Paradoxically, the place and its identity are not the most important components.

What influences you?

For me, the dialogue with the history of art, the consideration that using an erudite word is inseparable from an artistic practice. My influences are many and varied, they are greater than the field of photography. Of course, there’s Ralph Gibson, who was a revelation very early on. His radicalism and minimalism had a great influence on my beginnings. While I was still a teenager in my town’s photo club, where you only revered the old masters, a member uttered : “If that’s photography, let’s go, let’s do anything!” when I showed him how Gibson could photograph the corner of a white ceiling in a very moving way. I would also mention the Primitives, the expressionist cinema, the Japanese New Wave. Contemporary dance, too, is a formidably emotional machine, just like Indian traditional music. The world of Georges Bataille was also a powerful trigger. Many artists inspire me and tag along with me like Sally Mann, Joel Peter Witkin, the surrealists and many others…

Philippe Bréson, Occasional Bright Periods

Until 3rd December 2016

Galerie ARGENTIC

43 rue Daubenton

75005 Paris

France

http://www.argentic.fr/