Muriel Berthou Crestey’s book, “At the heart of photographic creation” offers a meeting with 24 of the greatest contemporary photographers.

Photographers speak. What are the regrets or surprises that punctuate a photographer’s life? What are the corresponding realization, sharing and selling strategies? What are the starting points, the theme, the forms, etc. ? What are the moods of photographers? How have new technologies changed their practices? To answer these questions and many others, Muriel Berthou Crestey met photographers representative of various movements of the contemporary era.

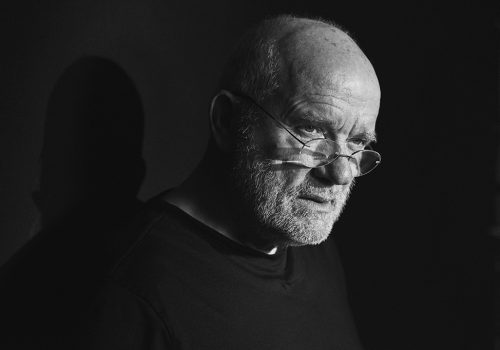

The Eye presents to you in the coming days extracts from these interviews, today PETER LINDBERGH.

The truth detector (published interview includes 24 questions – here are 6)

Muriel Berthou Crestey. You have captured the spontaneity of your nephews’ faces as children. Is that where it all started?

Peter Lindbergh. Even today, I am struck by the natural and instinctive side of childish faces. They look at the camera. It is very nice to work with them. Adults, especially when it comes to public figures, tend to overplay characters and build images before being photographed. They have a keen awareness of the appearance they project. On Saturday, I’m going to London to photograph an actor who specifically asked to be photographed on the side of his left profile, and he imposed it as a condition for this advertising campaign. The children taught me to capture the truth of people. For this, I proceed very quickly. I try to lighen up the model a bit to get an attitude that is personal. The picture is already taken before she or he has the impression that it started. It is a way of piercing the enigma that lies behind the face. And afterwards, there are choices. The photo allows this retrospective dimension to select the most advantageous and true moment.

B. C. How do you manage to bring out the authenticity of a face?

L. You can not photograph a person. It is far too complex to be reduced to a single image. What I’m trying to capture is the moment when I get in touch with her. The face of the model photographed reflects the relationship she has with the photographer when he presses the button. I recently did a “self-test” by being photographed by one of my sons (since I have four children). And it was so moving that the picture was different from the others. Usually, I do not like being photographed; I wait for it to be over. But with him, I had no apprehension. I felt completely free of my image to a point I could not have imagined. This is the proof that a photo results above all from the relationship that unites the two beings on both sides of the camera. A few days ago, I received the Amfar Award (American Foundation for Aids Research) in New York, and Robin Wright quoted a sentence from Susan Sontag in which she said in essence that photography is a matter of exchange. It’s very important to make room for others, and that’s where they give the most. I really like the people I photograph. Otherwise, it’s not worth it. And that’s the basis of everything. For me, all my photos are portrait.

B. C. The rough, cold aesthetic of the Ruhr landscapes of your childhood resurfaces very deeply. How do you envision these territories? Is this a reference that you keep in mind during your scouting?

L. These places marked me very strongly, although I do not necessarily look for industrial sites for my photographs. This has brought me a different sense of beauty. I choose mainly deserts, beaches, large indeterminate spaces that we can not locate. They offer all the freedom. We can imagine everything without being bound precisely to a setting. When you enter a cabaret in Berlin, the atmosphere is already there. I prefer that the place disappears somehow to be confused with the story I want to tell.

B. C. In fashion photos, you imagine theatrical and unusual situations that mix the world of fiction with reality. How did this desire to mix registers come to you?

L. From time to time, it is by seeing the place that the ideas appear; at other times, we look for the place that can match the plot. Both dimensions are possible. But each time intervenes this will of “starting from nothing”, of a naked space and to bring universes that transpose starting from imaginary decorations. At the beginning, when I arrived in Paris, I was fascinated by the atmosphere of a mythical and fantasized Paris, by the Café de Flore, and all the accessories like the berets … and this French side first of all seduced me. And then, I wanted to move on. So it was New York and its “raw” side, almost ugly … That’s what I like a lot. Paris has become almost “too pretty”, “too nice” …

B. C. There is a very narrative dimension in your photographs. How is the research preparatory to images?

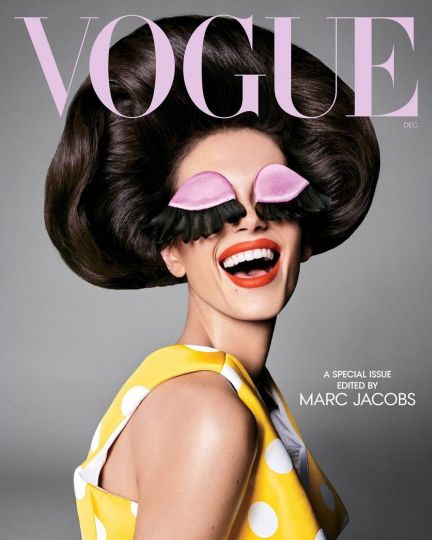

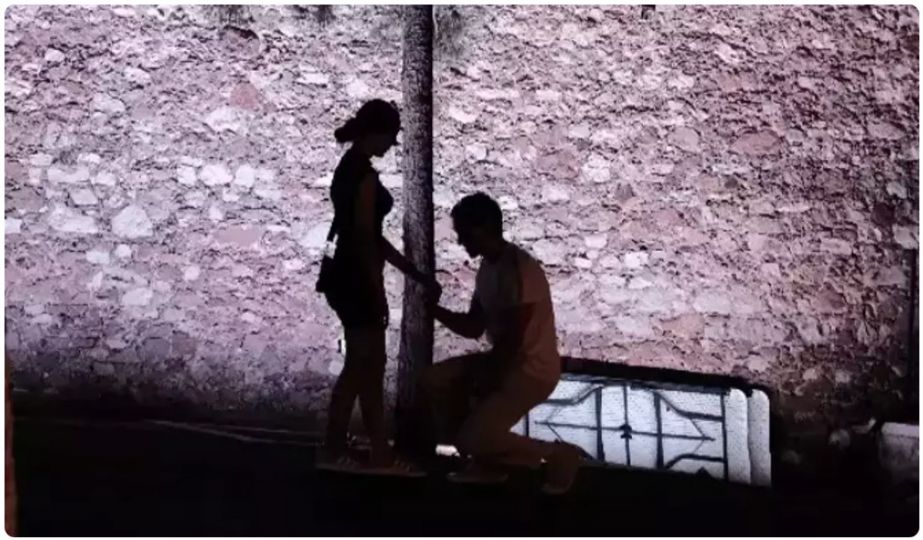

L. I write small stories beforehand, like a director preparing his film. I design scenarios each time. At the time of the MoMA’s Fashioning Fiction in Photography Since 1990 exhibition, the New York Times published an article (“Photography Review: Images of Fashion Tiptoe Into The Modern” written by Roberta Smith, April 19, 2004) stating that the beginning of this movement coincided with the series in which I brought in a little Martian in 1990 (Vogue Italia, March 1990). Obviously, he naturally fell in love with Helena Christensen; she showed him the sea, Los Angeles. They walked together on the sidewalks, in the street and a radio message asked him to leave. So, she was driving him back to the desert to join his planet. For American Vogue, I often use this type of story. Anna Wintour absolutely wanted me to come back to Vogue for this narrative aspect of my work. But the plot is also decided during the shots. At every scene, ridiculously, they change clothes. The story is very precise and takes place until very late. The sun is already down. I really like night scenes. More generally, I work mainly at night. I like the time between 11 pm and 4 am when everything is quieter and conducive to concentration.

B. C. What are your references, your influences?

L. Of course, my taste for black and white certainly comes from Fritz Lang, Metropolis, etc. It was only when I left for Duisburg to prepare for my military service, and then when I returned to the School of Fine Arts in Berlin, that I began to build up my current culture. I did not remember anything from the previous period. When we have children, we want to be able to provide them with references that will serve them later. We want them to watch this or that film. But that does not help, finally. It must come from oneself. They are like doors that are opened, gradually, where a whole imaginary is built. But everything influences me in general.

Muriel Berthou Crestey – Au coeur de la création photographique

ISBN 978-2-8258-0285-4

Editions Ides et Calendes