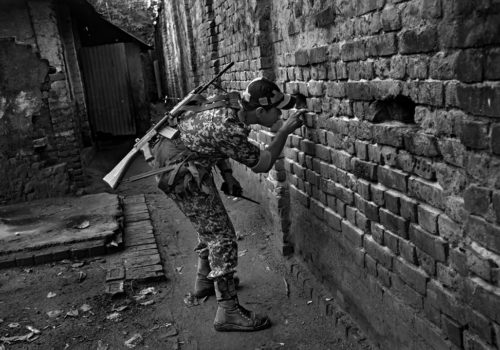

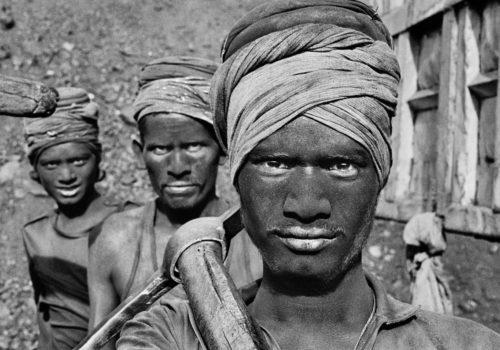

Over two thousand miles of barbed wire, brick and cement separate Bangladesh from India. Completed in 2007, the wall’s official purpose is to prevent immigration and fight against trafficking and other independence movements. The walls is dangerous—someone dies there every five days—and highly guarded by armed forces from both countries. Gaël Turine (Agence VU) traveled the entire distance of the wall in 2012 and 2013.

How did you get the idea for this story? Did you already know about the India-Bangladesh wall?

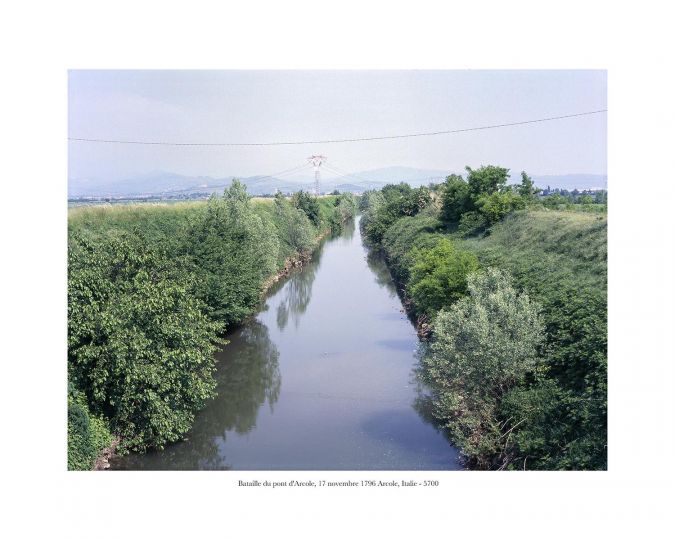

I wanted to work on the idea of separation between people and countries, particularly in a region where a physical element of separation has been erected. I avoided the better known walls to focus on the ones we never talk about. I only learned about this wall while conducting research on the internet. Its tragic details convinced me that it was my “duty” to tell this story.

How did you prepare your report from Belgium?

Mainly on the internet and by contacting Odhikar, a human rights NGO based in Dhaka, the capital of Bangladesh. They know the subject well, and a few years ago they released a report on the wall and the atrocities committed there.

Do you feel powerless? Are you trying to raise awareness, or change something with this work?

Not since the Middle Ages have so many walls been built or renovated. It’s appalling, and says much about the current state of nationalism, security and our lack of solidarity. It will already be something if, as a photojournalist, I can call attention to what’s happening at the wall, through exhibitions, publications and their subsequent coverage in the media. Afterwards, it will be up to individuals and communities to react. I don’t think that my report will effect a change, but everyone who sees the exhibition, reads the book or an article about it will be one more witness.

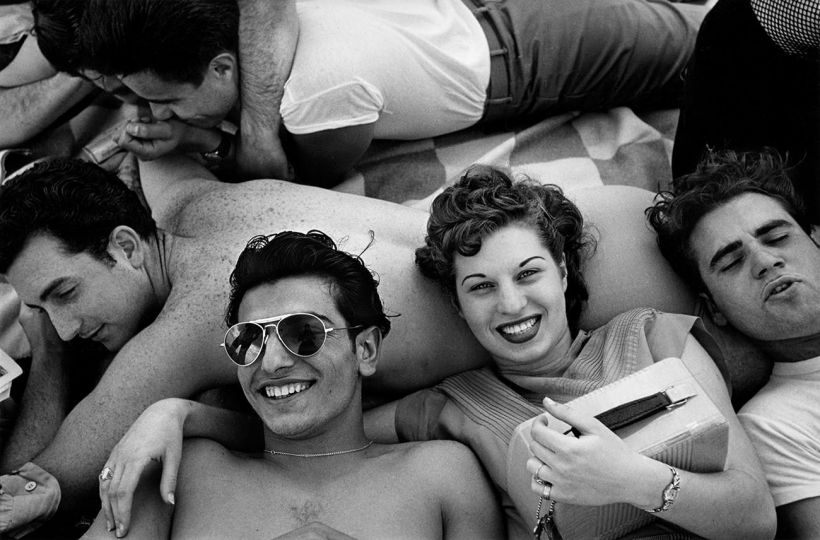

You have written that, for the Bangladeshis attempting to cross the wall, “the dream of a better life outweighs the danger.” Are they justified in this belief?

Unfortunately, many Bangladeshis continue to believe that life will be easier in India, despite the harsh welcome they receive there. The opportunities are greater, and the salaries, while very low, are higher than in their native country. India is not, in my opinion, a paradise for the Bangladeshis, nor is Europe a paradise for immigrants from Eritrea, Afghanistan, Syria and the Congo. But how can you deny that it’s worse—much worse— for them in Bangladesh? How can you tell them that it’s better to stay home? Anyway, that’s a very complex debate. The risks of crossing the wall are well known, as are the risks of crossing the Mediterranean on makeshift boats. But that risk will never damped their desire, their need, to flee war, famine, dictatorships and poverty. The number of immigrants is rising. So is the number of walls.

How was it on the ground? Were you able to move freely? Did you stay near the wall?

I made four trips, two on each side of the wall. With the help of Odhikar activists, I was able to visit several border villages and we tried, where possible, to enter the restricted areas on each side of the wall, meeting with victims and the families of victims of the repressive military border control. Freedom of movement is limited and we were only able to shoot about 5% of the time on site. We spent most of our time figuring out how to bypass checkpoints, meeting with families, and figuring out how to travel during rainy season.

Read the full article on the French version of L’Oeil.

EXHIBITION

Le mur et la peur de Gaël Turine

Galerie FAIT & CAUSE

Through February 28th 2015

58 Rue Quincampoix

75004 Paris

BOOK

Le mur et la peur de Gaël Turine

Photo Poche

Editions Acte Sud