“The camera is a strange instrument. It demands, first of all, that you see coherently. It makes it possible for you to enter into worlds, and places, and associations that would otherwise be very difficult to do.” – David Goldblatt

Pace Gallery presents David Goldblatt: Strange Instrument, an exhibition that brings together more than 60 photographs documenting South Africa—where Goldblatt was born in 1930 and lived until his death in 2018—at the height of apartheid, between the early 1960s the end of the 1980s. Curated by artist and activist Zanele Muholi, who was Goldblatt’s friend and mentee, the exhibition offers a deeply personal meditation on the brutality and humanity that Goldblatt captured in his strikingly beautiful images of everyday lives under conditions of profound injustice. Strange Instrument—on view February 26 – March 27, 2021—marks the first time that Muholi has engaged with Goldblatt’s work since his passing in 2018. Taking an expansive and affective approach to their mentor’s body of work, the exhibition presents a portrait of Goldblatt himself through Muholi’s eyes.

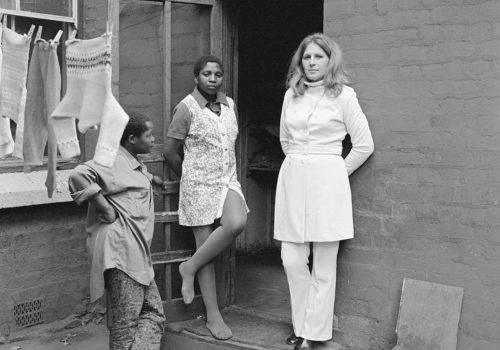

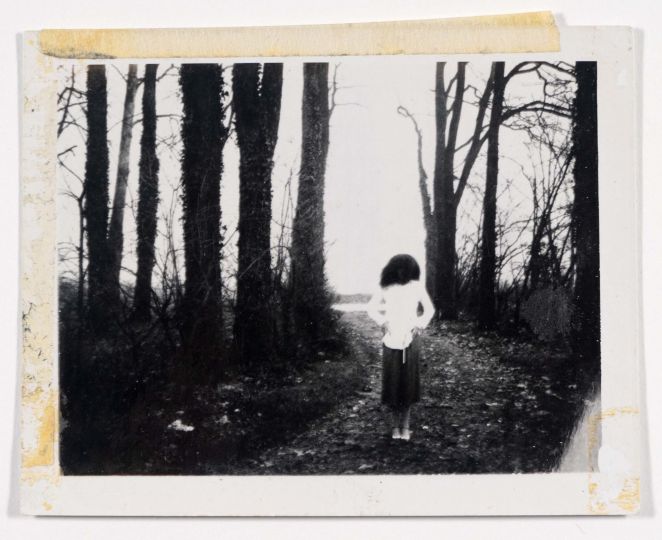

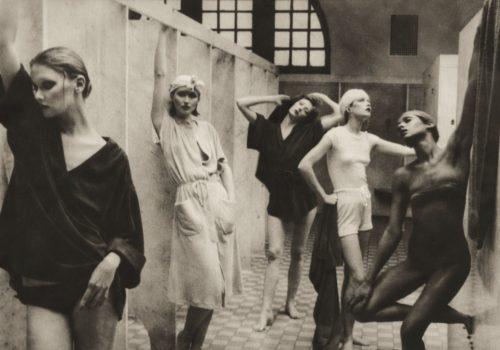

Surveying the diverse range of Goldblatt’s output, the show encompasses portraits and street scenes shot on the corners and parks of Johannesburg and other cities, as well as in neighborhoods and segregated townships where black and “colored” communities lived. Many such locales were later subjected to systematic demolition and dispossession of land, making Goldblatt’s photographs some of their only existing documentation. Such scenes are interwoven with images of commerce, architecture, mining, religion, leisure, and domestic life. The earliest image in the exhibition dates to 1962—just over a decade after the segregationist National Party rose to power in South Africa—and the latest work dates to 1990, the year that anti-apartheid revolutionary Nelson Mandela was freed from prison. Goldblatt did not consider himself an activist and never set out to make political work or anti-apartheid “propaganda”; however, he was always clear about his mission to expose the social and interpersonal reality of South Africa’s policies. “I will not allow my work to be compromised,” he once declared, “I comprise every day just by drawing breath in this country.”

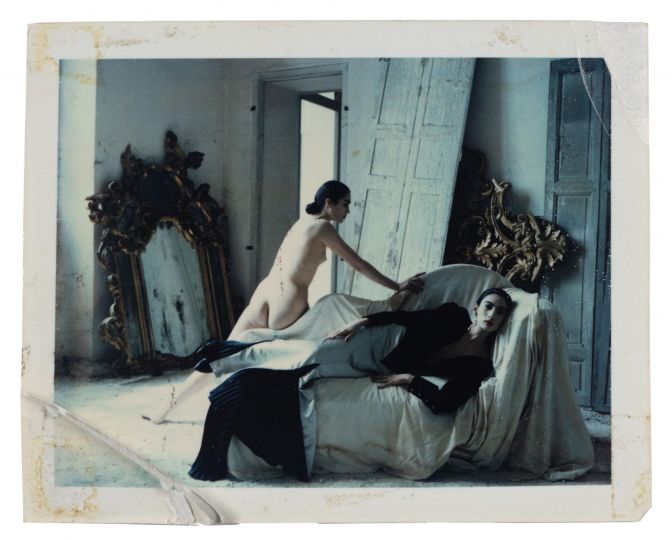

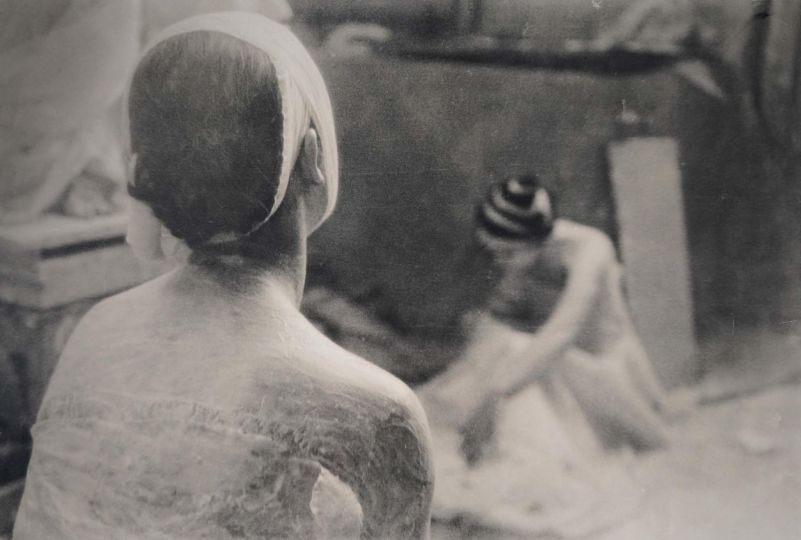

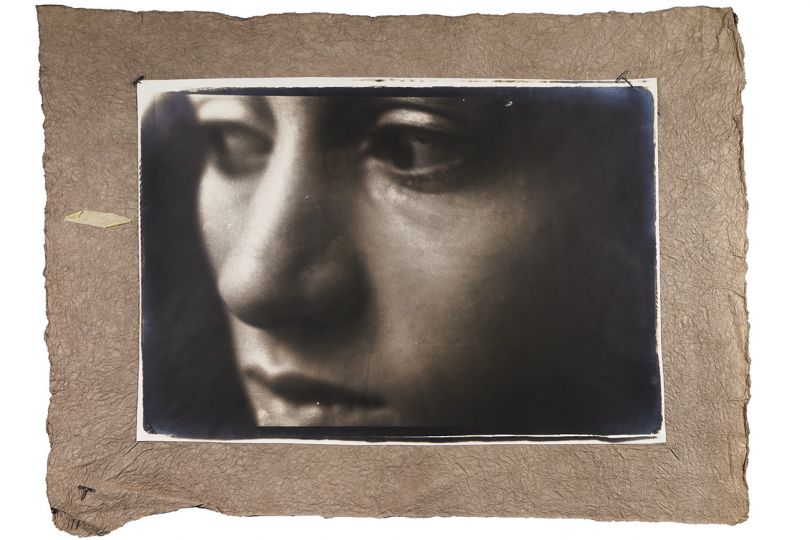

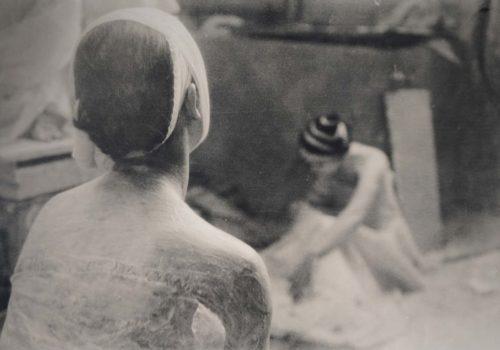

Muholi first became aware of Goldblatt in the early 2000s through their involvement in the Market Photo Workshop—a creative community, gallery, and school in Johannesburg dedicated to contemporary photography, which Goldblatt helped to found. Influenced by Goldblatt’s Particulars series—which features extreme close-up crops of bodies— Muholi struck up a friendship with the renowned photographer, though they were separated in age by more than five decades. “David became more than just a [mentor], he became a friend and a father figure,” Muholi recalls, “He was a chosen person in my life who made a huge difference.” Although Goldblatt’s body of work spans more than seven decades, the exhibition concentrates on the South Africa of the 1970s and ‘80s—the world in which Muholi themself came of age.

Equal parts artist and documentarian, Goldblatt was known for his practice of attaching extensive captions to his photographs, which almost always identify the subject, place, and time in which the image was taken. These titles often play a vital role in exposing the visible and invisible forces through which the country’s policies of extreme racism and segregation shaped the dynamics of life, especially along axes of gender, labor, identity, and freedom of movement. Beyond endowing his images with documentary power, Goldblatt’s titles also dignify the people and places he photographs. To balance the authoritative weight of Goldblatt’s captions, Muholi has grouped the works in the show into 23 idiosyncratic categories of their own devising—on subjects such as “Nurturing,” “Sleep,” “Friendships,” “Textures,” “Poverty,” and “Pulse”—which reflect their own individual response to the image alongside the historical information contained in the caption.

Goldblatt’s images rarely picture outright violence or exploitation, but more often capture the subtleties and nuances of apartheid’s insidious effect on the mundane existence of communities of color. The formal beauty of the images is often a mechanism for rendering palpable the sinister ways in which apartheid infiltrated even the most private and mundane aspects of social existence. “A common response from potential publishers was: Where are the apartheid signs?” Goldblatt once recalled of his efforts to publish his work abroad: “To me, [apartheid] was embedded deep, deep, deep in the grain of those photographs. People overseas simply didn’t grasp these extraordinary contradictions in our life.” While Goldblatt’s ability to gain access to and make photographs in such a wide range of contexts is partly what allowed him to produce such an extraordinary and influential body of work, it also reflected his privileged status as a white person under conditions of strict racial segregation. No black photographer could have moved so easily through such a diversity of social spaces. As a Jewish person, Goldblatt meanwhile existed apart from the dominant white community of Afrikaaners, and often described feeling internally like an outsider—a self-alienation that sharpened his critical gaze.

For Muholi, Goldblatt’s work points us to the fact that ultimately, “photography is about accessibility.” How do images grant access to the lives of others, to vital yet problematic histories that time threatens to erode, and to stories and experiences that might otherwise have been rendered invisible? Access is also a marker of privilege, an index of who possesses the power to make such documents, to wield the camera, to capture a photograph: “How were these images taken really?” Muholi asks of Goldblatt’s portraits of anonymous people in the markets and parks of Johannesburg and Transkei. “How do they speak to the South African archives? […] I, as a black person, would not have had access to those spaces and the people that [Goldblatt] had the opportunity to photograph.” Muholi

describes this exhibition as an effort to explore the “living memory” of Goldblatt, which continues his lifelong project of exposing conditions of injustice and oppression—those “extraordinary contradictions”—which did not disappear with the formal end of the apartheid regime.

David Goldblatt (b. 1930, Randfontein, South Africa; d. 2018, Johannesburg, South Africa) chronicled the structures, people and landscapes of South Africa from 1948 until his death in June 2018.

Well known for his photography which explored both public and private life in South Africa, Goldblatt created a body of powerful images which depicted life during and following the time of apartheid. Goldblatt also extensively photographed colonial era and post-apartheid monuments, buildings, churches, signs, ruins, and other imprints on the South African landscape made by society with the idea that structures reveal something about the values of the people who built them.

In 1989, Goldblatt founded the Market Photography Workshop in Johannesburg to provide further education in visual literacy to students disadvantaged by apartheid. In 1998 he was the first South African to have a solo exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York and in 2016, he was awarded the Commandeur des Arts et des Lettres by the Ministry of Culture of France.

David Goldblatt : Strange Instrument

Curated by Zanele Muholi

in collaboration with Yancey Richardson Gallery

Pace Gallery

February 26 – March 27, 2021

540 West 25th Street

New York