Recently presented at the International Center of Photography and now available for travel, “Capa in Color” presents Robert Capa’s color photographs to the European public for the first time. Although he is recognized almost exclusively as a master of black-and-white photography, Capa began working regularly with color film in 1941 and used it until his death in 1954. While some of this work was published in the magazines of the day, the majority of these images have never been printed or seen in any form.

“Capa in Color” includes over 150 contemporary color prints by Capa, as well as personal papers and tearsheets from the magazines in which the images originally appeared. Organized by Cynthia Young, curator of Capa Collections at ICP, the exhibition presents an unexpected aspect of Capa’s career that has been previously edited out of posthumous books and exhibitions, and show how he embraced color photography and integrated it into his work as a photojournalist in the 1940s and 1950s.

Robert Capa’s (1913–1954) reputation as one of history’s most notable photojournalists is well established. Born Endre Ernö Friedmann in Budapest and naturalized as a U.S. citizen in 1946, he was deemed “The Greatest War Photographer in the World” by Picture Post in a late 1938 publication of his Spanish Civil War photographs. During World War II, he worked for such magazines as Collier’s and Life, extensively portraying preparation for war as well as its devastating aftermath. His best-known images symbolized for many the brutality and valor of war and changed the public perception of, and set new standards for, war photography.

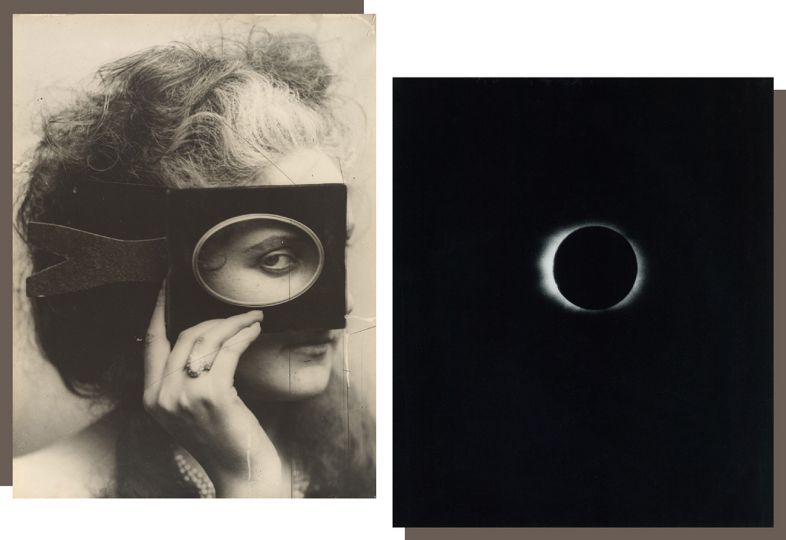

July 27, 1938, while in China for eight months covering the Sino-Japanese war, Robert Capa wrote to a friend at his New York agency, “… send 12 rolls of Kodachrome with all instructions; … Send it “Via Clipper” because I have an idea for Life“. Although no color film from China survives except for four prints published in the October 17, 1938, issue of Life, Capa was clearly interested in working with color photography even before it was widely used by many other photojournalists.

In 1941, he photographed Ernest Hemingway at his home in Sun Valley, Idaho, in color, and used color for a story about crossing the Atlantic on a freighter with an Allied convoy, published in the Saturday Evening Post. While Capa is best known for the black-and-white images of D-Day, he also used color film sporadically during World War II, most notably to photograph American troops and the French Camel Corps in Tunisia in 1943.

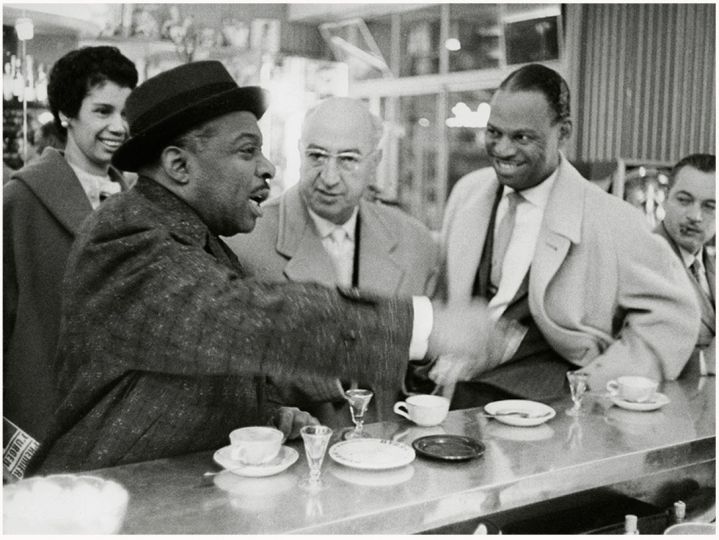

Capa’s use of color film exploded in his postwar stories for magazines such as Holiday (USA ), Ladies’ Home Journal (USA ), Illustrated (UK), and Epoca (Italy). These photographs, which until now have been seen only in magazine spreads, brought the lives of ordinary and exotic people from around the world to American and European readers alike, and were markedly different from the war reportage that had dominated Capa’s early career. Capa’s technical ability coupled with his engagement with human emotion in his prewar black-andwhite stories enabled him to move back and forth between black and white and color film and integrate color to complement the subjects he photographed. These early stories include photographs of Moscow’s Red Square from a 1947 trip to the USS R with writer John Steinbeck and refugees and the lives of new settlers in Israel in 1949–50. For the Generation X project, Capa traveled to Oslo and northern Norway, Essen, and Paris to capture the lives and dreams of youth born before the war.

Capa’s photographs also provided readers a glimpse into more glamorous lifestyles that depended on the allure and seduction of color photography. In 1950, he covered fashionable ski resorts in the Swiss, Austrian, and French Alps, and the stylish French resorts of Biarritz and Deauville for the burgeoning travel market capitalized on by Holiday magazine. He even tried fashion photography by the banks of the Seine and on the Place Vendôme. Capa also photographed actors and directors on European film sets, including Ingrid Bergman in Roberto Rossellini’s Viaggio in Italia, Orson Welles in Black Rose, and John Huston’s Moulin Rouge. Additional portraiture in this period included striking images of Picasso, on the beach near Vallauris, France with his young son Claude.

Capa carried at least two cameras for all of his postwar stories: one with black-and-white film and one with color, using a combination of 35mm and 4×5 Kodachrome and medium-format Ektachrome film, emphasizing the importance of this new medium in his development as a photographer. He continued to work with color until the end of his life, including in Indochina, where he was killed in May 1954. His color photographs of Indochina presage the color images that dominated the coverage from Vietnam in the 1960s.

“Capa in Color” is the first museum exhibition to explore Capa’s fourteen-year engagement with color photography and to assess this work in relation to his career and period in which he worked. His talent with black-andwhite composition was prodigious, and using color film halfway through his career required a new discipline. “Capa in Color” explores how he started to see anew with color film and how his work adapted to a new postwar sensibility. The new medium required him to readjust to color compositions, but also to a postwar audience, interested in being entertained and transported to new places.

CURATOR: Cynthia Young, curator of the Robert Capa archives.