By the time Olivier Rebbot started photographing child prostitutes around Times Square, the city was going to hell. Forget the phony graffiti-airbrushed disco nostalgia. In the spring of 1977, New York was a rat-infested, shit-smeared, crime-ridden, vandalized sleazepit. “This town’s in tatters,” Mick Jagger sang on that year’s Shattered — which is as perfect a theme song for the era as there is — and it was only getting worse. The spring was turning into summer, and that summer it would all burst open, the Summer of Sam, the summer of the blackout and of the looting and of the Bronx on fire.

Olivier wasn’t yet 27. He’d been trying to make it as a photographer in New York for five years but he was struggling, drifting among small, long-defunct agencies. He caught a few assignments from a friend at a German publishing house, spent an unhappy year working as an editor for a Brazilian magazine to make ends meet, and went from story to story — women in the army, an earthquake in Guatemala, a dictator in Panama, the American bicentennial and presidential campaign — but nothing much came of it. While his buddies snagged contracts with Time or Newsweek, he hung around the edges, worked on spec, and here and there sold a quarter-page picture to a magazine in France or Spain.

That’s when he began making pictures on 42nd Street.

Maybe he was thinking of a feature, like those he’d recently done on Harlem and Nashville. Or maybe he’d just watched the film Midnight Cowboy. Or maybe his poverty reminded him of when he dropped out of school and moved to Marseilles and lived in the red-light district with all the whores, the matronly women who took a liking to this sixteen year-old kid on his own. Or maybe, after visiting the New York Times building one day, hustling for work, he was on his way to the subway station entrance on 42nd and 7th and ran across the real hustlers around the corner.

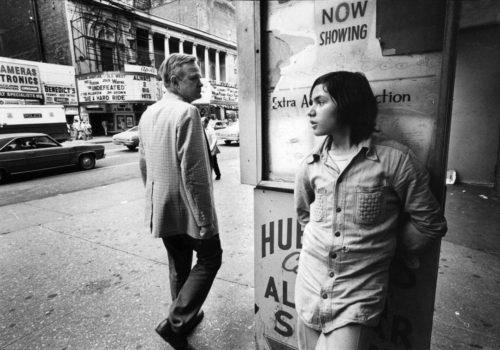

All we know for sure is that at the city’s most depraved moment he chose to photograph its most depraved location, Times Square, once a tourist must-see, but where now boys as young as eleven hung out in front of the old Hubert’s Museum and Flea Circus waiting to be picked up by the old guys they called “pigeons.”

For the last couple of months I have been studying the contact sheets in the old-school way — with a loupe and a lightbox. I’d looked at them many times before, back when I worked at Contact Press Images where they ended up, but I’ve decided to re-edit them. More than forty years have passed since they were shot, and if I’ve learned anything from being buried in pictures for a good part of those decades, it’s that time changes how we see, what we see, what’s interesting or beautiful or — as in this case — appalling.

There are 49 contact sheets altogether — about a thousand frames. They are numbered but the numbering came later, after Olivier died in 1981, and the rolls of film are not in order. There are no captions, but checking the release dates of the movies on the marquees (there were ten theaters on this stretch of 42nd Street) shows that almost all the pictures were made in the spring and early summer of 1977, and only a few, a year later in the summer of 1978.

We know, too, that Olivier had started working on the story by May 24, 1977, because on one of the contact sheets he’s photographed a man sprawled on the sidewalk (dead or dead drunk, who knows?), and the man is lying on a copy of the Daily News with the headline “Cauthen Injured in Spill” — referring to 17-year-old Steve Cauthen, the wunderkind jockey who’d just been in a three-horse crash at Belmont Raceway (and who Olivier would photograph coincidentally six months later, fully recovered).

Almost all the pictures are made in the same area — amongst the movies and adult bookstores and souvenir shops surrounding the Playland Arcade that occupied the street level of Hubert’s on the south side of 42nd Street. The arcade had been there since the 1940s, and amid the skeeball and pinball machines and steering wheels and periscopes and rifles you could still watch the first fight between Joe Louis and Jersey Joe Walcott on an antique Nickelodeon. The old signage was still there, too — “Hubert’s continuous ALL STAR show in rear.”

Going through the contact sheets, I slowly piece together a mosaic of the block as it was: the line of theaters interspersed with cheap shops and cheap food. The movies are a dizzying mix of blockbusters, blaxploitation, monster movies, Kung Fu, and porn, with titles like Eaten Alive and Nazi Love Camp on the marquee next to Star Wars or, in an example of art imitating life, Taxi Driver — in which the city on screen looks a lot like the one on Olivier’s contacts.

There’s a whole world here: a black evangelist woman preaching on the corner wiping her eyes, a cop with a mustache playing pinball, the loser of a fist fight reeling backwards, blood rushing from his nose. And everywhere, in nearly every frame, there are boys. Dozens of them. Boys as young as ten swirling around the mouth of the arcade all summer long in shorts and tube socks, clutching boom boxes.

The pictures can be selected to make them look sad, but mostly on the contact sheets they are not sad. They’re friends. They’re a gang. They joke around. They play arcade games. They show off. They do karate moves. They do backflips.

Since there are no captions, we don’t know their names, or who they are, or what became of them. All we know is what we see, what Olivier shows us. And what he shows us, repeatedly, is young kids having fun together, then being approached by older men, either inside of the arcade or out front, an instant of body contact — an arm draped over a boy’s shoulder, a head leaned in — followed by what seems to be a suddenly serious conversation, after which the pair, tall and short, disappear from the frame.

All this takes place in broad daylight, in plain view. The cops, the store owners, the kids themselves — no one seems to care.

Ten boys show up in at least twenty of Olivier’s images. But there are two who make an appearance in over a hundred frames apiece. I call them Horatio and Bobby.

Horatio is the smallest, probably the youngest. He might be Hispanic. His pants are too big and in any frame without other boys, he seems lost in the city, Lilliputian. You can understand why Olivier would focus on him. He’s the picture of vulnerability. Seeing him with an older man, you long to believe that the man is his father. But then there are other men and that’s the end of that.

Bobby is small too. He’s white and looks like kids in my seventh grade class (I was thirteen that year). He has long feathered hair and he’s thin and light and brash. He’s the one wrestling with his friend on the sidewalk, climbing up a lamp pole, a bundle of energy.

Olivier may have hoped a headlong dive into New York’s dark side would save him professionally — and although he wasn’t altogether wrong it wouldn’t be this story. The New York Times, in whose actual physical shadow all of this was taking place, refused to run it (five pictures did run in a Swedish magazine, and two in Paris-Match.) Instead, a few weeks later, when the summer was at its hottest, the dark energy finally swelled then broke like a wave when the temperature shot up and the power went off and the city went crazy, and hundreds of buildings in the Bronx went up in flames, and roving mobs smashed and looted stores in Brooklyn.

Olivier was there for that, the looting, and his pictures were picked up by Newsweek and then he was picked up by Newsweek and his wish came true. He was on assignment. Constantly. The next twelve months took him to Libya, Egypt, and Senegal, and then to wars in Nicaragua, and Lebanon, and after that he was off, covering hotspots that kept getting hotter until he was shot in El Salvador in January 1981 and it killed him.

I live fourteen blocks from where these images were made and I recently walked over there to have a look. Many of the buildings in Olivier’s images have long since been demolished, replaced by billboard-covered glass monstrosities that, post-pandemic, look ready for demolition themselves. It’s a trashy tourist street. There’s a Dave and Busters, a Madame Tussauds and, by the quirk of that genetic disposition that attaches itself to a place, at the very spot where Hubert’s Museum Flea Circus once stood, the Ripley’s Believe it or Not “Odditorium.”

The Empire Theater, which had been next door to Hubert’s, is still here, although just the facade, and it’s further down the block, having been moved during the redevelopment of the 1990s. It’s the AMC Empire 25 now, where they’re showing the new Spiderman.

Olivier came back here once more after that summer. By then a year had passed and Playland was gone, transformed into “Peepland” which advertised “Live Nude Girl Models” and had an entrance shaped like a keyhole. The boys were gone, too — all except for Bobby, who Olivier runs into on the opposite side of the street. He’s changed, too, is taller, less cute than handsome, and wears a checkered shirt open to the waist and a leather wristband. He smokes.

He and Olivier spend the afternoon together — along with a group of Bobby’s friends. Olivier’s Leica tracks them as they cross the street to Peepland, and as he treats them to some food at a lunch counter. Then it follows them under the marquee for Grease as they walk west to the McCaffrey Playground on 43rd, where Bobby smokes a joint, while his buddy goes flying on a swing set fifteen feet in the air.

At the park, one of the kids takes Olivier’s picture. He’s wearing the same clothes he wore in Lebanon — tan shirt, tan cargo pants and parachutist boots — and although he has a reputation as a bon vivant, always smiling and joking, he now stares at the camera glumly. His sister, Sylvie, who was in New York at the time, remembers him coming back from photographing the boys and actually throwing up. “To him the relationship of those older guys looking for young boys was totally, totally sickening.”

On the last contact sheet — of the day, and of the whole project — we see Bobby pull a brush through his hair, then he and his friends head back to 42nd Street, passing apartment building stoops. Bobby crosses Eighth Avenue, walks to the corner, and folds his arms on top of a mailbox, staring out towards Port Authority. He looks somber, lost in thought. Then Olivier gets behind him and we see people streaming past and, in the last images, an older man growing larger in the frame.

Jacques Menasche

instagram: jacquesmenasche

A documentary on the life and work of Olivier Rebbot is currently in post-production. A gofundme campaign has been created by Sylvie Rebbot, Olivier’s sister ex director library Magnum Photos, director photography magazine GEO contributor L’Oeil de la photographie , to help finance its completion. You can contribute at https://www.gofundme.com/f/cacjec-olivier-rebbot-documentary-fund