With around twenty new photographs, this larger edition of Roots, initially published in 2012 by Xavier Barral and quickly out of prints, immerses us in Belgium in the 1970s to 1980s. From the first photographs in black and white, giving way to color, this book explores the extremely particular universe, almost expressionistic, of the Belgian photographer. Here he talks about it openly.

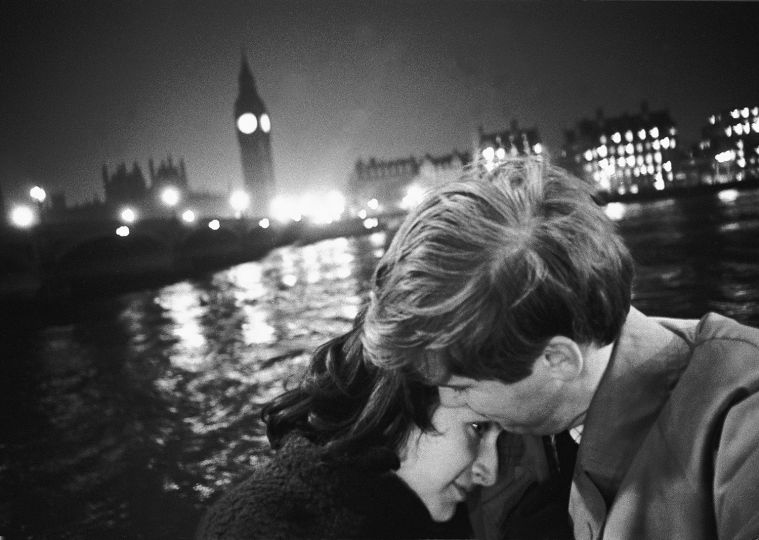

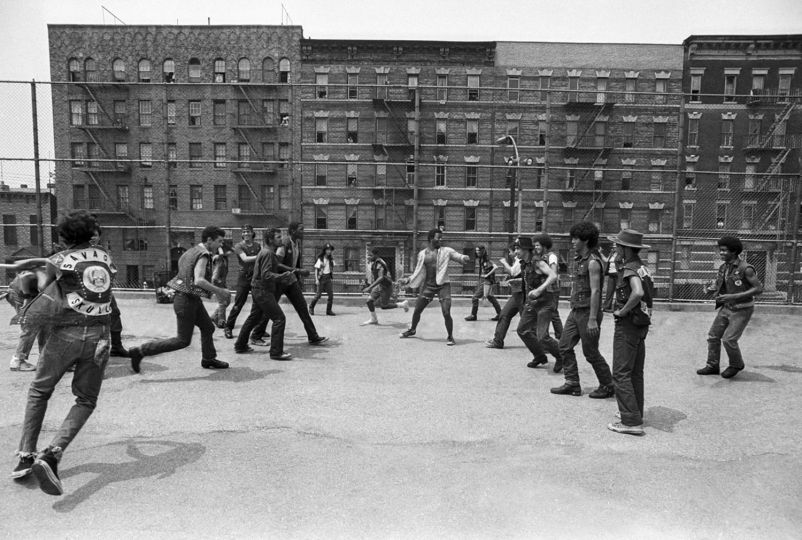

In Anvers, I had a very Catholic education. I was the second of six children. At home, first there was God, then the pope, then my father. My oldest sister became a missionary in Zaire, where she was killed in 1968. After my studies, I left as quickly as possible for Paris, partially to flee. I first worked in fashion. In New York in 1968, I discovered Pop Art. I saw everyday objects in a different way, with more distance, with humor. That significantly affected me. Then I went to London, where, fascinated by the color images of the first television screens, I produced my first successful work, TV Shots, in 1971-72. It was one of the first “reports” on the world, from my room, where I understood distance.

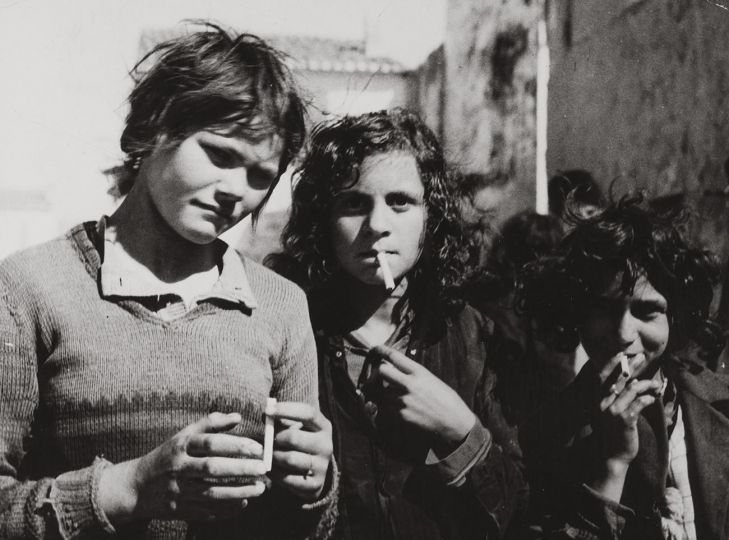

It became possible for me to consider work about Belgium since I no longer lived there. It is difficult to work in the place where you live. We are much less on the lookout. We begin to find everything normal. As a I was making many trips, I often saw that the best images were those that were taken at the beginning of my trip. It was 1973, and I was only working in black an white. Everything seemed gray to me. I often followed the numerous local festivals, carnivals, processions, and other events that were very particular to Belgium and very often the place of spectacular alcoholic excesses. In spite everything, I wanted to avoid sentimental or documentary traps.

It took me about two years to see color that interested me. It was a revelation. I started traveling while photographing in Morocco and India, always in color. But there was Belgium, with this relationship of rejection and attraction. I knew that it was a visually interesting place, where outlandish things happened. It was not for nothing that surrealism was so important there. For me, it was also needed therapy to help rid me of the “Love/Hate” feeling in which I was entangled.

In New York in 1976, I saw the exhibition William Eggleston’s Guide at the MoMA with amazing dye transfer prints, which gave a great sensuousness to color. The discovery of American color photography was essential. I felt a profound affinity to this movement which encouraged me to continue photographing Belgium in color. In Europe, color photography was a rather pictorial aesthetic. We favored the “beautiful” in the classic sense of the term. In Belgium, James Ensor’s paintings had already made magnificent advances towards the grotesque, the sarcastic, and the banal.

My influences mainly stem from cinema and painting. Antonioni’s color work was decisive, in the sense that, despite the artifice of repainted decor, he was able to convey an intense emotion. For me, photography only exists when it takes form in a print, which must be the right expression for what I am seeking. I go over my images many times, as many do, to make a selection and work on prints that I’ve photographed. Thanks to digitalization, color printing has seen a very significant evolution.

We have a lot more control than before. We are much less dependent on limited chemistry, even if there were very beautiful results with the dye. I like the story that we tell about Bonnard. Never completely satisfied with his paintings, he would sometimes go into museums (particularly in Grenoble) where a detail of one of his exhibited canvases was worrying him. An assistant would distract the guard, and he would secretly improve the canvas, armed with a little box packed with two or three tubes of paint and a brush.

In 2000, Editions Delpire published my first book on Belgium, Made in Belgium, with original poems by Hugo Claus. We decided to eliminate the black and white images, which represented the infant stage of my approach.

As is often the case, while recently looking at my Kodachromes, I found many images that I had not chosen at the time but found interesting with hindsight. I also understood that certain black and white images were important because of the mirror effect they establish. Finally, thanks to digital advances, I can rework the ensemble in a richer way.

Belgium was probably the most rapidly Americanized European country after World War II, from which stems the power of this banality, confronted to surrealism and the strength of conserved traditions in spite of everything. Today, it’s much less obvious. Standardization wins with another culture of banality less anchored in traditions. The beautiful, the ugly, the banality of beauty, the banality of ugliness.

These contradictions are also mine.

Harry Gruyaert

Harry Gruyaert is a Belgian photographer living in Paris who is known for his color photography practice. He is a member of the Magnum Photos agency.

Harry Gruyaert, Roots

Republished by Xavier Barral

45€