In this interview with The Eye of Photography, Amanda Smith tells us about her role as Director of Archives at MUUS Collection as well as the handling of Deborah Turbeville’s archives and what we can learn from them.

Could you tell us about your background as well as your role as director of archives at MUUS Collection?

I have a bachelor’s degree in art history and American studies from Rutgers University and a master’s degree in photographic preservation and collections management from Toronto Metropolitan University (formerly Ryerson University). This very specialized program provides an interdisciplinary approach towards understanding the various histories of photography (social, aesthetic, political, technological, material, etc.) and the archival methodologies best suited to collections of photographic materials. I was fortunate enough to be hired as the archivist of The Gordon Parks Foundation during a pivotal period in the organization’s growth and was then promoted to assistant director; in that role I managed the overall preservation of the archive as well as exhibitions, publications and grant-making. I’ve always had a fascination with creating order amid the chaos that often exists in archives, especially those of photographers whose work has been underknown. At MUUS Collection, I can apply that interest and skills to not one, but five entire archives of American photographers who are under-explored. Each archive presents its own unique set of challenges as well as discoveries to be made.

In what state did you find Deborah Turbeville’s archives when her estate was acquired by MUUS. Was she someone who had everything already organised?

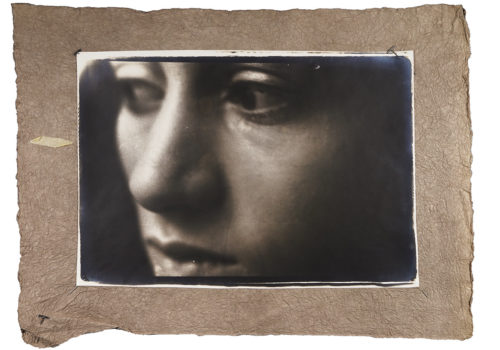

I have found that the state of a photographer’s archive upon their death is a fairly accurate representation of how they approached their photographic practice in life. Like many photographers, Turbeville was a successful commissioned fashion photographer; those materials in her archive were somewhat organized by job with varying levels of description. However, it was Turbeville’s most personal work that offered a glimpse into her personality. Those materials were disorganized, often misidentified and seemingly damaged. As we learned about Turbeville through her friends and colleagues we learned so much though about why this was the case. She was always revisiting images she made throughout her career and repurposing them in new narratives in her collage work. Her last assistant shared that Turbeville enjoyed looking through disorganized images to find work for her collages. She created her own worlds in her work and even built a mythology around her own life. The materials she used to create her work were both incredibly important to her (like seeking out handmade papers from around the world) and entirely not precious; she would not only tear and distress her prints, but she would also walk across them without a second thought.

Apart from her pictures, what is to be found in her archives?

Obviously her archives contain all the photographic materials (prints, collages, negatives, slides, contact sheets, etc.), but also personal papers, correspondence, diaries, workbooks, manuscripts, book dummies, ephemera, film treatments, audiovisual material, equipment, artifacts, books, magazines, and tearsheets. The breadth of the archive continues to amaze us; there is still so much about her work to be discovered.

What has been done so far and what is yet to be done?

The first stage was giving some order to the prints and collages, which we ultimately arranged by series or photo shoot. We have catalogued all of the prints and collages (which have also been photographed) and supportive material. We’ve done an initial preservation assessment of the film material, which we are in the process of rehousing into archival materials. Next comes the digitization of the film material, which will take many years.

Were there many original prints? Are they in good condition? Deborah Turbeville liked to experiment with her pictures, cutting, scratching, taping or pinning them. How do you proceed for the conservation of such works?

There are nearly 9,000 prints made in her lifetime. Because of Turbeville’s artistic practice, assessing condition can be tricky. After spending so much time with the materials, our team has trained their eyes to determine what “damages” are actually intentional. Collection specialists (of any medium) often talk about the difference between conservation and restoration; for Turbeville, we would never seek to correct any of the mechanical degradation, but would only conserve the current state of the work through methods of stabilization. We’ve worked with several conservators to stabilize her collages prior to exhibition to ensure they are safe to travel and be shown.

Was there any important discovery when you first started looking into her archives?

Interspersed throughout the archive were photocollages on identically sized handmade papers, many of which had text paired with images. It wasn’t until we physically pulled them all together that we realized that there were over 130 of them. Each had a numbering system on their verso, so we started to assemble an order. Then, we discovered the original manuscript Passport: Concerning the Disappearance of Alix P when we started processing the non-photographic material in the archive. Finally, we were able to parse the full text and the numbering system and place the collages in their original order. What emerged was the semi-autobiographical photonovella that was never published as Turbeville had intended.

How did you proceed to trace back her life and the trajectory of her work?

Just as Turbeville created fictions in her work, she built a myth around her early life, which had made our initial research difficult. We have been very fortunate to be in touch with so many people that knew and worked with Deborah who have been so generous in sharing their memories and insights and helping us put together her story. Thankfully the notebooks in the archive also offer an understanding of the evolution of her

If you could pick one item — a picture, an object, a document — in her archives what would it be and why?

We have the original storyboards for Turbeville’s first photobook Maquillage. This ‘anti-fashion’ magazine was printed in December 1975—just a few months after Vogue published the infamous bathhouse series—and shown at the Fashion as Fantasy exhibition at Rizzoli. These are so fascinating because they show she was exploring materials, photo processes and collage so early in her career. They combine gelatin silver prints, Polaroids, photo-mechanical processes—all torn and taped in a way that would become signature to her personal work—paired with facsimiles of letters and postcards from women that worked in the fashion industry. It’s also compelling to see how she processed her feelings about her role in the superficial fashion industry through her personal artistic practice. That dichotomy seemed to exist for the next nearly four decades of her life and career until her death in 2013.

More information