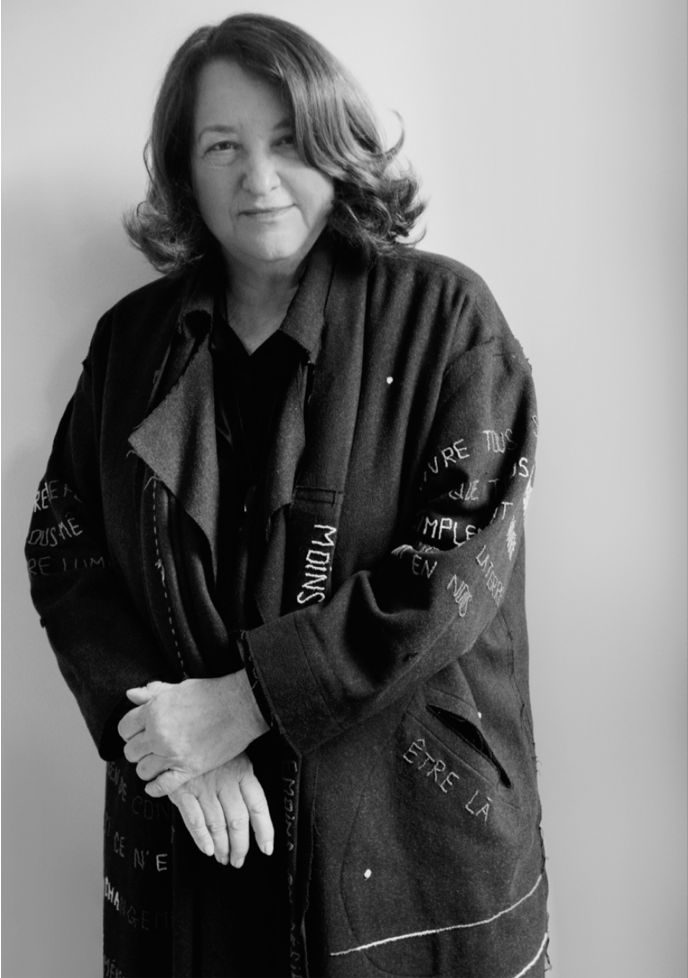

Penny Slinger is a British-born American author and artist based in California. She has worked in different medium, including photography and film and sculpture, and her work has been described as being in the genre of feminist surrealism. Penny Slinger focused on surrealism in the 1960s and the 1970s to “plumb the depths of the feminine psyche and subconscious,” according to a review in ArtDaily magazine. She evokes in this interview her influences and her approach to feminism.

How did you meet Sir Roland Penrose, who became a major support figure in your early career?

Penny Slinger: When I was in my last year of my diploma course at Chelsea College of Art, I was reviewing the history of art to find subject matter for my thesis. I realized I was most interested in art that included the human form, but used it in a symbolic rather than a representational way. When I reviewed the 20th century, I found what I was looking for in the collage books of Max Ernst: ‘Une Semaine de Bonte’ and ‘La Femme 100 Têtes’. In England at the time, Surrealism was not very well represented. However, a friend of mine, Robert Erskine, offered to introduce me to Sir Roland Penrose. He said Roland was the only person he knew, in England, that really understood Surrealism. After the introduction was made, Roland was incredibly generous with his time, knowledge, and enthusiasm. It was Roland who introduced me to Max Ernst in Paris and got my student work into the exhibit ‘Young and Fantastic’ at the ICA, London, in the summer of 1969, just after I graduated.

Where do you see yourself fitting within the context of the British Surrealist Movement? How did you see women interface with the movement in general?

I was never part of the movement as such because the heyday of the Surrealists was over by the time I appeared on the scene. This saddened me a little as I was longing to be part of something bigger than myself and I wanted the co-creative dynamic of an actual movement. However, I felt the tools offered by Surrealism had long-term validity and application.

I was always more attracted to the European Surrealists than the English. As far as women Surrealists were concerned, I did not feel that the women working within the movement made art that delved into areas specific to the feminine, and that is where I felt my contribution came into focus.

In retrospect (because I was not that familiar with her work at the time) I feel more akin to Frida Kahlo than any other female artist. She used the language of Surrealism for her own form of intense introspection and self-reflection. From the start, I wanted to apply the techniques opened up by Surrealism to probe and lay bare the female psyche. Similar to Frida, I was not so involved with fantasy, but with plumbing the depths of the subconscious in order to mine the jewels of the inner being and shine some light on them.

How did the topics of sex & religion become of interest to you?

I think these are of deep interest to the seeker of truth and anyone with a physical body! But maybe that’s just because of who I am; my particular astrology, and make up…

Sex held a fascination for me from an early age. The first portraits I did of my parents when I was 4 ½ years old did not fail to include their sexual organs!

Growing up in England in the 1950s was certainly not a sex positive climate for women. The general consensus was that sex was something a woman had to submit to for the pleasure of man. This did not seem good enough for me. I felt there had to be more to it than that. Therefore, I embarked on my own campaign to find out, using my body and mind as the set crucible, what was really going on. Then I sought to convey my findings in my art, complete with all the contradictory signals surrounding the subject.

Religion was another sacred cow whose divinity I questioned because of the way I saw it practiced, as well as the restriction and dogma associated with it. So, I soon rejected and renounced religion, but was always passionately spiritual. I discovered the path of Tantra later in life, which resolved the dichotomy for me because it included sacred sexuality.

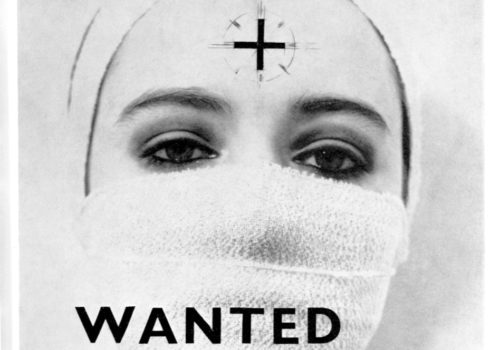

In one of your collages for ‘50% – The Visible Woman’, you have a portrait of a woman with “wanted” in text over her mouth. Why was this phrase important for you?

The woman is a photograph of myself. I chose to use my own image in my work, early on in my career. I saw that women were central to subject matter throughout the history of art. Generally, the woman was viewed through the eyes of a man. I wanted to be viewed through my own eyes and be my own muse. Also, I felt that I could take the most liberties in transforming my own image rather than doing that to someone else’s.

I used the ‘Wanted’ slogan as a double entendre. The main association was with ‘Wanted’ posters of outlaws. I put myself in that position, outside the law. I was also aware of my allure as an attractive young woman, so that was the other side of the reference. The bandage over the mouth suggested the covered face of a bandit, and also represented the idea that I was being gagged because society sought to stop the things coming out of my mouth and wanted to silence me; to silence the outspoken feminine.

Themes of vulnerability, and also strength, are apparent in your self-portraits. Has balancing those two notoriously been a struggle for you?

It is the struggle flesh is heir to. Particularly female flesh! Aren’t we all a paradoxical mix of these qualities? I always felt women needed to claim their right to equality not by being more like men, but by being fully themselves. The feminine qualities of being have been undermined for so long. It is time for them to assume pride of place for the attributes that are theirs rather than trying to match up and conform to some masculine standard. It’s in the ‘frisson’ between vulnerability and strength that rich and fertile arenas can be found.

How do you incorporate ritual into your artwork?

Creating art is a ritual in itself. It takes many complexions, depending on the requirements of the project. One of the most interesting experiments I conducted in art and ritual was in the creation of the 64 Dakini Oracle. For that project, I worked with more than 50 different women. Each would go through a process of transformation, in their consciousness and through the use of costuming, makeup, body paint, and props. Once prepared, we would go into my video studio and ritualistically invoke and evoke the spiritual entity, the Dakini (manifestation of a specific Feminine Wisdom). The energy of this being would be felt palpably and then I would make a photographic and videographic record of how the transmission manifested. Art and ritual are natural companions. In tribal culture, they are intimately interwoven. I appreciate the meaning and life this brings to art, imbuing it with vibrant totemic qualities. I seek to make all my art totems of experience.

You have mentioned honoring “the divine feminine” within your work, but also have spoken in interviews about honoring the balance of masculine & feminine within you. How does gender identity, & the rise of non-binary identities influence your work today?

I have always felt that the gender specific boxes we are placed in stifle us. We all have male and female elements within us and their dance is the dance of creation. Inspiration is the lovemaking of our male and female inner energies. Experiencing the divine feminine is not the birthright of women alone. She needs to awaken in the hearts of everyone. The feminine needs to be supported to rise because she has been suppressed for so long. However not to create a matriarchy. We don’t need that anymore than we needed patriarchy. We need balance and flow, each supporting the other in each other and in ourselves. That’s the new harmonic. It’s much more androgynous than the way affairs have been handled for a long time. But this does not mean a flattening out of the male-female dynamic. That’s where the juice is. In Tantra, the aim is union from duality, but if there was no duality, the coming together wouldn’t be nearly much fun! Perhaps we could have removable sexual organs that could be exchanged. That would spice it up and remove all this boring gender role nonsense.

In the context of the third (and transitioning into the fourth) wave of feminism, do you think your work has changed? Do you find that people receive it differently?

It is interesting, as the arch of feminism appears to have now come more in alignment with the views I held from the start. My difference with the face of feminism in the ’60s and ’70s was that in seeking equality, it seemed to take on more masculine characteristics to deny the truth of the body and the emotions. Going to a couple of those political meetings back in a day, I felt only my head was being addressed, so it may as well have been cut off!

The new waves of feminism are much more body and sex positive. They are holistic, and even include spiritual qualities. The more militant politics of the past denied women their sensual sides. But this has to be part of the new knowing and I am glad to see feminism coming of age in this way.

My work evolved according to my own understanding of the nature of self and its liberation. At first, it was more psychological and introspective, then broadened into a more expansive view of self-nature.

The art world is still only embracing my early work. I hope in time, the breadth of my journey on life and art will come into the full light of day and the trail I have emblazoned be recognized. Nevertheless, I have to follow where I am guided, regardless of how it is seen by others at the time.

I recently completed a new series entitled ‘Reclaiming Scarlet’ which integrates my own perceptions with fashioning an archetype of the ‘new woman’. It reflects on what I see happening in current women’s movements such as the Red Tent movement around honoring the moon cycles.

If you could give any advice to young women artists today, what would you tell them?

Look for a pure source of inspiration, uncluttered by anyone else’s opinions, likes or dislikes. Anything that conforms to the views of others can only be more of the same and never break new ground. You can immerse yourself in the milieu of art and culture, for everything arises out of a context and that is what gives it roots and relevance. But then cut your own trail. Go where others have not dared, for in the wilderness is where you will encounter the rawness of who you really are. That is your raw material, the mud from which your lotus can grow. Wallow in it as fertilizer for the soul. Do not be afraid to be a dirty girl, for every work of art is a Virgin birth.

This interview was published in the issue 16 of Musée Magazine that came out in October 2016 and is available for $65.