We can see very diverse narratives in Sofia Tatarinova‘s series of photographs created during a trip to Udmurtia with other Rodchenko School students: expanses of forest, snow sculptures, portraits with ladies of a Balzacian age, texts with the stories told by our heroines. At first sight the four groups of subject matter in the series represent the classic step-by-step ‘disclosure of theme in a literary composition’: portrait – inner world of the hero (heroine) – background – commentary. The lonely women of a remote Russian province.

Let us begin with a criticism and immediately put a spoke in the wheel of socio-culturalism, that minor demon of our age. There is something very dubious in the phrase ‘cultural trip’, although the trend has become international. The French travel to Tunis and Oceania, the Americans visit Mexico and Georgia, while Russians travel across Russia – as far as they can go. But why should creative ability be stimulated by a change of location? After all, we don’t send student violinists to Udmurtia to make them play with more expression, or ballet students to make them leap higher, or young mathematicians so they can solve problems better. Why do artists (or photographers in this case, who aim for such status) have to take these journeys? What’s more, to places where most would never venture in their right mind, in other circumstances. The answer lies in an urge felt by teachers at leading Moscow schools of photography to instil a sense of responsibility and a critical view of the reality of life in the younger generation.

In the Soviet past artists always drank during trips for creative work-experience, and earned money (by crafting idols of the revolutionary leaders). On such expeditions Dmitry Prigov saw in the windows of provincial shops figures of swan geese made of lard, moulded by the assistants in their leisure time. He jokingly contrasted the lardaceous swans created ‘for pleasure’ to his own soulless bronze statues commissioned by the state.

Considering this strange coincidence between naïve sculptures made of lard (thirty years ago) and snow (today), we should interrupt our critical zeal and take a closer look at what the work of Sofia Tatarinova represents. And in what rank the snow kings and queens are presented here – mushrooms, bears, Father Frosts…

To begin with, the social commentary imposed on us by the form of ‘student practical experience’. Udmurtia is a very remote place, despite its relative proximity to the capital (closer than Vladivostok, for instance), the furry heart of Russia where lonely women (most of them widows) languish, devoting themselves to amateur artistic pursuits (not embroidery or singing, but snow sculptures). What an original display of female resilience and creativity, despite their living conditions in that far-off land…

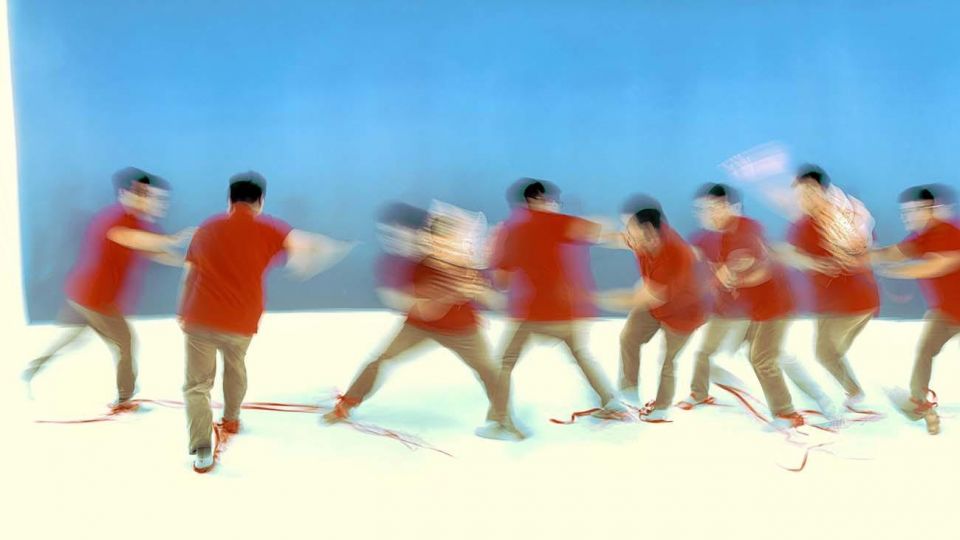

But in an different interpretation of gender and its consequences, Sofia Tatarinova’s work would not include this quantity of snow statues, and the extended morphological suite of articles crafted in snow ‘freezes’ social zeal, reducing it to formal ethnographic curiosity, as described by Prigov.

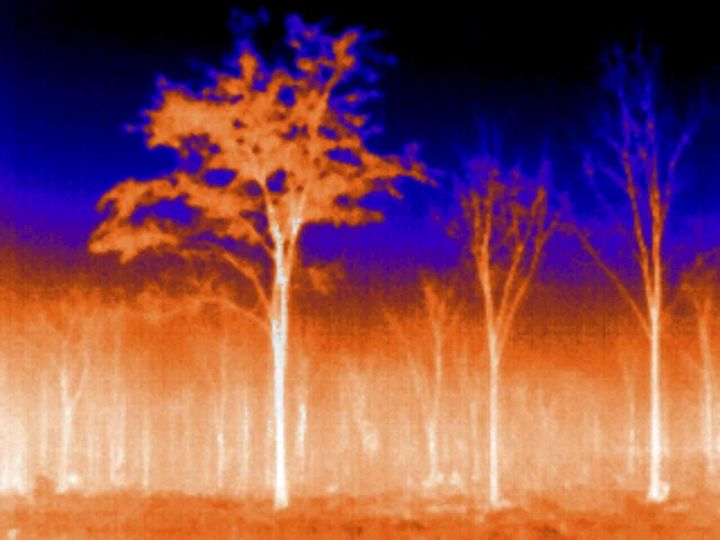

However, the ethnographic (conceptual) approach also turns out to be not entirely relevant when we turn to the third component of her project – landscape views that could be taken from chocolate box lids or New Year greetings cards. The ‘glossy’ character the author presents to us is completely intentional, apparently genetically akin not to digital manipulation of the image, but to the ancient skill of retouching with a brush or pen, again, from the Seventies: ‘here the boughs of the fir trees tremble in the wind, here the birds trill with alarm’. Fairy-tale beasts are given a mythological land in which to dwell.

But an antagonist can also be found to the kitsch ‘mythological’ component of the project – this is the texts the artist offers as a document, as evidence of authentic speech. They are all undoubtedly tragic, telling how the women’s husbands committed suicide, but this is the epicentre of the tragedy, drifting and barely perceptible. The husband died after visiting a fortune-teller? Why did he go to see her? Or is this the interpretation of a jealous woman? How did he die? By hanging? No, was it the husband of another woman that hanged himself? The borderlines of mythological discourse are washed away, it overflows into everyday life and subversiveness.

In her Udmurtian series Tatarinova follows the path of trangression, when every subsequent part is undoubtedly ‘external’ in relation to the preceding statements. And this blurring, fluctuation, in the end turns back on the photograph itself, giving the latter the characteristics of an artistic transgender, exploding from the positivist clichés and social engagement imposed upon it. Paradoxical, frightening and at the same time ironical, Sofia Tatarinova’s work occupies an external position in relation to the present speculative political mainstream, and that is splendid.

Evgenia Kikodze

EXHIBITION

Udmurtia

by Sofia Tatarinova

From March 25 till May 4, 2014

Zurab Tsereteli Art Gallery

Prechistenka, 21

Moscow

Russia