At the origin of this feature, the email of a reader, Marie-Christine Bouillé:

Why don’t you mention Touhami Ennadre‘s exhibition, Qasida Noire, at the Mohamed VI modern and contemporary art museum in Rabat? Yet you know this singular work – an in-depth quest for the resources of photography and its original black and white – presented here on a special paper, made for him in Japan and from which Touhami chose the tree from which it is made; without forgetting that he prints himself each of his large formats, therefore, each are a unique piece.

A discovery that your readers deserve, right?

Marie-Christine Bouillé

We did not know this photographer so we offered her to do the interview. Here it is :

Marie-Christine Bouillé: Touhami Ennadre, when you say that Qasida Noire is the exhibition of your life, what do you mean by that?

Touhami Ennadre: What I did for this exhibition at the M.N.MVI, never again, I will not be able to do it again either in itself or elsewhere. I went to the end of my strength. We gave, my team and I, the best of ourselves. Despite the multiplication of circumstantial problems and pitfalls on my way, I felt on a mission from start to finish and I did not give up. You must know that for a very long time I wanted to show my work in this way but, in Paris, it was impossible.

MCB: Why?

TE: Because in Paris, decision-makers have very fixed ideas about what photography is and I don’t tick any of their boxes. You also have to belong to a network and I have always avoided that. Like the labels African, Arab or Moroccan photographers. I find cultural ghettoization dangerous because it turns artists into pawns. I always thought it was fabricated by neocolonialists and pursued by white niggers for the sole purpose of racketeering pigeons and institutions. There is nothing natural there, everything is flawed.

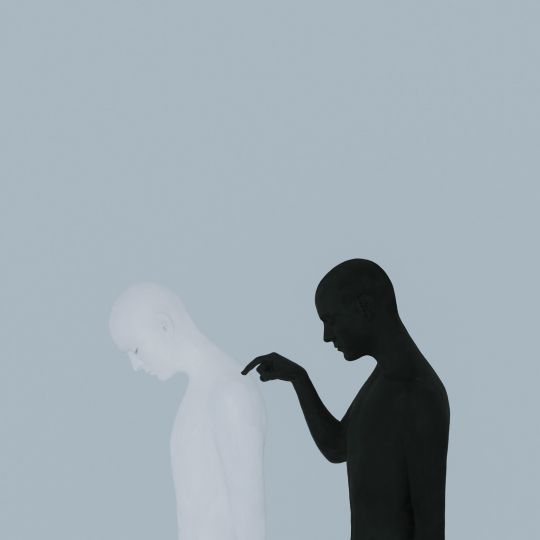

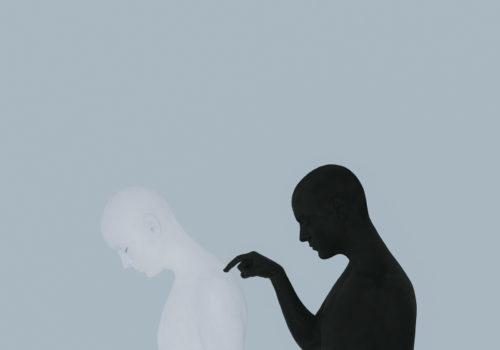

Here, at the M.N.M.VI, thanks to the generosity of His Majesty, I was able to create Qasida Noire whose aesthetic uniqueness and scenography make it unique. I don’t think there has ever been, in the history of photography, such a demand for a dialogue between its content and space: QASIDA NOIRE is made up of three spherical circles, immersed in black-light, which impel the three movements. The first circle presents the essence of my work on the prayers of men, on what connects them, that is to say the Faith. The second is meeting my family, on a journey to the depths of my country. The third penetrates to the heart of my artistic approach. It is very unique and it takes place in Rabat. Nowhere else, in New York, Paris, London or Berlin, has such a device been offered.

MCB: You have chosen to produce it – a particularity of your exhibitions since you shape yourself, in your studio, the printing of your works, which makes each one a unique piece, exclusive to the event – on site, in Morocco, while you live and work in Paris: why?

TE: By this choice, I wanted to prove that Moroccans are not the imitators that are too often described and that it was possible to initiate an extraordinary exhibition in the country of my childhood. If I had stayed in Paris, of course, I would have avoided many administrative and practical complications, but I would have deprived Qasida Noire, which is a tribute to my people dedicated to the world, of a key dimension: its roots in my native land.

As for the production that differentiates my work from that of other photographers, the reason is simple and fundamental: for me, photography is a total act. No question of being replaced by a laboratory technician, I pitch in from the shooting to the structuring of the space necessary for the eyes of others to complete what I received by pure chance: my photography.

MCB: Still on this dimension of total act, tell us about the paper used for the prints of QASIDA NOIRE. You would have chosen even the essence of the tree from which it comes?

TE: For a long time, I was looking to work on an artisanal paper close to human skin or parchment. I ended up finding a family factory in Japan that took up the challenge. During my trials with these people, their thoughtfulness, their determination to succeed with me, overwhelmed me. It was the first time they had worked on handmade natural paper to find the deep black I wanted to achieve: I had presented them with a problem that they could not fail to solve. And they sacrificed the unfortunate five days of vacation they had in the year. What is great with the Japanese is that they are always ready to learn, to improve… In the end, we got what I wanted, these people learned from my approach and I learned with them.

MCB: The realization of QASIDA NOIRE required a year of work, you present seventy works of the very large format that you prefer in a scenography designed with the Nigerian-American architect Anna Abengowe: beyond the feat, what is the challenge of this monumental exhibition?

TE: The same as with each print: surpassing myself without any calculation. This is what guides my approach: to always go further, beyond the mastery of my art and my profession, to access, with fear in my stomach, the unknown, the incredible. The magic of a work can only come from this vertigo and from a collaboration without the knowledge of the other. Hence my admiration for ‘masters’ like, in painting, Tintoretto, Velasquez, Goya, Caravaggio, Delacroix, Monet, Pissarro, Cézanne and so many others… In the cinema, there are indeed Murnau, Dreyer, Lang, Hitchcock , Tarkovski, but I’m so obsessed with Japanese aesthetics that I spent my time watching again and again films by Ozu, Mizoguchi, Kurosawa to name a few, in arthouses or at the cinematheque. I was also blown away by Ukiyo-é, the masters of printmaking like Hiroshige, Hokusai, Harunobu, Utamaro, in photography, by the Shiseido brothers, Shinzo Fukuhara and Roso Fukuhara. My answers to the question of the role of shadow and light, I found them in poets, writers, painters, Japanese masters of cinema, more than in photographers who confront us without reason with contrasting representation or the abuse of the wide angle. The real light that gives value to things in life without reproducing them, that knows how to make the shadows speak, is the very light that makes your style.

MCB: In addition to your declaration of love to the Moroccans after having traveled the world, especially to the little people of your medina and other unknown places in your country, what other message have you instructed QASIDA NOIRE to convey to whoever discovers it?

TE: Hope. Remind him that light comes from black, that black is light. That one can come from the darkest alleys of the medina or from a slum and, through hard work, live from one’s passion.

MCB: Precisely, Touhami Ennadre, let’s go back to the beginning: how did you become a photographer?

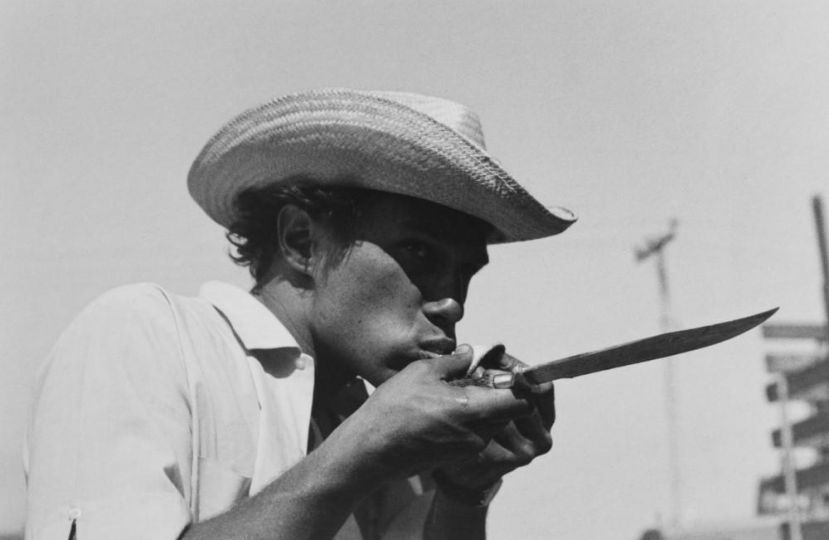

TE: It is impossible for me to talk about my career as a photographer without mentioning my life, as the two are linked. I was trained in my native alley in the medina long before my mother gave me my first device. It was there that I learned to anticipate, to watch, to escape the ‘m’quaddems’ and the port cops. This allowed me, later, in New York, to take pictures in the subway or at Ground Zero in the face of the cops despite the bans imposed by Giuliani. I am grateful to my street for having made me who I am.

I grew up in a slum in the Parisian suburbs, in La Courneuve. There too, it was hell and our future, was sport, comic or criminal. My mother gave me a camera shortly before she died. I had just given up my passion at the time, football, from which post-Six Day War racism had turned me away. I was idle and she feared that I would turn out badly. So she saved for months, penny by penny, to buy it.

MCB: Did your mother foresee that photography could become a profession for you?

TE: No. Her only obsession was to protect me. My mother gave it to me to give meaning to my life. She gave birth to me twice. And it is hard to forget as aesthetically too, I learned everything from her.

In Casablanca, my mother was weaving rugs. Since there was no electricity or roof at home, at night I would hold a candle for her so she could work. I grew up in the color of the carpets and in the dark of the night with, above us, a sky filled with stars which shone. I remember as a child, I took them for human beings. I was very scared because I thought something terrible was going to happen to us. Years later, I found, in my way of shooting photos, of illuminating the dark, everything I owed to those long evenings spent lighting up my mother. They were my school.

MCB: When would you set your transformation into a ‘photographer’?

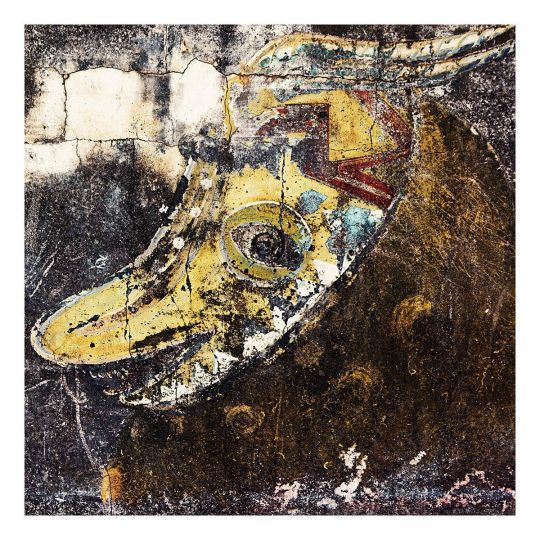

TE: I started in the street in 1974. In 1976, my first photos won me a critics prize at the Rencontres internationales de la photographie in Arles. After a while, it became very easy for me to take pictures on the sly, unbeknownst to others like a pickpocket, but I soon had a problem with that. All right, I’ll go to India, Africa or elsewhere, photograph the misery of others, then I’ll come back to France to promote my work in search of possible success… And after? I kept asking myself: who is photographing who? Me, clinging to my camera, or my subject? Did having a camera give me the right to intrude into other people’s lives and then claim to be a hero of photography? And then, at a certain moment, I understood that photographing had to be a close combat; that I had to get as close as possible to others to express [gesture of squeezing] the essential in them.

MCB: When would you place that moment?

TE: During my mother’s funeral. I was in this cemetery, my camera glued to me as always, without feeling the right to machine-gun grief. It was thanks to the hands of my family, who were screaming their pain, that I understood: photography is not in the documentary but in the imagination, however contradictory it may seem. I had to dribble reality. From that day on, photographing was no longer a pursuit of visible reality but its erasure in order to let the imagination reveal the real.

MCB: How does this change the very act of photographing?

TE: In all. After that cursed day, as the idea of rediscovering the brightness of her woolen threads never left me, I tried my hand at color photography. To give it up very quickly, too artificial and narrative for me. In fact, my mother’s funeral buried me forever. To illuminate this drama, I saw that I needed a certain black and this is how this luminosity imposed itself. In this sense, I feel close to the pioneers of photography.

MCB: Your camera does not have a viewfinder, why?

TE: It is my approach that imposes it. In this way, there is no intermediary between the subject and me. From the start, I understood that photography was like human relationships: the more open we are, the closer we are, the better we understand the other and the more we learn from him/her. I work with a wide angle but not like in classic photography where, there, it is used rather to distort. No, I use the wide angle to form the photo. So I have to train every day to look with the same discipline as an acrobat or a gymnast.

MCB: If I understand correctly, your device is an extension of yourself…

TE: That’s right. When I photograph, my camera and my eyes are the only parts of my body that act, well [Smile]… with my legs because I have to be reactive. I turn off everything else.

MCB: You say that photography is learned in the street, by going out in front of others, you have traveled the planet and often chosen to photograph places that are not recommended, people who are poorly looked at, why?

TE: In my work, there is no representation, there is only a cry. There has to be an interpenetration with the other, that’s how I see photography. Make this cry heard, let it be known that what happened is inhuman or extraordinary, make it visible, audible and universal.

MCB: What do you do with the risks you take?

TE: I’m always scared because I photograph very closely, almost glued to the face of the other. I have to be as quick as I am careful, I play my skin but fear teaches you to be fair and precise. For my series on trance, I went to Bahia, Recife, in the favelas of Rio, in places that do not forgive anything. In Bombay, Port-au-Prince, Addis Ababa, in the Bronx, the night is terrifying. For example, in the New York subway, I was as afraid of the cops as of the gangs… Generally speaking, when a photograph appears, it confuses you and hits you in the heart after having waited for months , sometimes you have to act very quickly before it disappears.

MCB: You were in New York on September 11, 2001. You went to what became Ground Zero, why?

TE: When I became aware of the tragedy, I said to myself that I had to act, but all I knew was photography. So I rushed to the spot. I have never been so scared in my life, no authorization, a terrorist face, but it is with this fear in my stomach, my anger and the indignation in my heart, that I worked. It was a beautiful morning, remember. To see the sun go black, to smell that smell, it was poignant. An indescribable moment that I felt the obligation to witness. As usual, I approached people as much as possible, but there I had a problem: how to bring out this drama without identifying it, without situating it? It was universal and a monstrosity, wherever it came from, was unacceptable. I wanted to identify what was behind the visible. On September 11, the whole world was affected. That’s why you never see New York in this work. Only the burden of pain and the poetics of the drama remain. I accept the confrontation with the horror of violence but not the spectacle it produces.

MCB: Your works are part of the most prestigious public or private collections, you are recognized. Looking back, what do you think of this success?

TE: I come from the darkest alley in the whole medina and I am present in a museum in New York! It means that my alley gave me a strength capable of breaking down walls but also, sorry to repeat it, that with hard work, we can get there. This is what I would like to pass on to the kids in my neighborhood.

MC: Where did your Maison de la Photographie project come from, a school and a place of exchange open to the world and to other artistic expressions, in the very street of your birth in Casablanca?

TE: Many young artists asked to learn from me. So I told myself that I would bring them to the medina to give young people from the neighborhood the chance to meet others. As I have forty years of archives that I intended for my city, it would form a whole: the Maison de la Photographie. I spotted a piece of land, found a Japanese architect, Tadao Ando, whose approach was similar to mine, designed the building and its programming with him, worked on this project for twenty years, unfortunately, suspended for the moment even if a synonymous work rises slowly in the same place.

Rabat, November 16, 2022

Qasida Noire is presented until January 30, 2023 at the Mohammed VI Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art.

Museum open daily from 10 a.m. to 6 p.m., closed on Tuesdays and public holidays.

Corner avenue Moulay El Hassan/avenue Allal Ben Abdellah

10 00 Rabat, Morocco

http://www.museemohammed6.ma/

[email protected]

Facebook : https://web.facebook.com/touhami.ennadre

Instagram : https://www.instagram.com/touhamiennadre/

Twitter : https://twitter.com/TEnnadre