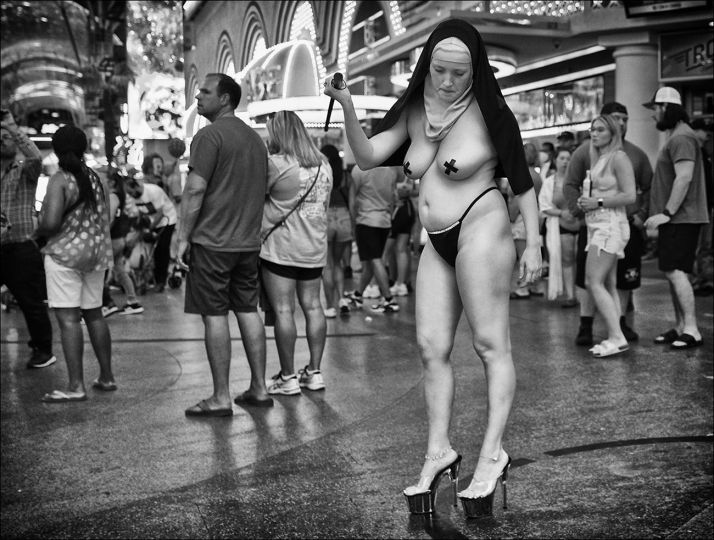

All the world is a stage, theater in the round, and when we walk upon it, we take action accordingly. We become actors in the movie of our lives, taking on a public persona that is in part crafted by the landscape itself. The milieu becomes a defining factor in our lives, but the more integrated we become with it the less likely we understand its affect on our identities. As a native New Yorker, I belong nowhere else. Too much of the spirit of this city has consumed my flesh. I love and hate it all in a single breath, but never would I leave, or at least—not yet.

Thus, any book on New York instinctively attracts me for any book on New York is like looking at pictures of me, my family, my friends, even if I’ve never seen that sight before, even if that picture was taken before I was born. Two new books on New York explore the landscape; more specifically each of them explores the façade of street-level businesses, of the means by which we communicate our needs in a symbiotic relationship that reaches the highs and lows of the urbane vernacular of American capitalist landscape.

Laundromat by the Snorri Bros. (powerHouse Books) is a compendium of storefronts that go overlooked, so integrated are they into the American landscape that most do not think of them at all. Yet for Snorri Sturlson, the laundromat was an unfamiliar place, for he came to NY from Reykjavik, Iceland, a place where laundromats didn’t exist.

That laundromats could be exotic to the foreign eye is a testament to the ability by which we adapt to out surroundings, and hold to the belief that the conventions of modern life are proof of our progress. Having lived in New York since 2001, Sturlson is both insider and outsider, able to look at the American environs with fresh eyes and make us look at it anew. In Laundromat, the Snorri Bros. present 187 photographs of facades, in luminous full page prints, so that we can begin to see the beautiful variations on a theme that make each one an integral part of the New York landscape.

As D. Foy writes in the book’s afterword, “It was, Sturlson said, as if everything he’d gathered about America over the years—the loneliness and pathos of the Jim Jarmusch films he’d seen growing up in Reykjavik, the mysterious lack that pervades the prose of Paul Auster; the shade of Weltschmertz in the songs of Tom Waits, and the city’s ambivalent sense of gritty despair and taunting possibility that have drawn so many millions to it—all these contracted in a brilliant epiphany. There were literally thousands of laundromats in NYC. A few photos would have been too many, but hundreds hardly enough. The collection, Sturlson saw, would be a portrait in montage even as it constituted a history, an anthropology, a sociology, an imagistic commentary on the economics and politics of America itself.”

The book is organized by borough, taking us on an All City tour, and in that way we can contextualize this experience as that which is shared in some manner by the city’s citizens, one and all. There is a great sense of the populist spirit to these photographs, of a tribute to the honor of the common woman and man.

Compare this approach to that of James and Karla Murray, whose new book New York Nights (Gingko Press) is the nighttime companion to their previous book Store Front: The Disappearing Face of New York. Here the Murrays give us a guided tour of some of New York’s most famous nightspots, places that have become synonymous with the city that never sleeps. Organized by borough, with a focus on Manhattan, New York Nights presents a portrait of the venue at night and a history of the place.

In these photographs, we are drawn to the signage, the way it glows in the dark, and becomes emblematic of the establishment. We may be reminded of Tom Wolfe’s essay on Las Vegas, of the idea that the American vernacular is one of capitalist design, of the way in which signage becomes an art historical trope as well as a form of public discourse. We may consider the histories of these venues, and the way in which they have become both emblematic of their era as well as part of the larger American iconography, or we may simply be overwhelmed, overcome, entranced by the glow of light and color and the way it captivates the eye in both two and three dimensions.

The beauty of New York is that the streets are pure democracy, that we cross paths with all kinds of people as we set out towards our destination. This democratic spirit is reflected in the images presented here, be it the Cuhchifritos Frituras up on East 116 Street and Third Avenue that offers mofongo al pilon and jugos tropicales, or the 21 Club that has a line of lawn jockeys set up welcomingly on the façade of the former speakeasy turned high profile restaurant.

Taken together, Laundromat and New York Nights show us a New York that is so familiar that the photograph makes us stop and consider that which we take for granted and how it informs our understanding of our lives. Both books share a love for the landscape of the street and the way in which we interact through the use of signage, architecture, and facades to handle our daily affairs. Each book reminds us not to take for granted that what we share, with each other and with the world, as we go about our lives. It reminds us that the street is where we cross paths, and it is the storefronts on these streets that offer a very distinct and powerful experience.

Miss Rosen