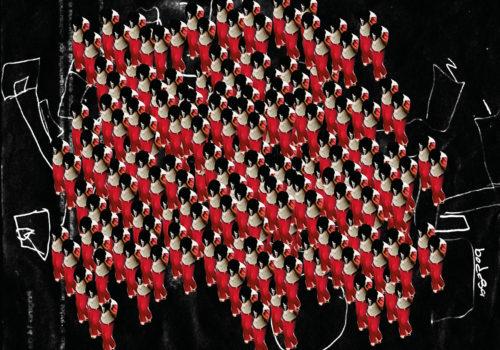

The urban landscape is more than buildings and roads; it is a series of signs, murals, and iconography that helps to define the place. Signs provide direction, giving us a frame of reference, a means to engage with opportunities that only exist in the space between us. Signs are stories on display, creating a mood with the combination of image and text that capture the imagination. Signs are an invitation, visual engagement, and if we do decide, an opportunity to participate in their offer. Signs are the lure. To buy into the sign, or not to opt out, that is the question of our times.

Sign Painters by Faythe Levine and Sam Macon (Princeton Architectural Press) is a gloriously told history of the contemporary art of sign painting. This book pays homage to the traditional form of the craft, of a methodology that precludes the use of digital technology. The artists featured here are those who adhere to the time-honored methods of hand painted signs, with a wide array of photographs that give us a private tour inside the artists’ studios where they manifest works of heart and mind. From these studios come finished works that we have only seen in situ, where it takes on a larger meaning by becoming a part of the landscape itself.