“Advertising is, after all, artificial truth,” writes Steven Heller in the introduction to Advertising From the Mad Men Era: The Sixties (Taschen). This is the second in a two-volume slipcased look at the mid-century edited by Jim Heimann and featuring texts by Steven Heller. The first book, which covers the Fifties, introduces us to the classic lexicon of myths and symbols of the American advertising industry. As Heller aptly surmises, “Fabrications and exaggerations existed, but no one cared because the images, words, and concepts toed the line between the possible and the preposterous. What’s more, by the early Sixties postwar Americans were happily conditioned to believe anything the mass media put forth, and advertising was embraced without question. Consequently, many magazine ads and TV commercials were viewed more as entertainment—or pastimes—than as crass sales pitches.”

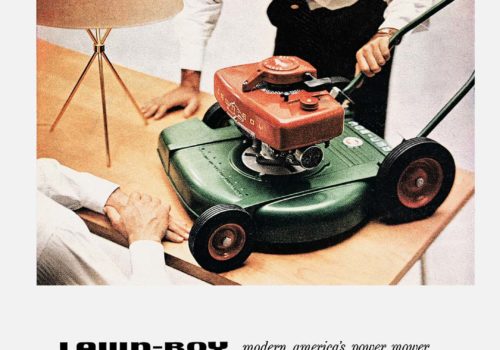

The 1950s and 1960s redefined the space where the public and private met in American life by creating a form of communication that enabled the consumer to both actively and passively participate in the conversation about keeping up with the Jones. The photograph is essential to this conversation for it offers an Ideal that appears as the Perfect American. Of course, who defines this Ideal is predicated upon the power structure and postwar America was nothing if not a bubble. It was in this bubble that modern-day advertising was born, forcing the Haves to hold on for dear life while not-so-subtly showing the Have Nots they do not exist at all, unless, of course, they are willing to assimilate and take on the heavily codified rules while simultaneously not making waves.

This is advertising’s greatest success: the viewer is made complicit in the advertisement itself. There is a subtle wink between advertiser and consumer, the shared but unspoken message of cultural assimilation. What makes these volumes remarkable is the way in which they are at one eerily familiar in today’s world. While the advertising industry must remain on the cutting edge, forever advancing the conversation about keeping up with the Jones or Kardashians or whoever is trending on Twitter at this moment, the underlying message has not changed one bit. If you want to be validated by legitimate society, we strongly suggest you buy this.

What makes advertising so insidious is the way in which they craft the conversation to appeal to our vulnerabilities, desires, and fears. Advertising from the Mad Man Era purports to make you one of us provided you play the role you are given and spend that hard-earned paycheck on these services and goods. The photograph is the primary vehicle for this conversation, for in these two volumes there is nary an ad that relies on words only. It is first and foremost the image that draws us in.

As Bill Bernbach, one of the doyens of the industry, aptly observed, “It’s not just what you say that stirs people. It’s the way that you say it.” And this is where the photograph comes in to play for the message of advertising is strongly rooted in the non-verbal cues of the photograph. Before the word hits, there is the image, the person or thing or place that is pictured in its most flattering light, a positioning of it to create intimacy and grandeur at the same time. Because the advertisement will not work if it does not create aspiration in its audience. The want has to be so great that we will stop to read the words; which is to say, the photograph has to be so compelling that we unconsciously stop everything we are doing to engage with it.

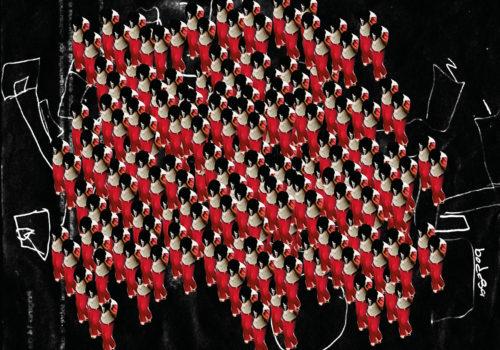

Once engaged, we are being pitched, being told, being sold, being seduced, being promised a whole bag of tricks. What makes these two volumes fascinating is the way advertising has become a cultural history unto itself, offering up a blatantly (racial, sexual, gender, socioeconomic) biased look at how America wishes to see itself. The success of an ad is determined by both its ability to sell product as well as its ability to brand, that more ephemeral and nebulous quality of creating a reputation based on both performance and promise of a better life. And in this way, Marshall McLuhan had it right, “Advertising is the cave art of the twentieth century.” Because it combines magical thinking and iconography with the cold hard reality that cash is the driving force in our society.

As these two volumes brilliantly illustrate, the American Dream is aspirational, and predicated upon the capitalist-Calvinist doctrine that gave birth to the Protestant Work Ethic, God rewards those who pull themselves up by their bootstraps by giving them the opportunity to spend every last dollar on things they believe they need will make them: happy, attractive, successful, etc. Advertising takes this idea as far as it can go by creating iconography that reinforces the belief that what we need to be complete is within our grasp, at the very least it is afforded by the complex layering of meaning found in the enjoyment of advertising as a form of identity and entertainment.

And yet, not at all ironically, Advertising from the Mad Man Era is an absolute delight. Like many Taschen volumes it is lavishly oversized, filled with hundreds of pages and images beautifully reproduced and contextualized with Heller’s brilliantly crafted essays. The pleasure of paging through these volumes is heightened by the dialogue between the two books as they cover twenty years of American culture during a time of transition from the world we once knew into the world we are becoming today. What makes this book slightly shocking is the way the advertisements truly draw you into their realm, and despite the benefit of intellectual hindsight, they remain a true and strangely lasting pleasure for the senses.

Miss Rosen