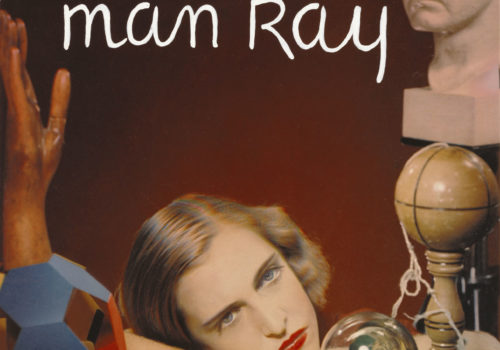

At the age of 30, Man Ray entered Paris. It was 1921. He stayed until 1940. Though he considered himself first a painter, it is his photography that has produced the most iconic images of his career. Many of those images are featured in May Ran in Paris by Erin C. Garcia (J. Paul Getty Museum), a beautifully produced collection of the artist’s experiments in the medium.

Man Ray entered into the Dada dialogues. His fluidity in the forms of photography produced distinctive results. Most notably, his Rayographs, objects placed on photographic paper and exposed to light, recalls Marcel Duchamp’s “readymates”, playfully relating to the two dimensional image as something between an assemblage and a light painting. Fertile ground for a mind as inspired as his own.

Twelve of the Rayographs were published in Les Champs délicieux, a portfolio created from one-of-a-kind prints created individually by Man Ray. Here he moves into the form using depth, texture, and atmosphere. An untitled Rayograph from 1922 distinguishes itself by the presence of the artist’s hands that reach towards a silhouetted compass. The power of gesture and light here recalls the supernatural spirit of photography, the energy of one breath capture on paper in a moment’s time, suspended out of context for eternity.

In 1931, Man Ray was commissioned by la Compagnie parisienne de distribution d’électricité to create a series of images promoting the domestic use of electricity. The portfolio featured ten photogravures from multiple exposures and Rayographs that are charmingly campy. And later in the 30s, Man Ray began experiments in the tri-color process, a laborious effort that produced very carefully composed studies of Surrealist thought.

Throughout these years, Man Ray also photographed women, objects, and notable personalities including Sinclair Lewis, Jean Cocteau, James Joyce, Gertrude Stein, Joan Miró, the Marquise Casati, and Marcel Duchamp (as Rrose Sélavy), creating a timeless archive of treasures.

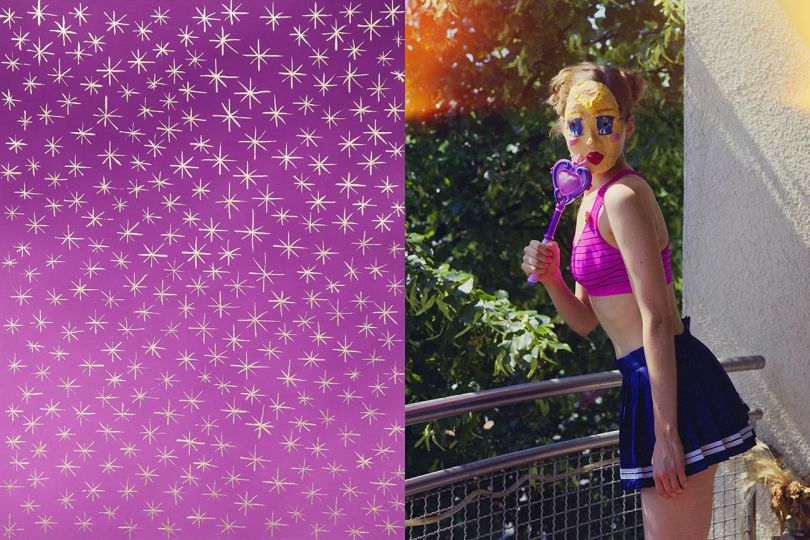

Fast forward eight or nine decades to 2011. Dennis Busch works in Germany, making his own brand of readymade photography, cutting and collaging and writing charmingly rude messages in white paint over many of the images. He constructs his images from photographs, revising our references until each work circles in on itself like a dream.

Busch’s work is a striking display of nihilistic collage art, absurdist sculpture, and abstracted photographs—many with messages for the public. An image of a medieval coat of armor, placed against a lavish red-orange backdrop, is casually adorned with the word iPhone. Juxtapositions seemingly so meaningless they make one pause in wonder, only to discover there is no “Why?”

Balancing this image is a photograph of an apple that has been given an unfortunate set of teeth. Well, only the top teeth, and those are not too fresh. The apple sits against a white backdrop, enjoying its time in front of the camera with a goofy grin you won’t find anywhere else.

Busch’s provocative iconography is at once awkward, edgy, aggressive, sexy, silly, and sometimes a little sentimental. Published in Back to Normal (Airbag Craftworks), Busch does not ask simple questions or offer easy answers, but happily thumbs his nose at convention, beauty, and formality. His work is a collection of imperfections, and a love of the absurd. Dada for your nerves.

Sara Rosen