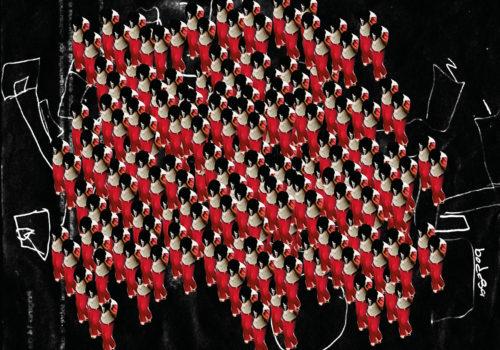

For 40-some exhalting years, Martha Cooper, the “Grande Dame of Hip Hop”, as she has once been called, has been documenting street art and graffiti artists. She has traveled all over the world since her first book, Subway Art, got published, in partnership with Henri Chalfant, in 1984. She has been on the street art circuit for so long so she has become a fixture of every event, the legal and illegal ones.

With the years, however, a certain weariness has taken place. In a recent interview in Atlanta, while covering Living Walls conference, Martha Cooper says that she feels less and less needed, “partly because artists are documenting their own art now and they are usually good at it.” If she still enjoys and dedicates most of her time to street art photography, she confesses that she also wants togo back to a more geniune and personal kind of street photography, one that is not based on somebody else’s art.

The opportunity to do something different came a few years ago, after her parents – who owned and operated a camera store in Baltimore since 1945 – passed away. She inherited a little money and thought about using it to start a project that she “would not have done otherwise and that she could continuously return to.” In 2006, she bought a one-bedroom house in a depressed, crime-ridden area of Baltimore, her hometown. She searched randomly, found some photos online of a house. “I went to the neighborhood and I saw a little boy jumping on a mattress and I am like ‘Yes’, that is what I want to photograph.”

Since buying the house, she has tried to return to it every other weekend, and made more than 160 trips so far, photographing the mundane life scenes, kids playing in the street, barbecues and birthday parties. She says that it has felt right since the beginning. New York, the city who made her famous, has become a little too “clean” for her. She was on the look for something a little “edgier.”

“It is really a personal project, one that I really have my heart into,” she says. “I now have met a lot of people and they call me ‘Picture Lady’, they are all asking me to take a picture of them and I always give them a picture back.”

She knows that this neighorhood is changing and she wants to be the one who will be documenting it, in the lineage of of Dorothea Lange’s and Walker Evans’ work.

“I think that 20 years from now, these pictures will be an interesting document, the same way that my pictures from the ‘70s are an interesting document [of that time]. I do photograph with that in mind.”

Martha Cooper envisions a hardcover book of 208 pages with her photographs along with some texts by neighborhood residents as well as well-known Baltimore writers.

Virginie Drujon-Kippelen