Evangeline and I first met in a moment of serendipity. In early 2012 I was skimming Longfellow’s collected works for passages to inspire a seemingly unrelated project about his birthplace and my adopted home, Portland, Maine. Only a few days earlier I had received notice of acceptance to an artist residency in Nova Scotia. My original intent was to photograph intertidal landscapes, but the approaching trip was about to take a much more ambitious direction.

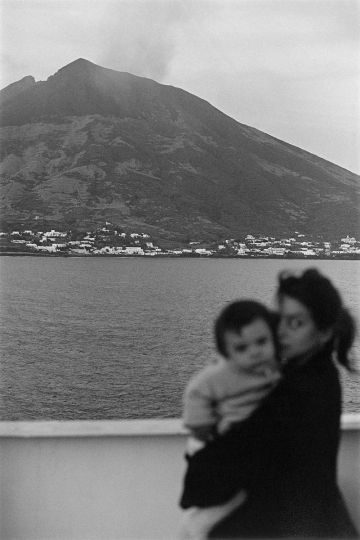

Having no prior knowledge of Evangeline or the expulsion of the Acadians—the historical event upon which the poem is based—I stumbled upon the epic and was instantly captivated. I studied up on the deportation and read the poem repeatedly. I went to work photographing the Canadian province in June with Longfellow’s words ringing in my ears. The mission to create a modern visual representation of the Acadia described by Longfellow in 1847 would draw me back to the region four times in as many years. The poet never visited Nova Scotia, but his vivid descriptions of the landscape could not have been more accurate. And the feelings of loss and desolation that the poem evokes still haunt the region today.

Nova Scotia is one of three provinces in eastern Canada known collectively as the Maritimes. It is a narrow peninsula almost entirely surrounded by the sea. Most of the images in this book were taken along the roadway dubbed the Evangeline Trail, the name being evidence of the importance of Long-fellow’s poem to the history of the province. This road traverses the western shore from Yarmouth in the south to the hallowed site of Grand-Pré on the shore of Minas Basin, a branch of the Bay of Fundy. Here, the largest tidal range in the world transforms the coastal landscape by exposing and recovering vast expanses of the seafloor twice daily. It feels as if the whole ocean is breathing in and out, in a semi-diurnal cadence.

The rich valleys and lowlands are highly cultivated, while still feeling wild. Eagles hunt from coastal pine trees, seals lounge on sun-warmed rocks, and the wind can be unrelenting. Fog banks lurk around lush green headlands, creeping into coves and sweeping across the flats. Nestled into the scenery, a stoic culture, descended from Acadian settlers who were allowed to return from exile in the late 18th century, has adapted to living in harmony with the harsh elements. Life for the Acadians has never been easy. They have fought and toiled for everything they have. But as one travels through Nova Scotia today, the abundance of vacant properties and waning commerce in some areas suggest that forces beyond their control are once again putting a strain on the peaceful enclave.

Longfellow’s Evangeline is based on a true story about loss and displacement. It is about a thriving village raised out of an inhospitable landscape by an industrious group of settlers, then eliminated in one abrupt event. Today along the Western Shore, a similar story is slowly unfolding. Many communities that were built with pride by a generation that banded together to reclaim their homeland a century ago are again declining in population as economic hardships stifle growth. The visual narrative I have weaved implies that these conditions have brought on a new migration of Acadians away from their homeland. It has been a gradual exodus compared with the Expulsion, but disturbing nonetheless. The decaying Victorian houses, deserted commercial fishing ports, and enchanting primordial landscapes—these are all verses in my own modern tale of Acadia.

Mark Marchesi

Mark Marchesi, Evangeline

Published by Daylight Books

$45