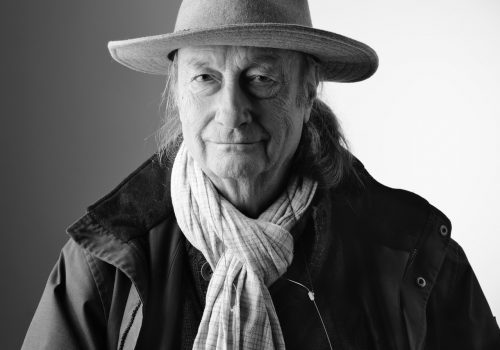

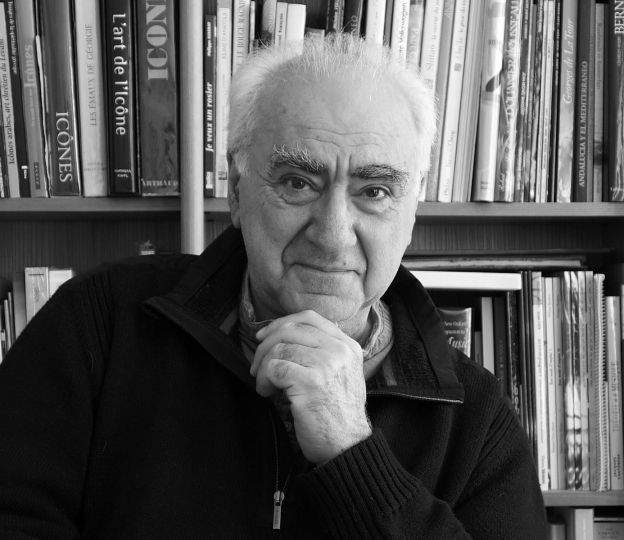

Photographer Marc Garanger, well known for his portraits of Algerian women taken during the Algerian war, died on April 27, 2020 in Lamblore (Eure-et-Loir) he was 85 years old. Historian Françoise Denoyelle, who knew him in the 1970s and attended him all his life, traces his journey for A l’oeil.

Marc Garanger, dignity above all else and therefore prefers empathy.

In the history of photography, Marc Garanger will remain the author of Femmes algériennes (1982) which is not much in terms of the importance of his work, but the density of the subject, the accuracy of the gaze of this already professional young man carried high the requirements which will nourish his work to come.

I met Marc at the end of the 1970s, he published Togliatti (1965) a report with his friend the writer Roger Vailland on the funeral of Palmiro Togliatti, secretary general of the Italian Communist Party. He told me about the trip with Vailland that he had known since 1957-1958. I looked at the images of the militants, the gesture of the working world worthy in pain. They were reminiscent of the images of Capa and Chim of the international brigades leaving Spain in October 1938. But it is to Vailland’s memories in Ecrits intimes (1972) that we must now return. “The last opportunity undoubtedly to attend in the West a great popular and significant show for those who are involved (…). The evening of August 21st,we decided around midnight to leave for the funeral of Togliatti with Janine and Marc Garanger, and Rozir and Violette in their 4 CV (…) amazing and proud beauty of the companion of Togliatti at the funeral, political challenge at the same time as widowhood, when feelings and history become one. That same year Garanger had accompanied Vailland to Greece. He made numerous portraits of the writer, particularly during his last year in 1965.

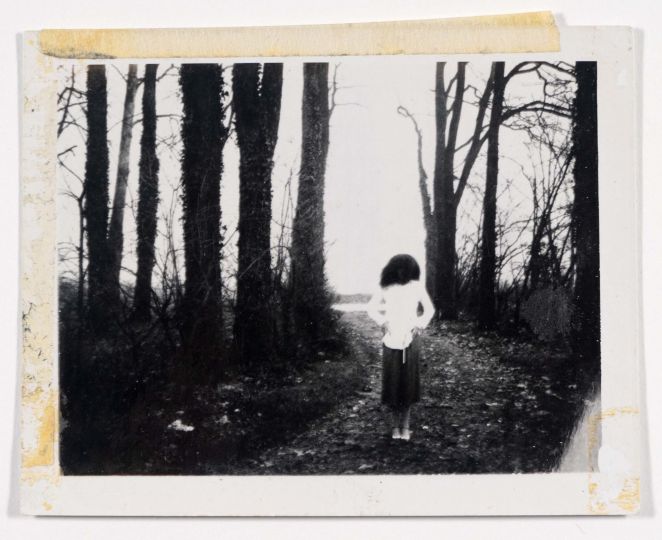

His portraits of Algerian women, Garanger produced them during the Algerian War, between March 1960 and February 1962. At 25, after having exhausted all possible reprieve, he was integrated into the 2nd infantry regiment stationed in the sector of Aumale, today Sour El Ghozlane. Professional photographer since 1957, anti-colonialist, he was drafted in a war that was not his own. Becoming an official photographer of the regiment, photography first turn out to be a safety valve for Garanger then a weapon which he intended to use at one time or another.

“I photographed everything I could of the lives of these people whom we French destroyed by pretending to act for the good of the people”. But my respect went to those who were subjected to this, not to those who imposed it on them, ”he declared to Clothilde de Ravignan.

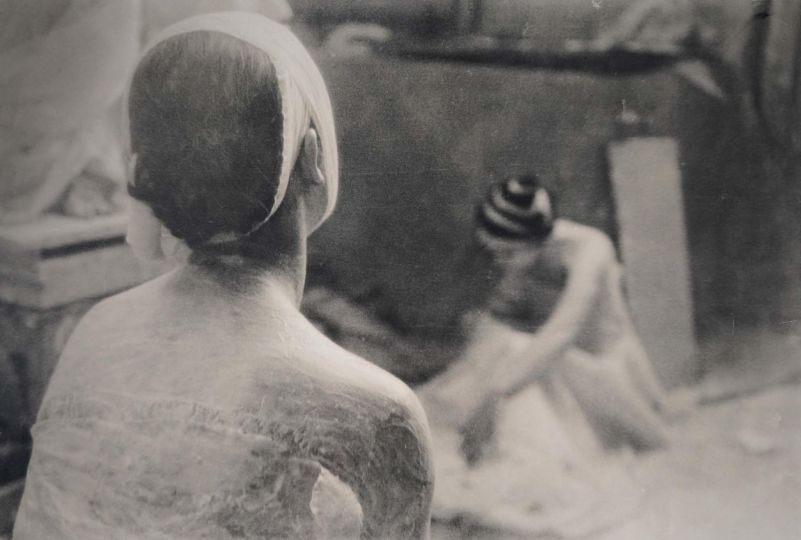

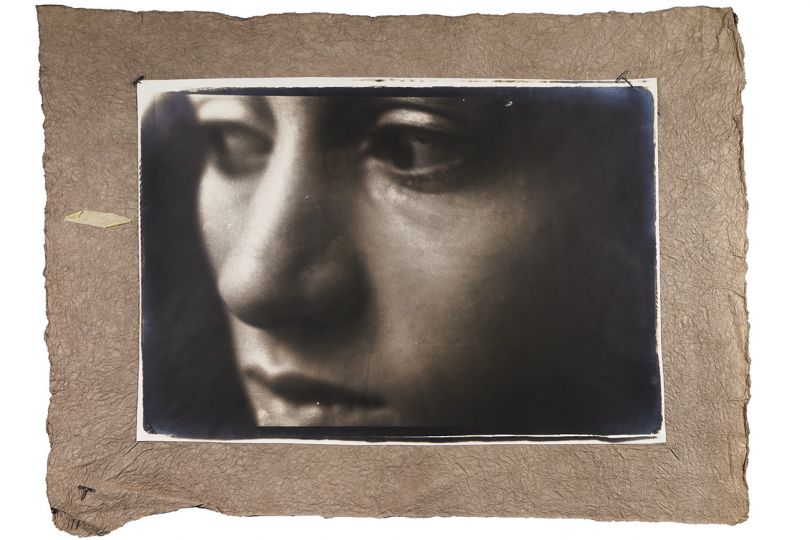

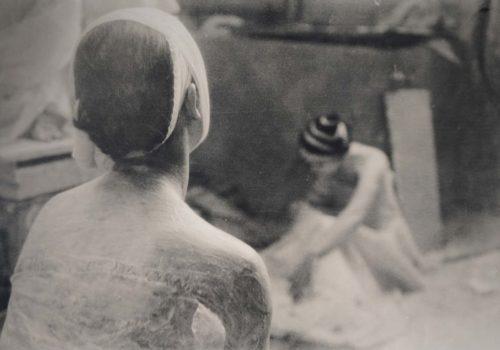

Sent to Aïn Terzine for ten days, he drew the portrait of more than two thousand Algerian women who had to reveal themselves to meet the identification requirements ordered by the commander. The photographs would be used for identity papers. Remembering the work of Edward Curtis on the Indians decimated by the Americans, he produced portraits to bear witness to “the rebellion of these women” and vowed tolet people know about their dignity and their struggle.

In 1961, during his only leave in France, Garanger met Rober Barrat, journalist, director of the Paris office of the weekly Afrique Action and endorser of the Manifesto of the 121 for which he was briefly imprisoned,who advised him to go underground to Switzerland to offer some portraits of Algerian women at L’Illustré suisse. On his return to France, he learned that the week following his meeting with the editorial staff, six portraits were published in double page with a text by Charles-Henri Favrod then close to the FLN and author of The Algerian Revolution in 1959 and The FLN and Algeria in 1962. During the summer of 1962, in Meillonnas, at Vailland’s, Garanger presented his photographs to Francis Jeanson, still clandestine after the trial of his network of underground money carriers. They mentioned the latest publication by Dominique Darbois, clandestine, also for the same reasons. The work of this young woman photographer Les Algeriens en guerre polemical paper released in Italy is banned in France (1961).

In 1965, Pierre Gassmann, director of the Picto laboratory, helped Garanger to put together a portfolio. He reworked on his Algerian portraits to which he added the images of Italian communist militants. The portfolio required substantial work on the portraits, whose format and background he was reconsidering. In 1966, he won the Niépce prize. The photographs were taken up in the national and international press. Paris Match distributed it widely. Claude-Olivier Stern presented them at the Maison de la culture in Le Havre in 1970, at a time when photo exhibitions were rare and had them circulating in other Maisons de la culture.

In 1974, a journalist from Jeune Afrique informed him that Major Ben Chérif, whom he had photographed in his cell at Aumale, was now a member of the Revolution Council close to Boumedienne. He made contact with him. An invitation and an exhibition in Algeria followed.

It was not until 1981 that Alain Desvergnes presented in the ancient theater one evening, “Algerian War / Algerian Revolution” at the Rencontres internationales de la photographie in Arles. A hundred portraits weave the litany of these women frozen in their accusing silence. They were followed by portraits of maquisards with a triumphant smile by Mohamed Kouaci. A tradition that forged the exceptional moments of the Rencontres d’Arles, Garanger read the text that will latter appear in the book. The projection followed by a tense silence was a revelation for many. A vivid impression of a rare moment, of work that commanded respect, so much was missing from the collective unconscious of images of this war which did not even carry its name, decked out as it was by the term “events” by the power.

“Why are these women so moving?” Asked Hervé Guibert, comparing the images of Elisabeth taken by Kertész and the Algerians from Garanger.

In 1981, Arles was buzzing and more successful years began for Garanger. His work is recognized. In 1982, Claude Nori, present during the Arles projection, published Femme algériennes 1960. The portraits were exhibited the following year at the National Photography Foundation in Lyon, Pierre Devin presented them at the Regional Center for Photography in Douchy-les- Mines and Jean Dieuzaide at the Chateau d’eau in 1986. Algerian women were presented in more than 300 exhibitions, notably at the Venice Biennale, at the Museum of Modern Art in San Francisco and in New York.

In 1984, was published the Algerian war seen by a conscript, with forewords by Francis Jeanson, text and photographs by Garanger.

“To survive, to express myself with my eye, since words are useless, I take my camera. To scream my disagreement. For twenty-four months, I did not stop, sure that one day I could testify, tell with images. ”

Reluctance of the editor, embarrassed indifference of most commentators, silence. Another past that does not pass. Garanger is bruised. His images trigger no reaction, no testimony from the conscripts as he had hoped.

Jules Roy nevertheless made a glowing article about it. In 1987, he offered to return to Algeria, to Aïn Terzine, to find the women photographed, to make a film for television, but the project was unsuccessful. Algeria remains a subject not to be talked about or seen too much. In 2004, he went in search of these women for Le Monde, 44 years after having photographed them. Without name, without address, he traveled through Kabyle villages, photographs under his arm, found some of them. Same clothes, same jewelry, but radiant poses. Garanger captioned a selection of 21 shots for everyday life.

In 1990, the La Boîte à documents editions published Femmes des Hauts Plateaux, Algérie 1960, a set of black and white and color reportages on village life as he captured it during his wanderings outside the patrols. A text by Leïla Sebbar on the second generation of Algerians in France served as a counter field. To conclude with what marked him so deeply, he published Marc Garanger, back in Algeria with a text by Sylvain Cypel in 2007.

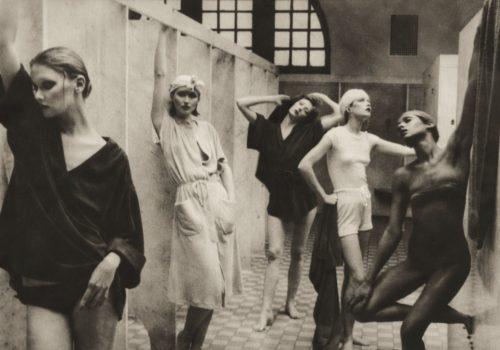

But the work on Algeria is only a part of Garanger’s work. With the Niépce Prize grant, in the middle of the cold war, he left for the other side of the iron curtain in Czechoslovakia. First of many reports on eastern countries. He explored almost all the republics of the former USSR. In 1992, at the end of Regards vers l’Est, we exchanged our conclusions on these countries which he had travelled so much. In 2003, he collected his best shots for Russia, the face of an empire. He made a projection for Gens d’images at the MEP (European House of Photography) in 2009.

A man of the left, of conviction, he was his whole life, documenting The Chain of Hope in Cambodia in 2003-2004, settling down for a photographic residency in a home for immigrant workers in Lyon. He had supported the association from the start (ADIDAPP then APFP) to defend and promote photographic collections.

He had left Paris for the country where he could work more comfortably on his archives. In the years 1978-1980, he was a pioneer and had experimented with videodisc to archive his million negatives. In 1988 his first film Regard sur la Planète, 54,000 photographs by Marc Garanger was followed by five others on the Death Valley, the Taiga, the Ivory Coast … The time to work on his archives having passed, he was still at work. His son Martin watches over.

Farewell friend, Farewell Marc,

The women say thank you Monsieur the photographer.

Françoise Denoyelle for A l’œil

Françoise Denoyelle is a historian. Professor of distinguished Universities (ENS Louis-Lumière), associate researcher at the Center for Social History of the Twentieth Century, University of Paris 1 Panthéon Sorbonne / CNRS. She has published around thirty books including Studio Harcourt (1992), François Kollar. The choice of aesthetics, (1995), La Lumière de Paris 1919-1939 (1997), News and propaganda photography under the Vichy regime (2003), Harcourt 1934-2009 (2009), La Dynastie des Terraz (2010), Le Siècle de Willy Ronis (2012), Boris Lipnitzki le Magnifique (2013), La Vie led la danse, text by Germaine Krull established and annotated by Françoise Denoyelle, 2015, Jean Marquis (2016), André Malraux, Portraits chosen by Françoise Denoyelle, 2017, Arles Les Rencontres de la photographie 50 years of History, 2019, Arles Les Rencontres de la photographie Une histoire française, 2019.