It is difficult to write or talk about Malick Sidibé. There is the risky stereotypical description of him as one of the greatest African photographers of his generation, or worse, an amazed description by those saw his Bamako series from the 1960’s and ‘70’s, with girls in balloon dresses or bare-chested on the banks of the Niger. They will say to you, smiling, “You westerners continue to think that in the ‘60’s Africans were living naked in the trees, but I can assure you, this was not the case.”

It becomes even harder to talk about him if you know him: Malick Sidibé is a surprising man, from all perspectives. Perpetually smiling, always ready, a tireless intellectual curiosity more likely in a young boy than in a 75 year old man, religious, but open to all forms of spirituality. And then there are the stories that he loves to tell: those of the people in his pictures, for example. He knows all of their names, their jobs, their families. Archives of real life in today’s Mali. Stories of his childhood filled with vengeful elephants and killer pythons. Few people know how to tell a story as well as Malick, bloody and tragic, that all finish with a smile. Madame Fanta, one of his wives, once told me “God smiled on Malick”. Those who know him can believe it, hence the difficulty of writing about him objectively: falling in love is rather easy.

“I have always been a talented observer. I love looking at people, trying to understand them. In Africa, it is important to respect your elders, it is part of our tradition. I have always had this respect, even at the beginning of my career, I was older than the boys and girls I photographed at parties, but I never wanted their reverence: that would have made them uncomfortable for the pictures, I would have lacked the spontaneity I was looking for.

I always loved being around young people: they are the source of new energy, the changes that make the world evolve. I don’t think it is very logical to look to the past: it is important to know where we come from, but it is as important to be able to progress. And that power is in the hands of future generations. At the end of the ‘50’s, when I started working, everyone in Bamako knew me, and children still yell in the streets “Malick, Malick!”. It makes me happy, I don’t want them to be intimidated. I am known all over the country, people still come from afar, from abroad, and not just from Europe or the United States, to have their pictures taken. It all started by a mysterious drawing,” he says.

Malick Sidibé was born in 1936, in Soloba, a village about 300 kilometers outside of Mali’s capital city of Bamako. He is of the ethnic group Peul, formerly nomads and traditionally animal herders, the second largest ethnic group after the Bambara. “My father decided I would be the son who would study. He sent me first to Yanfolila, to the Père Blanc school, then to Bougouni, 160 kilometers outside of Bamako. We went to school on foot, stopping often, it was an adventure. I was talented at drawing and one day the school principal asked me to make three paintings to offer to the Governor of the Sudan Colonies (the name of Mali before independence from France) who was visiting. Thanks to his help, I was admitted to the Fine Arts School of Bamako in 1952. Three years later, I had a diploma in jewelry making, I was their best student, but I wasn’t satisfied. Tradition has it that the Peul are not artists, but breeders. When the school sent me to decorate the store of Gérard Guillat-Guignard, a photographer affectionately known throughout Bamako as Gégé la pellicule, I accepted with curiosity. At the end of my job, he asked me to stay on board. I started working as a cashier, but quickly became his assistant. I loved photography, it was a fast way of making a portrait, far more quickly than by drawing. In 1956 I bought my first camera, a Brownie Flash (that is still in my studio) with which I started a few reportages. Gérard Guillat-Guignard gave me a percentage of the earnings. When he retired at the end of the ‘50’s, he offered that I run his shop. I didn’t feel ready. Finally, in 1962, I opened the Studio Malick in the working class neighborhood of Bagadadji : I began taking pictures of the Bamako youth. With my bicycle, I could cover up to five events a day, then there were ceremonies and baptisms, weddings…”

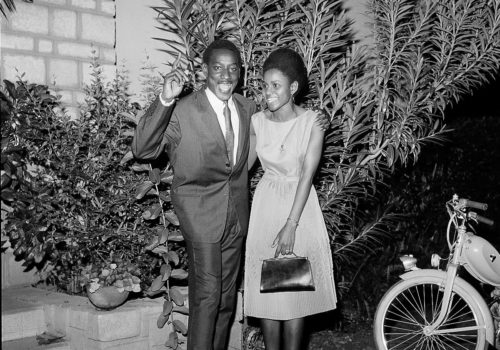

He frequented parties where youngsters dressed western style and danced to records: his pictures provide a group portrait of young and happy people, confident in their future. Clubs with exotic names opened throughout the city, not one event took place without Sidibé being invited: his reputation was so great that if he couldn’t come, the party time and place would change to accommodate him. The pictures of this period are a true testimony to the country’s history.

“Late at night I would return to the studio to develop negatives and print contact sheets, then after having slept a few hours, I would wait for clients to come select the portraits they wanted printed, then delivered. The ‘60’s and ‘70’s were happy years, but difficult. I spent months at a time without visiting my family. It was easy to have fun, with little money you could spend a week in the clubs, drinking and offering roast chicken to the girls you liked. Surprise parties were even cheaper.

Everyone wanted to dance, everyone wanted to look smart. The true Malian revolution was not political, it came about through western music. Before, we couldn’t dance together. With Cuban rhythms, the Beatles or James Brown, the boys and girls touched, approached each other. The elderly, the parents, didn’t approve, but they couldn’t resist the changes provoked by notes on the record players. It was very pleasant, we knew what was happening in Europe and the United States thanks to the cinema. In town, there were excellent tailors who could make bell bottom pants or balloon dresses in no time at a low price. Sometimes friends had identical clothes made, with the same fabrics. A tradition that lives on for important occasions. During the hot season, the parties took place along the Niger river, just a few kilometers from town were beautiful beaches where the youngsters spent their days.”

Towards the end of the ‘70’s he decided to work only on studio portraits. The procedure was simple but effective: after a short conversation with his subject, to put him at ease, Sidibé chose the pose, capturing in a short moment the essence of their personality. The studio is currently at the same address, not much has changed, even if digital photography has reduced the workload for portraitists.

“I am proud to be a photographer, because photography does not lie, especially the black and white that I always used. That is why I insist firmly that my photography is more sincere, authentic and direct than any words. It is simple, anyone can understand it and it tells the story of a time period without cheating. I have never taken academic pictures, during my youth we couldn’t see books and magazines about photography, we didn’t know how other photographers worked. My fine arts training in painting and drawing helped me compose my pictures and choose the poses for my subjects.”

Man has always looked for immortality in painting, poetry, or writing, but in the past, only the king and the affluent could pay for a portrait. My father never saw his own image, except in a mirror or in water. Photography is a way to live long, well after death. I believe in th power of pictures, that is why I spent my life trying to portray people in their best light, trying to bring out as much beauty as possible. That is why I try to make my subjects feel comfortable, because life is God’s gift and it is better if we approach it with a smile. Images of Africa are too often full of pain and misery. It would be stupid to deny these realities but Africa is more than that and I always wanted to show that in my pictures. Here, people are only poor if they have nothing to eat, I often see people with beautiful houses and desperate lives.”

In 1994, during the first edition of the Rencontres de la photographie de Bamako, the portraits of Sidibé and Seydou Keïta (another major portraitist in Bamako, 12 years his senior, deceased in 2001) were exposed for the first time. Journalists and western critics discovered their talents. Shortly thereafter, Sidibé’s pictures were in Paris, at the Fnac Etoile then the Fondation Cartier for Contemporary Art, in no time museums and galleries around the world presented his work. For Malick Sidibé, a new life began with travels around the globe, conferences, prizes, events he lived with the wisdom and simplicity that make him a great man. These past few years, he holds classes and gives seminars in the art and photography schools of Bamako.

“I have been traveling for the past few years, bringing my African pictures to Europe, Asia, the United States. I am proud and happy of the recognition and thank God, I am just a small element of my destiny. I love to see new cities, so beautiful and different from my own. But I can never leave Bamako, it’s streets of red dust, the treasure of Africa. I love to meet young peole, share my experiences and answer their questions. Like I said at my acceptance speech for the Biennale de Venise prize: I am just a small African that told the story of his country, still surprised by the world’s interest. Today, some call me an artist, but I prefer photographer”. Today, Sidibé is considered Africa’s greatest living photographer. The Biennale de Venise offered him a Lion d’Or for his career, the first time it was presented to a photographer; In 2003 he won the Hasselblad prize in Sweden, in 2008 the ICP award in New York, in 2009 PhotoEspaña-Baume & Mercier de Madrid and, in 2010, the World Press Photo for arts and performances. Numerous books about his work have been published in Europe, the United States, and Africa.

The photographer continues to live and work in Bamako.

Laura Incardona

Journalist and exhibition curator.