Fundacion Mapfre is presenting for the first time in Spain the work of the photographer Gotthard Schuh (Berlin-Schöneberg, Germany, 1897, Küsnacht, Switzerland, 1969). The exhibition has been organised in close collaboration with the Fotostiftung Schweiz in Winterthur, from where the works have been loaned, and is curated by its director Peter Pfrunder.

The exhibition includes 113 photographs, ninety-three by Gotthard Schuh dating between 1929 and 1956, and twenty additional images by Robert Frank, Werner Bischof, Jakob Tuggener and René Groebli. The result is to present Gotthard Schuh alongside the most important Swiss photographers of his day, all members of the College of Swiss Photographers (Kollegium Schweizer Photographen) in the 1950s.

Gotthard Schuh (1897-1969) was one of the most important Swiss photographers of the 20th century. In 1930 he interrupted a promising career as a painter to devote himself fully to photography. Schuh enthusiastically participated in the aesthetic revolution that took place in the world of photography in the late 1920s and which championed a “new vision”. The flourishing field of photojournalism offered him an opportunity to express his visual ideas, with the magazine Zürcher Illustrierte setting the standards within Switzerland. Its editor-in-chief, Arnold Kübler, used the most talented Swiss photographers to redefine photo-reportage as a narrative form and Schuh became a staff photographer from 1932.

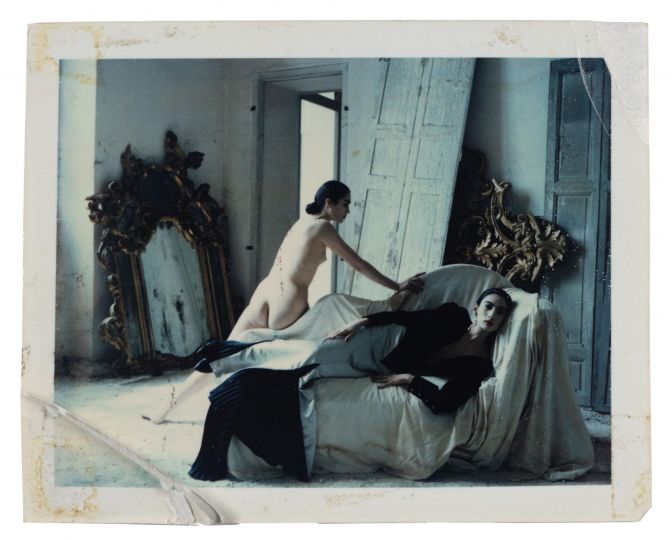

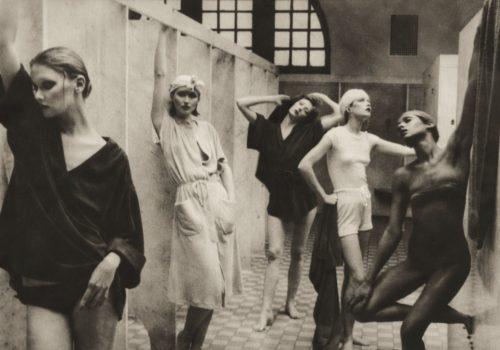

Alongside his activities as a reporter, Schuh always aimed to escape from everyday reality. In the early 1930s he spent various periods in Paris where the ideas of the “new vision” prevailed and where he developed a style that could be described as “poetic realism”. Emotional expressivity, a sense of specific atmosphere and psychological awareness became key elements in his work. Schuh photographed night-time scenes and immersed himself in the world of women in search of a vibrant eroticism, making human relations his preferred theme. Prevailing motifs in his imagery were women, lovers and crowds of people that convey a vibrant sense of life.

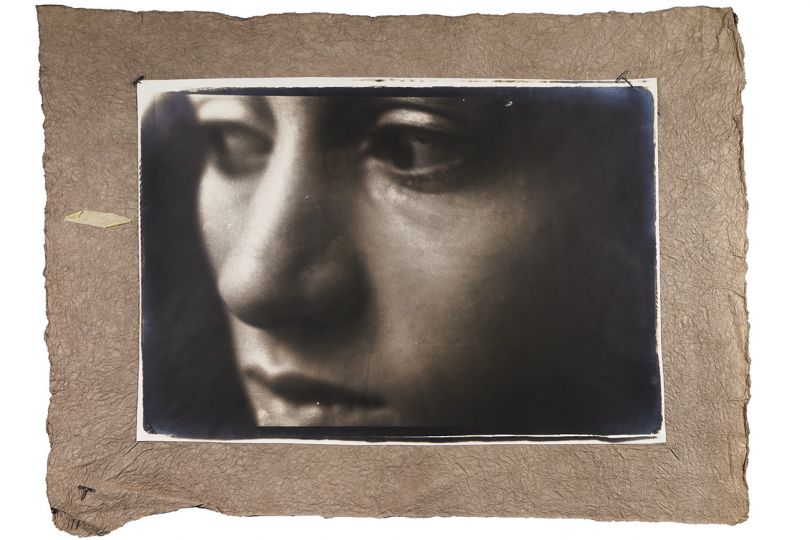

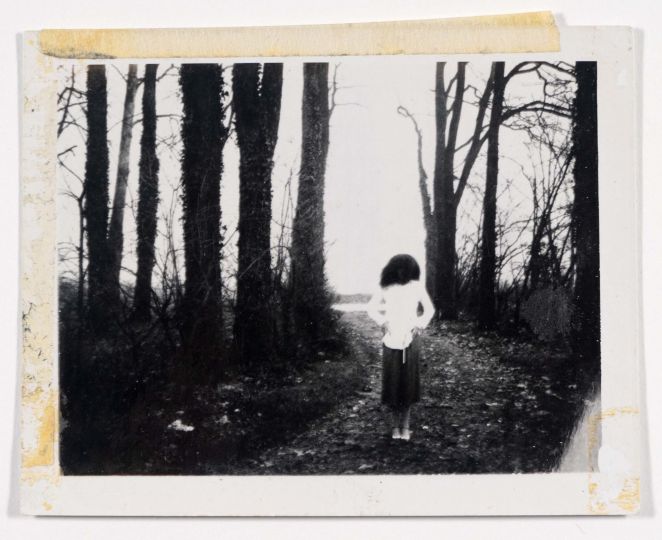

When Schuh began to take photographs in 1930 he fully immersed himself in the innovative spirit associated with the “new vision”. In his published works optical effects and a pronounced sense of design played an important role. Schuh, however, did not only focus on depicting unusual compositions or representing the surface of things in a precise way. Above all he aimed to convey the sensations of everyday life in scenes that apparently lacked drama but which were imbued with a mystery that created a marked sense of suspense in the manner of the opening sentence in a story.

During the time that he spent in Paris in the 1930s Schuh was inspired by the pleasure of living in that vibrant city and he began to focus on people as a subject. The atmosphere of particular places and lyrical expressivity became the motor of his work. Women, couples and streets scenes were favoured subjects, while Schuh was always attracted to eroticism. With a particular sensitivity to the changing moods of city life, he also explored Zurich at this period where he lived and worked for most of his life. In 1935 the city became the subject of his first book of photographs, a work that goes far beyond a merely touristic or documentary record.

Schuh’s photography in the 1930s was also notably influenced by his activities as a photo-journalist. Commissioned by the Zürcher Illustrierte, he produced photo-reportages from around the whole of Europe, covering social, cultural, sporting and political subjects, among them the rise to power of the Nazis in Berlin. In 1941 he abandoned the stimulating life of an independent reporter and became the first graphic editor of the Neue Zürcher Zeitung.

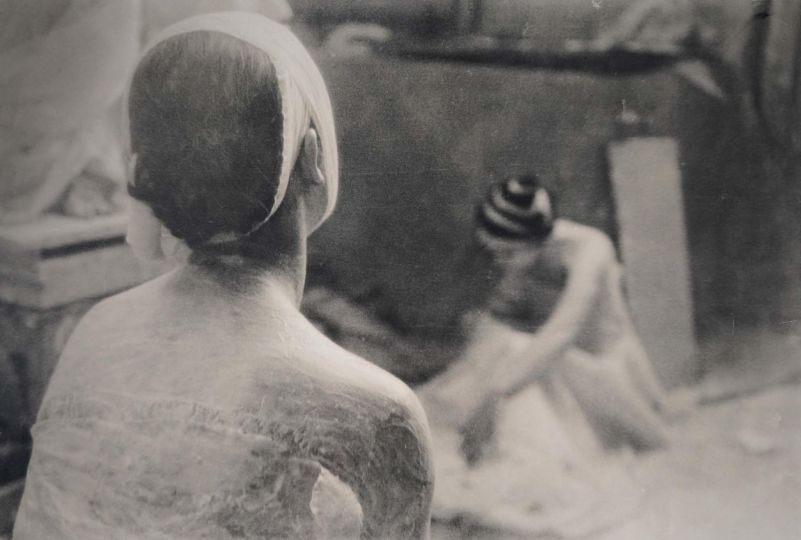

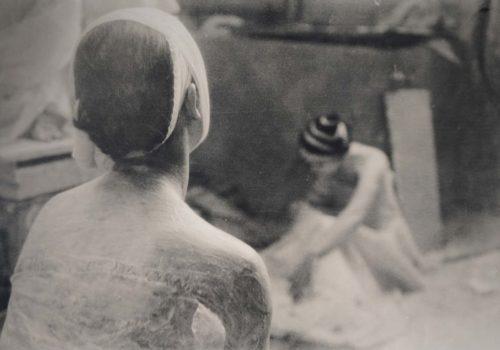

In March 1938 Schuh left for Singapore, Java, Sumatra and Bali on a trip that lasted eleven months. On his return he published the book Inseln der Götter [Islands of the Gods] in 1941. What seems at first sight to be an extensive, documentary photo-report reveals itself on closer examination to be a subjective travel account; an accomplished mixture of reportage and intimate observation and of fact and imagination. Schuh presents the “Islands of the Gods” in three principal chapters: a celebration of nature and the landscape and of the local population and local cultures; work and everyday life; and festivals and religious ceremonies. The detailed and highly personal text of the book allows us to speculate that Schuh used his lucid, sensual photographs to create a world in opposition to a possible existential crisis as he engaged in a struggle against his own darker sides.

Inseln der Götter is one of the best known and most successful books of Swiss photography, a fact that is even more striking given that it was published in difficult times during World War II. While from the mid-1930s Swiss art revolved increasingly around the country itself, in this work Schuh focused on an apparently unsullied paradise located at the other side of the world. Schuh’s images have been enormously influential, in part for their poetic and metaphorical nature rather than their historical, geographical or ethnological context. They have become symbols of the quest for beauty and the longing for interior harmony.

As graphic editor of the Neue Zürcher Zeitung, Gotthard Schuh was one of the co-founders of Das Wochenende, a magazine-type supplement that became highly regarded for its photography in the 1950s. In it he published reports by young colleagues and by internationally renowned photographers. His own work was published in books on Italy (1953), Ticino (1961) and Venice (1964). Schuh’s most important publication of this period was, however, Begegnungen [Encounters] of 1956 in which he combined old and recent photographs in a work of free association that is both innovative and self-contained. Its images focus on the theme of the encounter: between a man and a woman looking for each other (or separating), or between the photographer and people, landscapes and things.

Through his overtly subjective gaze on these encounters, Schuh became an important influence for young Swiss photographers. Robert Frank also acknowledged him as a mentor and stated that he was impressed by his type of emotional expression and commitment to interior truth. A friendship based on great mutual respect developed between the two photographers from 1952 onwards. When Frank published his emblematic book Les Américains in 1958 Schuh immediately realised that Frank had created something completely ground-breaking and he was profoundly moved by Frank’s unvarnished sincerity. Above all, the work of the two photographers shares a facet of melancholy.

In 1950 Schuh co-founded the Kollegium Schweizerischer Photographen association together with the photographers Werner Bischof, Paul Senn, Jakob Tuggener and Walter Läubli. Characterised by a rather rigid type of organisation, it brought together eminent photographers and promoted original photography with artistic aspirations. Members met regularly in sessions that ended with a meal and an exchange of ideas. Their ideas on the quality of photography were presented in two exhibitions held in the Helmhaus in Zurich in 1951 and 1955; they attributed great importance to individual and subjective expression and to photographs that achieved a powerful effect but were devoid of a particular purpose. Schuh explained these concepts: “Almost all photographs have been taken with a specific end in mind and had missions to fulfil, they had to communicate this or that as part of a report or as individual images and almost all of them functioned to express a text visually. Why not bring together in this exhibition photographs that are freed from any final intent? An intensely expressive photograph, correctly perceived both formally and emotionally, reliant on its inner tension, has a life of its own.” In the second exhibition, Photography as Expression, the Kollegium also included work by various young photographers including Robert Frank and René Groebli. The images exhibited are striking for their sensuality and for their range of dark, melancholy tonalities. With works such as Funeral, Barcelona (1951) and Valencia (1950), Robert Frank was perhaps the one who most pursued the expression of that existential melancholy that would continue to characterise his later output. Despite its success with the public, the Kollegium broke up in 1956 due to differences of opinion among members.

Gotthard Schuh

Until February 19, 2012

Fundacion Mapfre

Sala AZCA Avenida General Perón, no 40

Madrid