Louis Blanc (1811-1882) was a French politician and historian. A socialist that favored reforms, he called for the creation of procedure cooperatives in order to guarantee employment for the city poor.

He was born in Madrid under French rule in 1811, his father held the post of inspector-general of finance under Joseph Bonaparte. Failing to receive aid from Charles André Count Pozzo di Borgo 1764-1842), his Corsican mother’s uncle, Louis Blanc studied law in Paris, living in poverty , and became a contributor to various journals. In the Revue du progres, which he founded, he published in 1839 his study on L’Organisation du travail. The principles laid down in this famous essay form the key to Louis Blanc’s whole political career. He attributes all the evils that afflict society to the pressure of competition, whereby the weaker are driven to the wall.

He demanded the equalization of wages, and the merging of personal interests in the common good– “à chacun selon ses besoins, de chacun selon ses facultés,” which is often translated as “from each according to his abilities, to each according to his needs.” This was to be affected by the establishment of “social workshops,” a sort of combined cooperative society and trade-union, where the workmen in each trade were to unite their efforts for their common benefit. In 1841 he published his Histoire de dix ans 1830-1840, an attack upon the monarchy of July. It ran through four editions in four years.

In 1847 he published the two first volumes of his Histoire de la Revolution Française. Its publication was interrupted by the Revolution of 1848, when Louis Blanc became a member of the provisional government. It was on his motion that, on 25 February, the government undertook “to guarantee the existence of the workmen by work”; and though his demand for the establishment of a ministry of labor was refused — as beyond the competence of a provisional government — he was appointed to preside over the government labor commission (Commission du Gouvernement pour les travailleurs) established at the Palais Luxembourg to inquire into and report on the labor question.

The Revolution of 1848 was the real chance for Louis Blanc’s ideas to be implemented. His theory of using the established government to enact change was different from those of other socialist theorists of his time. Blanc believed that workers could control their own livelihoods, but knew that unless they were given help to get started the cooperative workshops would never work. To assist this process along Blanc lobbied for national funding of these workshops until the workers could assume control. To fund this ambitious project, Blanc saw a ready revenue source in the rail system. Under government control the railway system would provide the bulk of the funding needed for this and other projects Blanc saw in the future.

When the workshop program was ratified in the national assembly, Blanc’s chief rival Emile Thomas was put in control of the project. The national assembly was not ready for this type of social program and treated the workshops as a method of buying time until the assembly could gather enough support to stabilize themselves against another worker rebellion. Emile Thomas’s deliberate failure in organizing the workshops into a success only seemed to anger the public more.

The people had been promised a job and a working environment in which the workers were in charge, from these government funded programs. What they had received was hand outs and government funded work parties to dig ditches and hard manual labor for meager wages or paid to remain idle. When the workshops were closed, the workers rebelled again but were put down by force by the national guard. The national assembly was also able to blame Blanc for the failure of the workshops. His ideas were questioned and he lost much of the respect which had given him influence with the public.

Between the “sans-culottes”, who tried to force him to place himself at their head, and the national guards, who mistreated him, he was nearly killed. Rescued with difficulty, he escaped with a false passport to Belgium, and then to London. In his absence, he was condemned by a special tribunal at Bourges, in contumaciam, to deportation. The events of 1848 introduced more radical ideas to America’s progressives. Revolution broke out in France, Austria, Italy, and the German states.

Most of the insurgents hoped to establish representative governments in Europe, governments which would guarantee freedoms of the person and the press. Members of disempowered ethnic groups demanded the right to form nations of their own. Some revolutionaries expressed more radical demands. Workers in Paris proclaimed that all men should have the “right to work,” and in response the revolutionary government established National Workshops, one of the world’s first experiments in state socialism.

Though the National Workshops and most of Europe’s revolutions failed, in the years that followed the ideals of 1848 remained alive in the United States. Readers of greeley’s New York Tribune, for example, heard from louis Blanc, a member of the 1848 French revolutionary government who had helped to establish the National Workshops. Blanc believed that the state could play a role in easing the plight of the urban poor by controlling the means of industrial production.

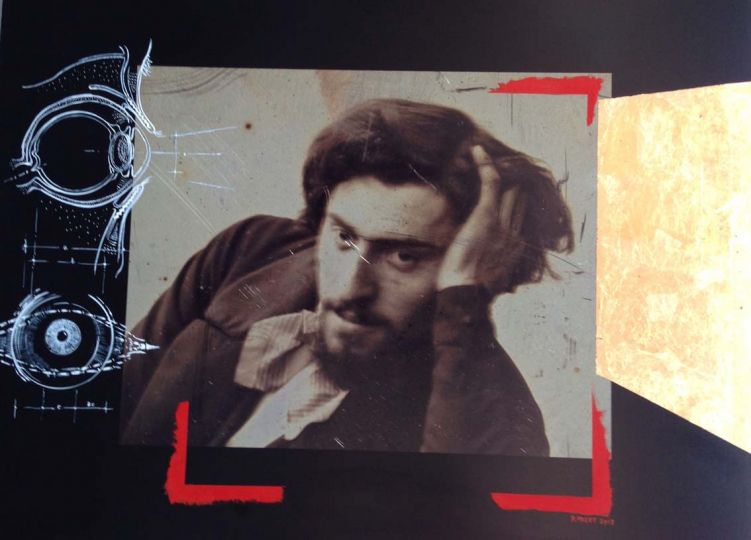

Serge Plantureux

Serge Plantureux is a French photography collector living in Paris, France.