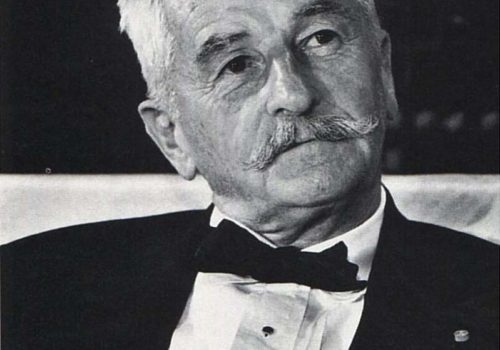

There is no assurance that when people say no to a picture, that they really mean no. But there are people who just hate to sit in front of a camera. I’m one of them. William Faulkner is another. He proved to be one of the best and dearest subjects I ever had. Still, it was difficult to reach him. We had gone to his publisher and to many others. Nobody could get to him. Finally, his son-in-law invited me to go to West Point, where Faulkner was to lecture to English classes on the novel. There I was told that I would be put in a room with him, and I would have only three minutes by the watch. That I was not to speak to him. I agreed to all these things, and I got into the room before Faulkner, set up my lights and waited. I was shooting color. Then Faulkner came through the door and walked directly to me with his hand out and shaking hands said, “Mr. Mydans, how good of you to come all the way up here to photograph me.” While I was photographing him, he broke the rule West Point had established that we would have no conversation, by speaking to me first, even though I didn’t speak to him. My feelings for him are very warm. His portrait was on the cover and was already on the presses when the editors scrapped it for the hydrogen-bomb test in the Pacific. Someone at the office kindly saved a printed copy of the cover for me, which I still have among my favorite pictures. The picture was later used at his death, but it wasn’t used as a cover.

(Interviewed on January 9, 1992. Excerpted from: John Loengard, LIFE Photographers: What They Saw, Boston, A Bullfinch Press Book, 1998)