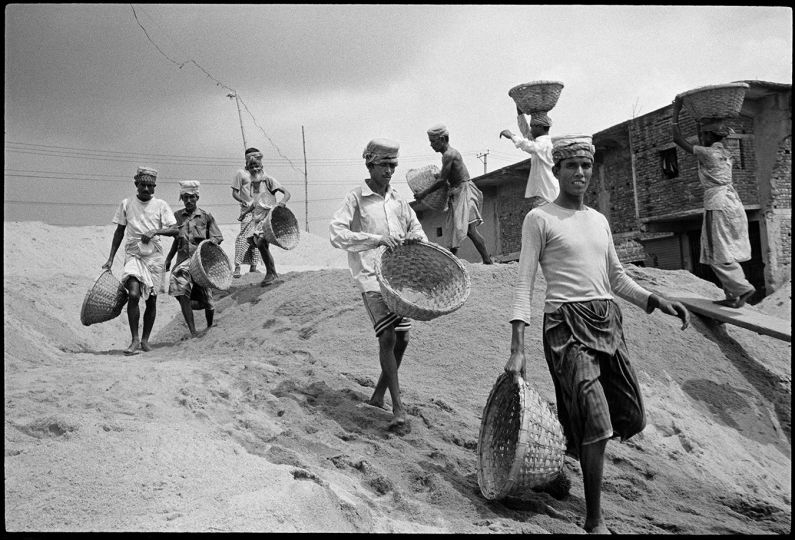

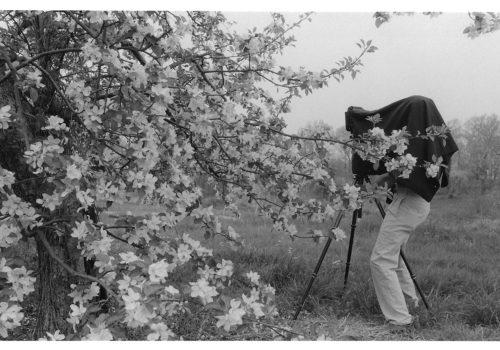

In the late nineteenth century, nearly fifty years after the invention of photography, images were being produced in industrialized countries at an exponential rate. While the practice of photography was made more popular with the introduction of dry plates and film, new methods of photomechanical reproduction made it possible to print multiple illustrations at low cost in an ever-growing number of newspapers and magazines. Historians must take stock today of this sudden explosion of images and understand its significance for, and impact on, our societies. There are a number of factors to consider, including the spread of amateur photography, the development of the illustrated press, the symbolic constructions underlying identity, history, and the idea of the faraway, as well as the burgeoning of social sciences, fostered in many areas by the advent of photography. The rise of a new regime of photo profusion, however, has also had strong implications for heritage institutions, museums, archives, and libraries, as well as for the methods of collecting images, all of which had been witnessed a sea change.

While, in the first decades, photography might have been confined to a frame, a wall panel, an album, or an atlas, its proliferation quickly raised the question of larger containers, necessarily distinct from the accumulation model represented by books and works of art. More specifically, at the turn of the twentieth century, it ushered a new type of collection: what came to be known as “museums of documentary photography,” which aimed precisely at classifying and making sense of the abundant and chaotic production of images.

Starting in the late nineteenth century, special-interest clubs and journals championed the idea of collectively exploiting photography’s documentary capacities. Across Great Britain, France, Germany, as well as in Switzerland, Italy, Poland, Russia, and the United States, amateur associations launched photography campaigns aimed at cataloging, promote, and preserve historical heritage and local traditions through images. The collective enthusiasm for documentary production generated a demand for structures capable of absorbing and channeling this unprecedented flux of images, of archiving them, and making sense of the visible through systematic curation of photographs. Thanks to a series of recent research projects conducted in various countries, we are rediscovering the rich history of these institutions, from the Record and Survey Movement initiated by the British photographer William Jerome Harrison in 1885, to the first (and last) International Congress of Photo-documentation in Marseille in 1906. By bringing together several of these studies, the themed section of the current issue intends to reconstruct the development of museums of documentary photography and related visual collections in a transnational perspective.

The generic term “photographs” used in the title covers a wide range of objects. Collections may include various types of photographs; glass, film, and paper negatives; prints on a variety of media; lantern slides; Autochromes; as well as postcards and clippings from illustrated magazines—a printed format which, far from being secondary, makes up the bulk of some collections, such as Paul Otlet and Ernest Potter’s Universal Iconographic Repertory. After all, museums of documentary photography intended to showcase the medium in all its diversity, even if the panoply of materials, formats, and cultural associations were to stand in the way of their institutional recognition.

While the apparent homogeneity of the Autochrome collection at the Archives de la Planète has contributed to ensuring the continuity and development of the museum as a whole, the heterogeneity of the media collected in Paris, Brussels, Geneva, and Lausanne has only perpetuated the uncertain status of photography in the archives of heritage institutions, and art museums more specifically.

The history of these collections is often a story of failed attempts whose record is incomplete and whose traces are fragmentary. Nevertheless, it is our claim that such projects represent a foundational moment in the history of photography. While a second wave of “photography museums” in the late twentieth century promoted, similar to art museums, the rare object and the exceptional image, and tended to privilege gelatin silver print over any other medium, museums of documentary photography directly embraced the prolific and varied nature of photography along with its indeterminate status. Well before the idea of a photo library (iconothèque or photothèque) became popular—the category gained currency only in the interwar period—followed by “image banks”—which, by promoting the concept of photographic collection as an economic resource only furthered the homogenization of images, now treated as legal tender—these museums constituted the first attempt at building heritage structures capable of accommodating photography in its plurality. Their intention was to make sense of the plenitude by organizing it, rather than repressing it or filtering it.

Estelle Sohier, Olivier Lugon, and Anne Lacoste

Estelle Sohier, Olivier Lugon, and Anne Lacoste are historians and university professors in Paris, France. This text appeared in the first issue of Transbordeur.

Transbordeur—Photographie, histoire, société

Issue 1: Themed section: “Musées de photographies documentaires”

Edited by Estelle Sohier, Olivier Lugon, and Anne Lacoste

Published by Éditions Macula

236 pp.

€29.00