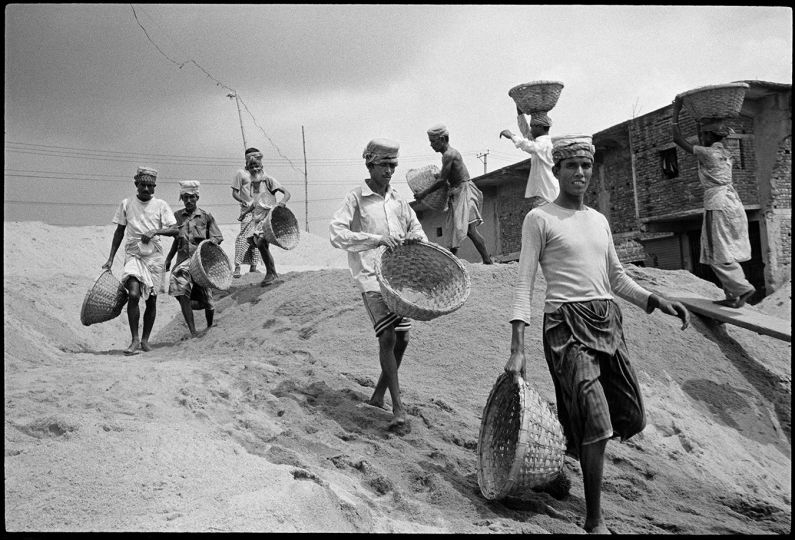

In 1920, the Spitsbergen Treaty recognized the sovereignty of Norway over the Arctic Archipelago of Svalbard under the following conditions: that it remain entirely demilitarized, exempt from taxation, environmentally intact, and open to business development from the citizens of all signatory countries. Russia, which ratified the treaty in 1935, is currently the only foreign country to make use of this right through coal mining. this is an exclusively geopolitical decision, since every Russian mine on the archipelago—Barentsburg, Pyramiden, Grumant and Colesbukta—has always operated at a loss. Barentsburg served as an observation outpost during World War II and the Cold War, as well as a potential military staging area for the Soviet Union. today, the Russian interest in Svalbard is due to the strategic location of Barentsburg given the new routes opening as a result of disappearing arctic sea ice. While the mine remains the official justification for Russian presence in the region, no one is fooled, least of all the miners themselves, who bide their time in the polar night, craving entertainment between shifts in a squalid mine.

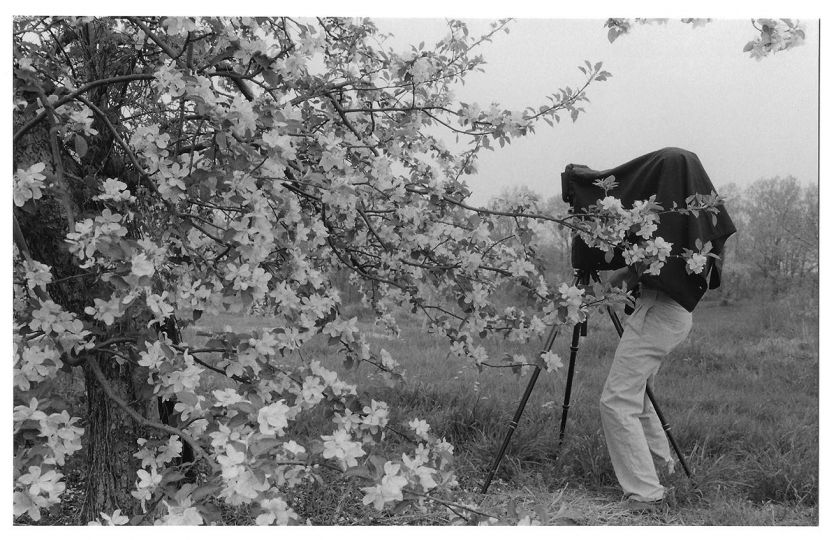

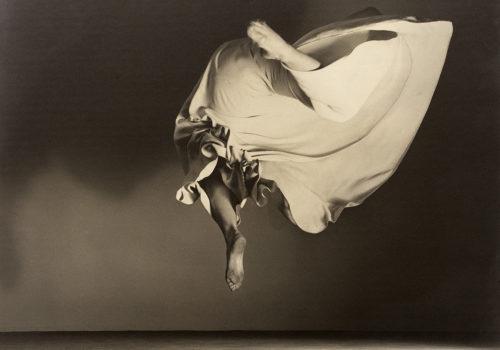

In the soviet era, however, Barentsburg and Pyramiden were popular destinations for miners, and while working there may not have been a privilege, it was hardly a punishment. the miners and other employees of these settlements were recruited for their technical skills as well as for some indefinable quality they could offer to their fellow citizens. singers, athletes and artists were especially sought after to help bring life to these isolated communities, strengthen social bonds and fend off boredom, loneliness and the sense of distance from families on the mainland.

Barentsburg and Pyramiden, company settlements without an indigenous population, once enjoyed full employment. for economic and political reasons, the Soviet Union also decided to outlaw cash rather than use the only official currency of Svalbard, the Norwegian krone. it was a land without unemployment or money. Healthcare was free, along with entertainment and food, thanks to a local greenhouse and farm. the Russian enclaves of Svalbard were perhaps the only total and uncompromised instances of soviet utopian ideals put into practice, a feat whose success demanded the autarkic conditions of the far north.

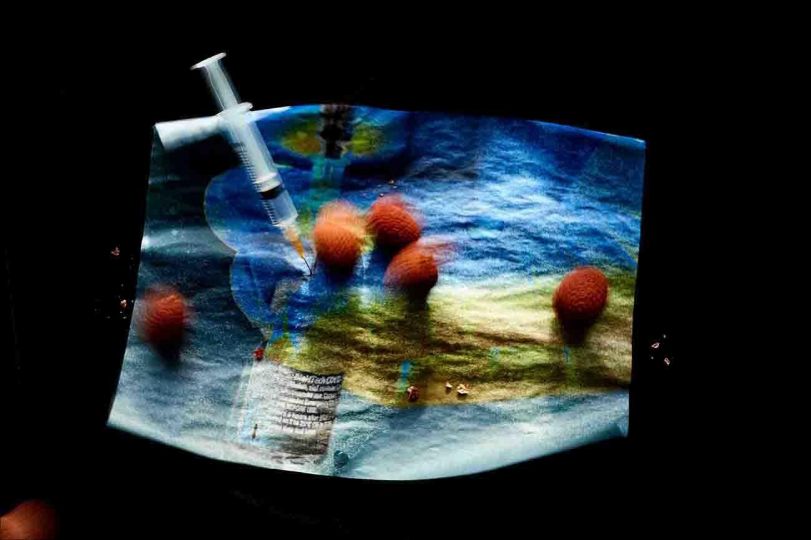

But this realization of the soviet dream could not survive the fall of the communist regime. the Russian mines closed one after the other, with the temporary exception of Barentsburg, whose resources will be depleted in a few decades. Moreover, in an attempt to minimize losses, the state-owned trust that oversees the mine, Arktikugol (literally, “Arctic coal” in Russian) is turning its focus to tourism. Renovations began in 2010, and 2013 saw the opening of a brewery, restaurant, youth hostel and a center for expeditions, all proof of a renewed interest in Svalbard by Russian authorities and the region’s growing appeal to tourists. With their statues of Lenin, aging infrastructure and abandoned buildings, Barentsburg and Pyramiden now seem merely ruins of the soviet era, but they are destined to play a part in resurgent Russian power for years to come.

Léo Delafontaine

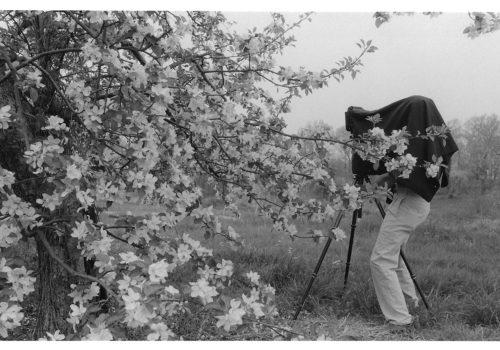

Léo Delafontaine, Arktikugol

Published by Editions 77

40€