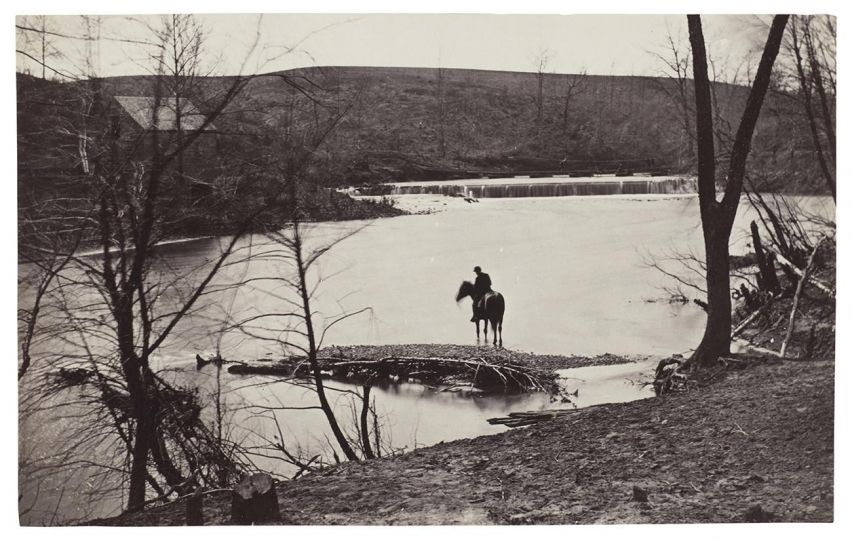

Désamour Fares, 28, is one of the five or six buyers who deal with Haiti’s only gold miners. He comes every Thursday to Lakwev, one of the three “wild” mines in the country’s northeast—the most profitable, he says. In the shade of a wood and sheet metal shed, he has been waiting for over an hour in the village, which seems to ignore him as it carries on with its hard labor. Three men operate a hoist, drawing clay from the depths of the mine. Women, marching single file, carry sacks of dirt on their heads down to the river to decant the gold.

Désamour is waiting for his turn. “They always come in the end,” he says. “They need the money.” His hand rests on his backpack, which he has placed, for safety reasons, across his knees. It carries his vagabond trader kit: a scale, an empty tube of aspirin to store the gold, and a wad of gourdes, the Haitian currency. Pierre-Silia Bastien, 47, is the first to approach this makeshift trading post. Walking slowly, she appears frail in her oversized fatigues: black shorts, a faded t-shirt and a scarf covering her hair, the only feminine article of clothing on her body. With her burnished hand, she places a few grains of gold on a piece of cardboard, making sure that nothing remains stuck to her palm; even the dust adds up on the scale. The dial settles on .9 grams. She receives 900 gourdes, about 17 euros. The buyer’s fixed rate is roughly 50% of the global standard. In Lakwev, the word “precious” evokes hope and misery, toil and wages.

Pierre-Silia is married to Jean Arnolt, the head of the community. This status confers no privileges. When she is not digging for clay in the bowels of the earth, she grows corn. “The mine is no place for women, but there’s no other way to meet our needs. It’s dark down there and a little scary, but I put the money I earn aside to pay for my children’s education.” The Creole word for children is timoun. Pierre-Silia has ten. One of them, a teenager, speaks perfect French. He dreams of being a diplomat, perhaps an ambassador.

“I don’t want them to mine for gold,” says his mother with wistful pride. “This isn’t a real job.” The future is grim, too, with resources running low. The miners have to dig deeper to extract more and more earth that yields less and less gold. “Before, you barely had to dig to find gold nuggets,” says Pierre Joseph, sitting on the edge of his mine. “Now we have to take more risks for just a few specks. Last month, a tunnel collapsed on one of the men from the village. We had to amputate his leg. I can barely take care of my seven children, and we can only dream of getting aid from the state.”

In fact, the Lakwev mine is illegal. Situated on a plateau two hours from Ouanaminthe, this hamlet resembles a sienna-colored battlefield. In 30 years, the villagers have dug over 3,000 holes separated by just a few meters. Only six are still active, but another one is being dug. Dominique Boisson, a geology professor at the State University of Haiti who has taken samples of the area, is not surprised by the shortage that now threatens Lakwev. “The site is not a source of gold. All they are finding is gold residue, which runs out very quickly.” Boisson has been tracking the source for 15 years on behalf of Eurasian Minerals, a Canadian mining company, which has surveyed northern Haiti extensively.

Surprising as it may seem, this “cursed country,” ranked by the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) as one of the top 20 least developed countries in the world, is also one of the richest in gold, which the UNDP discovered in 1972 during a soil analysis. Today, some politicians have suggested a potential 15 billion dollars in profits, a figure that has caught the attention of international companies.

“The UNDP identified two deposits: Morne Bossa and Grand Bois,” says Dannel Bélizaire, president of Géominérale d’Haiti. Bélizaire has a twinkle in his eye and the portly bearing of the Port-au-Prince bourgeoisie. Saint-Victor Saint-Juste, an elder in the mountainside village of Beaugé in the heart of the Grand Bois sector, remembers when Bélizaire paid them a visit in the late 1980s. “He came to buy land from farmers on behalf of the Canadian company Sainte-Geneviève,” says Saint-Juste. “One of my cousins sold our family land without telling me. I lost so much.” More importantly, he earned nothing.

But Saint-Juste, 81, doesn’t want to cause a fuss. Wearing a straw hat, he preaches peace with it comes to dealing with the companies operating in the area. “Fifteen years later, Dominique Boisson came up here, showing us papers signed by Bélizaire. What we sold him now belongs to Eurasian Minerals.” On a table in his hut, Saint-Juste spreads out a lifetime of paperwork. Among the papers is a contract signed by Eurasian Minerals and Newmont Mining, the world’s second largest mining company. The contract, written in Creole, stipulates that Saint-Juste has the right to cultivate the land, which now belongs to the joint venture of the two companies. The day they decide to take over, Saint-Juste will be forced to leave and compensated with an unspecified amount of miney. At the bottom of one of the legal forms, the old man had used his fingerprint as a signature. “I don’t know how to read,” he confessed.

The fate of communities like Beaugé has some groups worried, and they have been working to help the citizens exercise their rights. “They won’t know how to defend themselves against the power of Western groups,” says Ellie Happel, a lawyer for the Global Justice Clinic, a Haitian program. “For these communities who live off what nature provides them, the opening of a mine could have terrible consequences.” In 2010, when Eurasian Minerals returned to Beaugé, the company invested 8 million euros in research, setting up a camp of 200 people and building infrastructure for its engineering. Saint-Juste, and the entire village, worked for the operation. “I looked after the motor of the drill. When they found gold, I wanted to keep some of it, but they told me I wouldn’t know what to do with it,” he says, laughing.

“Dominique Boisson’s company paid us 225 gourdes [4 euros] a day, and he paid us 3500 euros to dig a trench in our field. That’s a lot of money! The white men filled it in before they left, and we heard nothing more about it.” Saint-Fort Dufresne sees things differently. “Not everyone worked the same job. I was tasked with redoing the village road and digging in the trench. Other people were securing the drill site. I couldn’t even walk on my own land! Look, we’re surrounded by vegetation off which we live. I don’t want to trade it for work in a mine.”

Following the 2010 earthquake, Haiti received considerable support from Western backers. With the new political stability, the country became even more attractive to investors, to the extent that, in 2013, Parliament called for a moratorium on such activities, which drew attention to outdated legislation and 20% of the territory acquired through prospecting. The Minister of Finance and Public Works teamed up with the World Bank to draft a new law. The bank advised the government to organize a wide-ranging consultation process with the involvement of the International Monetary Fund and the adviser John Williams, who wrote the law in consultation with the interested companies. At the same time, it invested 4.4 million euros in the Eurasian Minerals business in Haiti.

“The August 2014 bill contains many innovations […]. For example, it provides a new and clear framework for artisanal mining,” says Chrystelle Chapoy, a spokesperson for the World Bank.

All the major industry players insist that they are working for the good of the country’s future. “In addition to the royalties, the taxes on income, and the employment it affords the population, think of the infrastructure this could bring us! Look at our neighbors, the Dominicans. I think they were able to develop their tourism industry so well because they also developed their mines,” says Dominique Boisson. For the past 15 years, the Pueblo Viejo mines have been operating right across the border. It lies on the same “mineral belt” that runs through both countries. Nearly 6 million ounces have been mined, out of a potential 25 million, an encouraging figure for those who believe that the key to Haiti’s future can be found beneath its feet.

Back in Lakwev, in the river where the loot is separated from the mud, Rosaline replaces the headscarf that protects her from the blazing sun. She has a big smile on her face, wading through the mud with the other women from the village. When she isn’t in school, this 16-year old, who dreams of becoming a doctor, saves what money she can and takes care of her little sister, walking her to class every day. The journey is eight hours round-trip.

INFORMATIONS

URL: http://l-instant.parismatch.com

FB: https://www.facebook.com/instant.parismatch

TW: https://twitter.com/instantmatch

Instagram: http://instagram.com/l_instant_parismatch

L’Œil de la Photographie is partner of L’Instant Paris Match.